Jason Wong: In prison but not imprisoned

This National Day Week, Salt&Light brings you stories of extraordinary faith among Singaporeans both at home and abroad.

Jason Wong // August 6, 2018, 2:47 pm

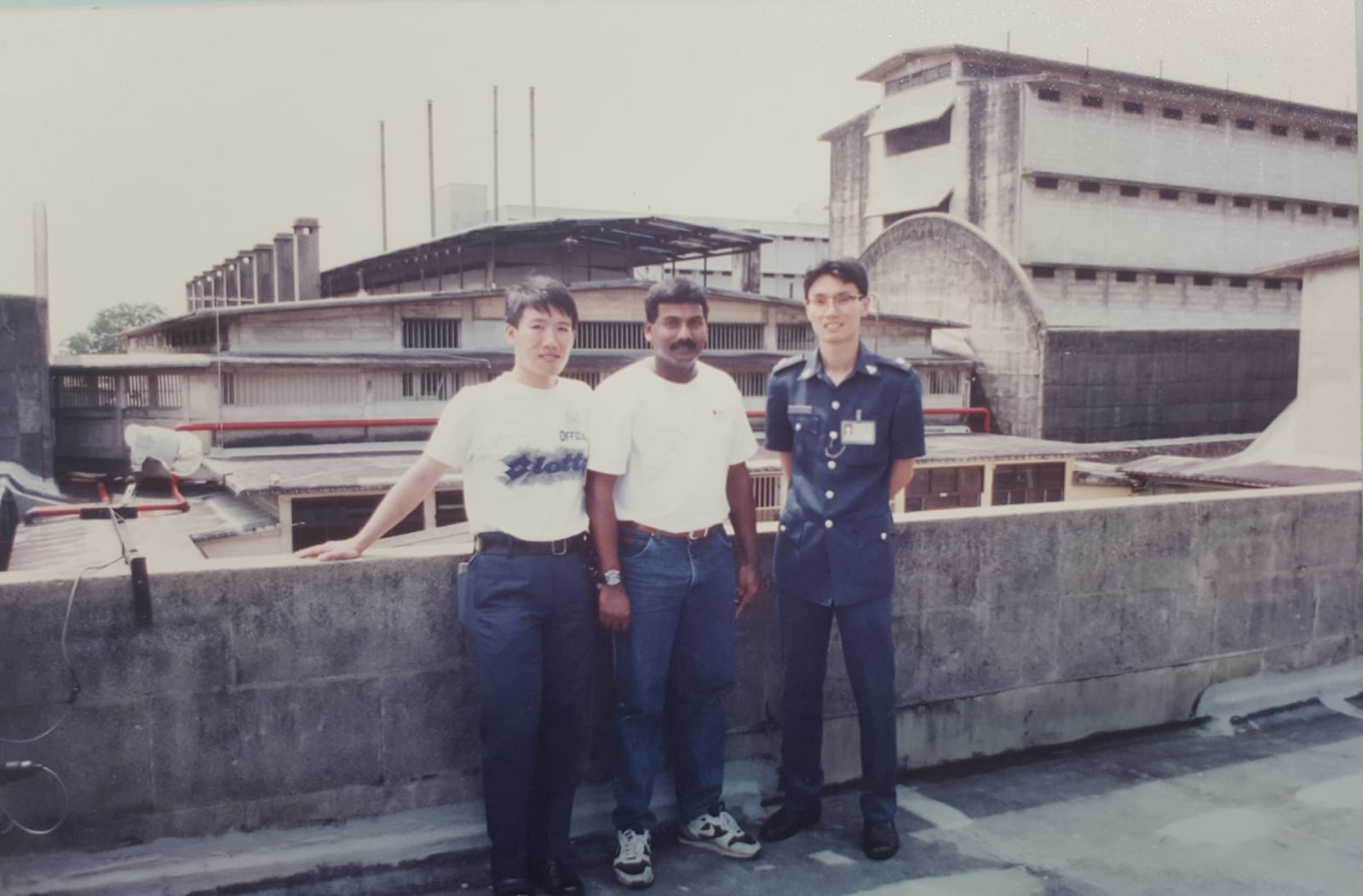

Jason Wong (far right) at Changi Prison with colleagues.

I started my career with the Singapore Prison Service (SPS) in 1990, and served there for 17 years. I documented many of my learning during those years.

I would like to share the following extract from my book Trash of Society on the early years of my career in SPS and how my eyes were opened.

Changi Prison

After the month-long orientation, I was deployed to work. The year was 1990. I was first posted to the former Changi Prison, designed for 1,600 inmates but housing 2,400 at that time.

Instead of one inmate per cell, some cells were holding three or four inmates each. I learnt early that SPS never assigned two inmates to a cell because in the event that something happened, it would be one person’s word against another.

Three would be better as the third person can act as a witness. Besides, two can easily conspire to commit some illicit activity. It would be harder for three to collude.

Not only was overcrowding severe in those days, staff shortage was significant, as being a prison officer was not exactly an attractive prospect.

Prison conditions were spartan for both the inmates and the staff. Staff rest areas and dining areas were indiscernible from the inmate areas.

To survive the shift, prison officers must be mentally prepared to be locked up in a humid and confined space for hours on end. The words of my professor of economics returned: “Go to a place where no one wants to go.”

Well, here I am.

No coincidences

I believe my deployment at Changi Prison was no coincidence.

One of my burning questions was how to be a good prison officer. More precisely, “How to be an exemplary Christian prison officer?”

This was not something I could glean from the Bible.

My observations of the more experienced officers told me that many perceived this as simply a job. I was looking for someone who regarded this as a calling.

Most of them advised: “Don’t talk to the prisoners too much – they will take advantage of you.”

“Be careful of that Housing Block – they are the hard-core gangsters.”

“Drug addicts have the worst attitude and behaviour – they don’t realise the harm they have inflicted on society, so they don’t think they deserve to be locked up.”

I was looking for a prison officer to show me how to reach out and soften their hearts.

“You need to look tough. If you show them your fear, they will devour you.”

“This is not Orchard Road – this is not a safe place. Watch your back.”

“It is us against them and we must always win. We cannot afford to lose.”

This was how new officers were inducted to survive the harsh prison environment, especially in a maximum-security prison like Changi Prison.

The veterans meant well – they wanted to pass on their wisdom to rookies like me.

I was a scholar from a learned institution, with no experience surviving the institution of crime and gangs. I may be smart, but a prison officer needs to be street smart to outsmart the inmates. Naivety and gullibility have no place in a prison.

“I am paid by the government to do God’s work.”

The culture was about us versus them, power and control, prison officers talking down to prisoners playing hide-and-seek with them, police-and-thief, and gang sub-culture.

Just when I thought this was bleak, I was told things were far worse before. But should we be satisfied with the status quo, even if it were an improvement from the past?

Something inside of me felt we could perceive the prisoners differently and run the prison in a better way.

Therefore, I was looking for a prison officer to show me the ropes differently – teach me how to help the inmates and make a difference in their lives; show me how to reach out and soften their hearts.

The Prison Chaplain

If God calls, He will provide. If He assigns me a task, He will equip me to accomplish it.

I learnt to be a different prison officer – a Christian prison officer – from the late Rev Henry Khoo, Head of the Prison Education Unit who was double-hatting and volunteering as the Prison Chaplain.

I will always remember his words to me shortly after we met: “Jason, I am paid by the government to do God’s work.”

As Head of the Prison Education Unit, he oversaw a group of teachers seconded from the Ministry of Education, as well as academic education programmes administered in Changi Prison and several other penal institutions.

Paid as a civil servant, he was also appointed as the Prison Chaplain. Somehow, he was able to integrate his secular work with his Christian ministry. Due to teacher shortage, he would also conduct some lessons. Although he did not overtly mention Jesus or refer to the Bible outside of Bible classes, every prisoner could see Jesus in him.

If I walked into Halls (now called housing units) where prisoners were accommodated, I would witness their contrasting reactions to the Superintendent and the Prison Chaplain.

Even the most notorious secret society leaders and hardcore gangsters would address him with big smiles.

The former got the cold shoulder from the inmates, even if their greeting was in unison – “Gooooood moorrrnnniiiiingg, SIRRR!” – it was done out of duty and obligation, not from the heart.

With Rev Henry Khoo, even the most notorious secret society leaders and hardcore gangsters would address him with big smiles.

The contrast was stark. The Superintendent would say to me as we passed the cells: “Don’t trust him”; “That inmate is very notorious”; “We are watching this one very closely”, while Rev Henry would say: “This inmate has accepted Jesus”; “That inmate leads worship in the chapel”; “He has started attending chapel service.”

Rev Henry Khoo’s interaction with the inmates, including the most fearsome hardcore ones, evoked images of Jesus in human form walking in the prisons. I whispered to God, I want to be like him.

I’m praying for you, Sir

One place within Changi Prison that Chaplain spent many hours at was the “Condemned Block”, which housed those sentenced to be hanged. His father, the late Reverend Khoo Siaw Hua, the first prison chaplain, specialised in counselling condemned prisoners who were open to Christianity.

The responsibility entails spending last hours with death row prisoners in the week of execution.

Rev Henry’s father had passed the baton to him. Initially, Rev Henry was plagued with fear: He wondered if he could follow in his father’s footsteps. He would not be effective in praying for others to receive peace if he himself was without peace. He asked God to remove the fear and give him His love to embrace this role. God answered his prayer and he could sleep soundly after the first case, and all subsequent cases.

“There is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love.” (1 John 4:18)

I no longer viewed him as a prisoner or a murderer, but a fellow brother facing the consequences of his mistake.

Within days of our first meeting, Chaplain brought me into the Condemned Block to visit his counselees.

I still remember the first condemned prisoner I met. Chaplain led me to the first cell. Behind the iron bars stood a burly figure in the single cell, his back facing us. At the sound of our footsteps nearing his cell, he turned. Immediately, he recognised Rev Henry and walked forward.

Chaplain whispered into my ears: “He killed his wife.” Before I could ask why, the murderer stood right in front us. If not for the iron bars separating us, I would not have been able to compose myself.

“Hi Rev Khoo, how have you been?”

“I am well and would like to introduce someone to you.”

At this, the prisoner who murdered his wife turned towards me and said to the Chaplain: “Oh, is this the new prison officer you told me about?”

“Yes, this is ASP Jason Wong,” Chaplain smiled.

“Good afternoon, Sir! I have been praying for you,” the prisoner beamed at me.

My tense muscles relaxed. I no longer viewed him as a prisoner or a murderer, but a fellow brother facing the consequences of his mistake.

I found out later from Chaplain that it was a crime of passion. He caught his wife in bed with another man, and lost control of himself. He had since repented and given his life to Jesus.

I never thought that after 2,000 years, Jesus is still reaching out to criminals at the very last hour: “Today, you will be with me in Paradise.” (Luke 23:43)

This facebook post was first published by Jason Wong on July 25, 2018, and is republished with permission.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light