“God saves me by giving me the spirit to bear it”: A bishop who endured more than 300 lashes during WWII

A/Prof Joseph Thambiah // November 15, 2019, 4:57 pm

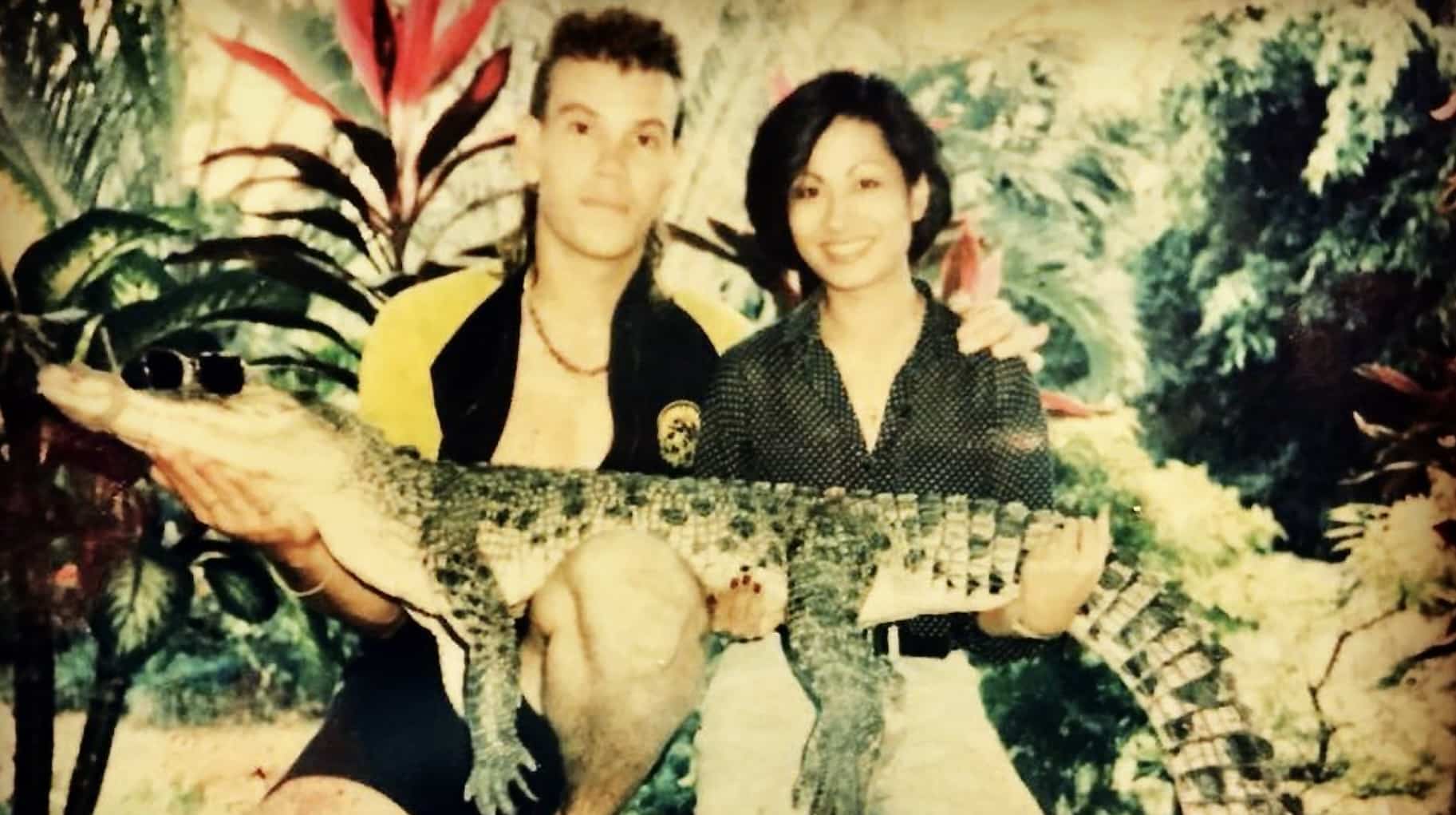

Bishop Leonard John Wilson (left) and Reverend John Hayter sharing a light moment after the war. Photo courtesy of St Andrew's Cathedral.

John Leonard Wilson had been the Archdeacon of Hong Kong and the Dean of St John’s Cathedral there from 1938 to 1941. On 22 July 1941, he was consecrated Bishop of Singapore in St John’s Cathedral.

He left hurriedly for Singapore to assume his post just four months before the Japanese invasion.

In the difficult days that followed the outbreak of war, Bishop Wilson demonstrated great courage and resolve by continuing services throughout, and once even clearing the Nave of its pews so that the Cathedral could be used as a hospital for the war wounded.

He even cleared the Nave of its pews so that the Cathedral could be used as a hospital for the war wounded.

He managed, by the grace of God and sheer force of will, to convince the Japanese authorities that the work of the Church constituted an essential service. By so doing, he temporarily secured freedom for himself, Reverend Reginald Keith Sorby Adams and Reverend John Hayter.

With Revd Dr D D Chelliah and Lieutenant Andrew Ogawa, he was instrumental in the creation of the Federation of Churches, which brought together all the non-Roman Catholic denominations. Interdenominational services were frequently held not only in the Cathedral, but also in the major churches of other denominations. Shortly before his internment, the Japanese authorities closed the Federation of Churches.

Sourcing for money

The plight of those interned in Changi soon became clear to him. Many were brought into hospitals in town, starving and sick. He felt that with some money made available to these prisoners, they might be able to purchase some essential foodstuffs. And so the Bishop went sourcing for money, first from the Japanese, then the local banks and finally the International Red Cross.

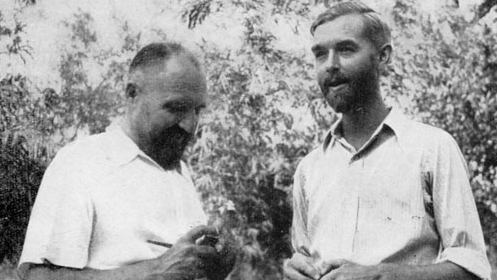

Bishop Wilson (left) returned to Singapore in 1969 to participate in a BBC documentary entitled “Return to Hell”. He was reunited with his old friend, Andrew Ogawa. Source: The Straits Times, Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

None of them were allowed by the authorities to lend any money to prisoners of war or internees, so he borrowed it on behalf of the Anglican Church. He told the lenders that the Anglican Church had outlasted many empires, and that it did not matter who the victor of this war was – for they could be assured that the Church of God would go on, and their money would be safe.

He told the lenders that the Anglican Church had outlasted many empires.

Through his efforts, large amounts of money were channelled into Changi. The transfer of money was done through patients, who were returning to Changi Prison from Miyako Hospital. The work was usually done through Choy Koon Heng and his wife Elizabeth.

Bishop Wilson appeared to be fearless and always ready to come to the aid of others. George Daniel, a member of the Cathedral choir then, recalled: “The Bishop was always a tower of strength to us. He was always ready to risk danger to look after us.”

One Sunday morning, a Japanese soldier stopped a choir girl on the private road inside the Cathedral precincts as she was coming to a service and insisted on her bowing to him in the Japanese way. When the Bishop, who was in the vestry, heard of the incident, he immediately went out to demand an explanation!

Horrific torture

After about a year of parole, Bishop Wilson was interned in Changi Prison in March 1943, together with the other clergy. Despite this, he continued to minister to the spiritual needs of his fellow prisoners. He organised and chaired a committee to look after the welfare of his fellow prisoners of war.

The relative peace did not last for long. Following the infamous Double Tenth incident of October 10, 1943, he was singled out for interrogation and tortured at the Kempeitai’s headquarters in the YMCA Building. Revd Hayter provides a glimpse into the horrific nature of Bishop Wilson’s torture:

Artist’s impression of Bishop Wilson’s position during his torture by the Kempeitai, based on a description provided by Bishop Wilson to Revd John Hayter. Illustration courtesy of Don Low.

“On the following morning, he was again taken to the torture room, where he was made to kneel down. A three-angle bar was placed behind his knees. He was then forced to sit back on his haunches. His hands were tied behind his back and pulled up to a position between his shoulder blades. His head was forced down and he remained in this position for seven and a half hours.

“After my first beating I was almost afraid to pray for courage lest I should have another opportunity of exercising it.”

“Any attempt to ease the strain of the cramp in his legs was frustrated by the guards who brought the flat of their boots down hard on his thighs. At intervals, the bar behind his knees was twisted or the guards would jump on one or both of the projecting ends … He said afterwards that this was the one time that he lost his nerve and pleaded for death.

“Again the next morning, the Bishop was brought up from the cells, this time to be tied face upwards to a table, with his head hanging over its end. For several hours, he remained in that position while relays of soldiers beat him systematically from the ankles to the thighs with three-fold knotted ropes. He fainted, was revived with warm milk and the beating continued.

“He estimated that he must have received over three hundred lashes … It was not long before he lost sense of feeling. The blows had lost their power to hurt, so dead were the nerves in his body … Finally, he was taken down to the cells and thrown onto the floor. There was no skin left on the front of his legs from the thigh downwards. His flesh was raw and livid from the blows he had received, torn to shreds …”

Praying for courage

In a broadcast sermon he gave in 1946, Bishop Wilson recounted:

“I remember Archbishop Temple in one of his books writing that if we pray for any particular virtue, whether it be patience or courage or love, one of the answers that God gives to us is an opportunity for expressing that virtue.

“After my first beating I was almost afraid to pray for courage lest I should have another opportunity of exercising it, but my unspoken prayer was there, and without God’s help I doubt whether I should have come through. Long hours of ignoble pain were a severe test.

Reunion between Bishop Wilson and war heroine Elizabeth Choy in 1969. That same year, he retired to Yorkshire. Bishop Wilson died of a stroke on 22 July 1970. Source: The Straits Times, Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

“In the middle of that torture they asked me if I still believed in God. When by God’s help I said, ‘I do,’ they asked me why God did not save me, and by the help of His Holy Spirit I said, ‘God does save me. He does not save me by freeing me from pain or punishment, but He saves me by giving me the spirit to bear it,’ and when they asked me why I did not curse them I told them that it was because I was a follower of Jesus Christ, who taught us that we were all brethren.”

“In the middle of that torture they asked me if I still believed in God.”

In spite of the suffering and pain that he was undergoing, Bishop Wilson’s thoughts were on his fellow sufferers. Towards the later part of their imprisonment in the YMCA, the prisoners were allowed some physical exercise. One of them would have to take the drill and count out: “Ichi, ni, san, shi.” (“One, two, three, four,” in Japanese.) Bishop Wilson would shout out in English instead: “Be of good cheer; lift up your hearts!” to the same timing! Hearing those words in those crowded and foul-smelling cells spiritually uplifted the prisoners.

Baptism in jail

The remarkably high courage and Christian fortitude demonstrated by the Bishop impressed his non-Christian fellow sufferers so much that one of them, a Chinese named Lam Mau Fatt, desired to become a Christian. After secret instruction during the silent hours of the night (detection of communication of any sort between prisoners meant more torture), the Bishop baptised him with water from the commode, the only water available in the cell.

Elizabeth Choy recounted in an interview given in the 1960s that Bishop Wilson “was whipped with wet ropes and tortured so badly that he became unconscious and his body became swollen”.

“For days he could not eat and the bruises made his whole body look blue and black, yet he did not curse his torturers.”

“For days he could not eat and the bruises made his whole body look blue and black, yet he did not curse his torturers. On the other hand, he prayed for them and when Singapore was liberated by the British, some of his torturers came to him to be baptised.”

Throughout that dreary and desolate period, he held tightly on to God. He later recalled how God revealed Himself even in the presence of pure evil:

“I was in a crowded filthy cell with hardly any power to move because of my wounds, but here again I was helped tremendously by God. There was a tiny window at the back of the cell, and through the bars I could hear the song of the golden oriole.

“I could see the glorious red of the flame of the forest tree, and something of God’s indestructible beauty was conveyed to my tortured mind. Behind the flame trees I glimpsed the top of Wesley’s church and was so grateful the church had preserved so many of Wesley’s hymns. One that I said every morning was ‘Christ Whose Glory Fills the Skies’.”

Into the sunlight

After suffering eight months of this torture, Bishop Wilson was released to return to internment in Changi Prison. He recalled vividly the first moments after his release:

“God in all His power and strength and comfort is available to every one of us today.”

“After eight months I was released and for the first time got into the sunlight. I have never known such joy. It seemed like a foretaste of the Resurrection. For months afterwards I felt at peace with the universe, although I was still interned and I had to learn the lesson or the discipline of joy. How easy it is to forget God and all His benefits.

“I had known Him in a deeper way than I could ever have imagined, but God is to be found in the Resurrection as well as in the Cross, and it is the Resurrection that has the final word. God in all His power and strength and comfort is available to every one of us today.

“He was revealed to me, not because I was a special person, but because I was willing in faith to accept what God gave.

This story is an excerpt from the book, The History of Anglicanism in Singapore, 1819 to 2019: The Bicentenary of Divine Providence by Armour Publishing Pte Ltd. It is reprinted with permission.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light