How ex-journalist Sylvia Yu is bringing about reconciliation with heartbreaking true stories of Asia’s “comfort women”

by Janice Tai // September 9, 2022, 2:52 pm

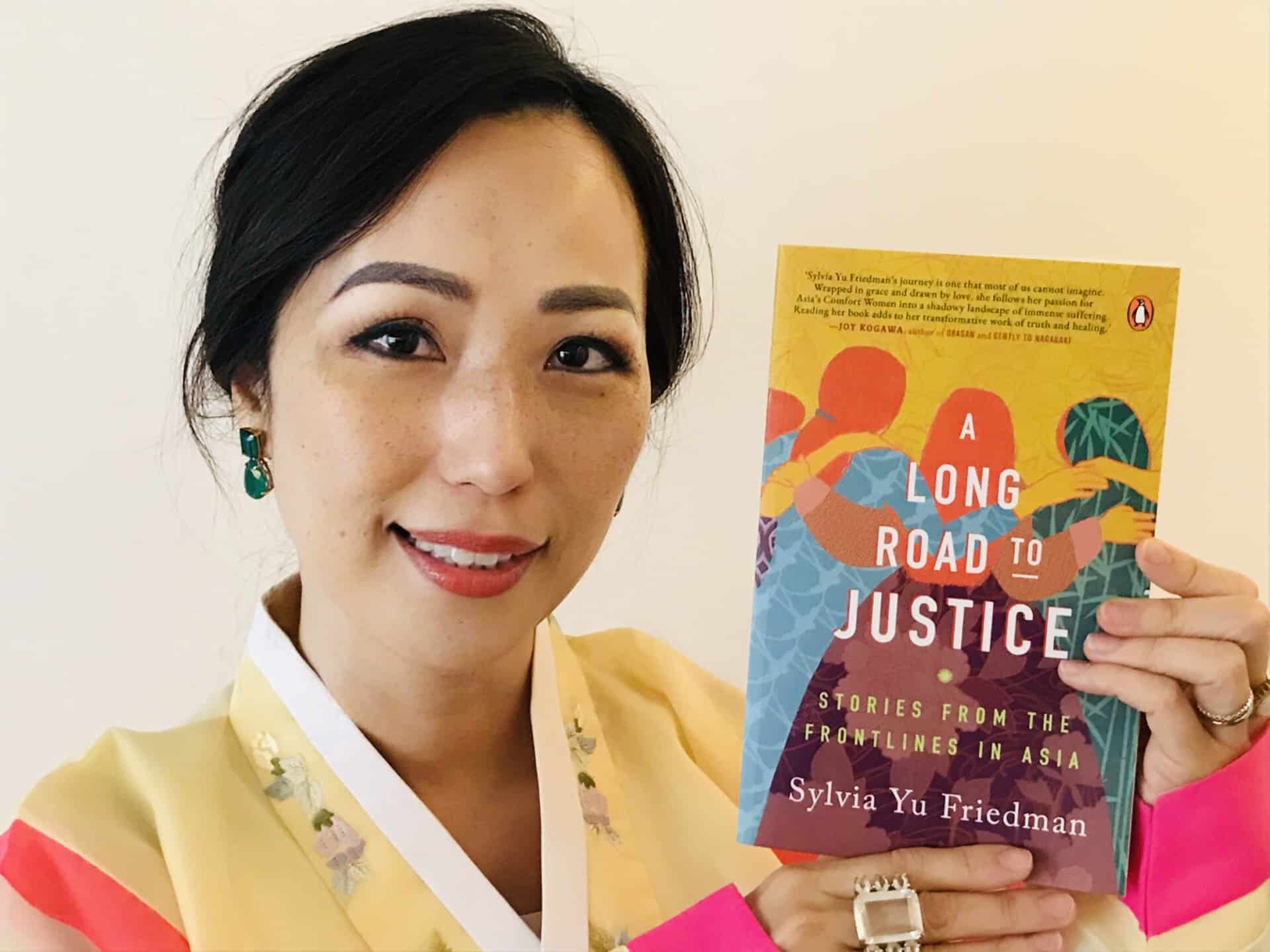

Sylvia Yu Friedman with her third book, A Long Road to Justice. She is an award-winning filmmaker, investigative journalist, speaker and advisor to philanthropists. All photos courtesy of Sylvia Yu Friedman.

As a Korean immigrant child who grew up in Vancouver, Canada, Sylvia Yu hated the Asian face that stared back at her each time she looked in the mirror.

She lived in a predominantly white neighbourhood in Burnaby and stood out as the only Asian girl in her grade. It did not help that she did not see any Asians who looked like her on television or in positions of authority, whether at school or in society.

In her teens, she felt no connection with her Korean heritage.

Sylvia demanded for her mother to speak to her only in English and never to address her by her Korean name, Saejung.

Whenever schoolmates came over to play, they looked inside her fridge and were appalled by the big jars of kimchi (Korean pickles).

“Eww, what is that?” they asked while scrunching up their noses. Sylvia burned with shame and wished she could disappear, even though kimchi was her favourite dish and their family’s mealtime staple.

One year, a few Caucasian girls in her fifth-grade class would say ‘Chink you’ instead of ‘Thank you’ to her.

So, Sylvia demanded for her mother to speak to her only in English and never to address her by her Korean name, Saejung.

Soon after, her parents divorced and her father drifted out of her life. Sylvia cried herself to sleep for a long time.

“At the time, we were one of the rare families with divorced parents, and this seemed to magnify the turmoil that I, a depressed and highly sensitive child, felt about being the only Asian in my class,” said Sylvia, who is now in her 40s.

Faith and social awakening

Even though Sylvia was brought up in the Korean church community, she often questioned her faith.

“It felt as though we were playing religion in church, but there was no heart and no God in our midst. Our Sunday school teachers looked bored themselves and lacked that infectious spirituality,” said Sylvia. Even her friends, who were mainly children of pastors and elders, were rebellious and could not be bothered with God.

Twelve-year-old Sylvia and her best friend, aged 11, paired up and went to do street evangelism in the most dangerous part of the city.

Things changed drastically a year later. One of her youth church leaders, John, experienced the fire of revival and began organising trips to do street preaching in downtown Eastside, an area filled with druggies and commonly referred to as the “poorest postal code” in Vancouver.

That was how the 12-year-old Sylvia and her best friend, aged 11, paired up and went to do street evangelism in the most dangerous part of the city without any adult supervision.

“It was a formative experience to be able to get out there and talk with strangers about my Christian faith. It opened my eyes to the spiritual needs out there and I believe a boldness grew within me from that time,” said Sylvia.

When she was 15, she went on a mission trip to Tijuana, Mexico, with her church. It was a life-transforming trip as she was not only exposed to poverty and orphans, her eyes were also opened to what God can do in missions.

“There were miracles on these trips, such as the one time when a stranger helped us with directions and then he completely vanished. The driver felt that this stranger was an angel,” said Sylvia, who would later return to Mexico five more times for missions.

While reading Religious Studies and English Literature in university, Sylvia also served as a youth pastor in a Korean Baptist Church for almost three years.

Stepping into the media sphere

Upon graduation, she got a job at a TV station and later went on to be a TV journalist and producer for PBS (Canada’s Public Broadcasting Station).

In July 2001, during her first few years in the profession, Sylvia heard that Kim Soon-duk, an 80-year-old who had been a “comfort woman” (military sex slave) during the Japanese Occupation, would be speaking at a press conference at the US State Department in Washington DC.

Kim Soon-duk had been so inspired by Kim Hak-soon, the first woman who broke the silence for “comfort women” in 1991, that she also began coming forward to testify of her past experiences.

According to historians, Japanese soldiers coerced or lured an estimated 200,000 women from Korea, China and other occupied territories into military-run rape centres in Asia and the Pacific, from the 1930s until the end of the war. It was one of history’s largest examples of state-sponsored sexual slavery, and one that political leaders in Japan denied for decades.

A “comfort station” in Shanghai, China.

At that time, Sylvia had written an article about the “comfort women” for a magazine but was not able to interview any survivors. She also could not find much information in English on the topic, other than some academic articles and United Nations reports.

“I felt that I should spontaneously drop everything and fly there for the press conference. I asked my pastor’s wife to pray with me and discern together if this was something I should do. We both felt peace about this,” said Sylvia.

The voice of Comfort Women

It was a crazy move because she would have to take a car ferry to Seattle and then fly to DC for the press conference which was taking place the very next day. She had not even booked any accommodation for that night.

Yet Sylvia remembered the vow she made nearly a decade ago when her mother handed her a newspaper article on Kim Hak-soon’s public testimony about the horrors of sexual slavery – that she would fight and do something for these women.

“I learnt that the elderly Korean woman survivor was of my age when she was forced into Japanese military sex slavery. I remember having a sinking feeling that it could have been me had I been born at that time in Korea. I also felt deep dismay that I hadn’t learnt of it in my Social Studies class at school,” said Sylvia.

The young reporter hurriedly bought her flight ticket and made a personal trip to the press conference; it was not a job assignment, though she was also planning to write about it for a magazine.

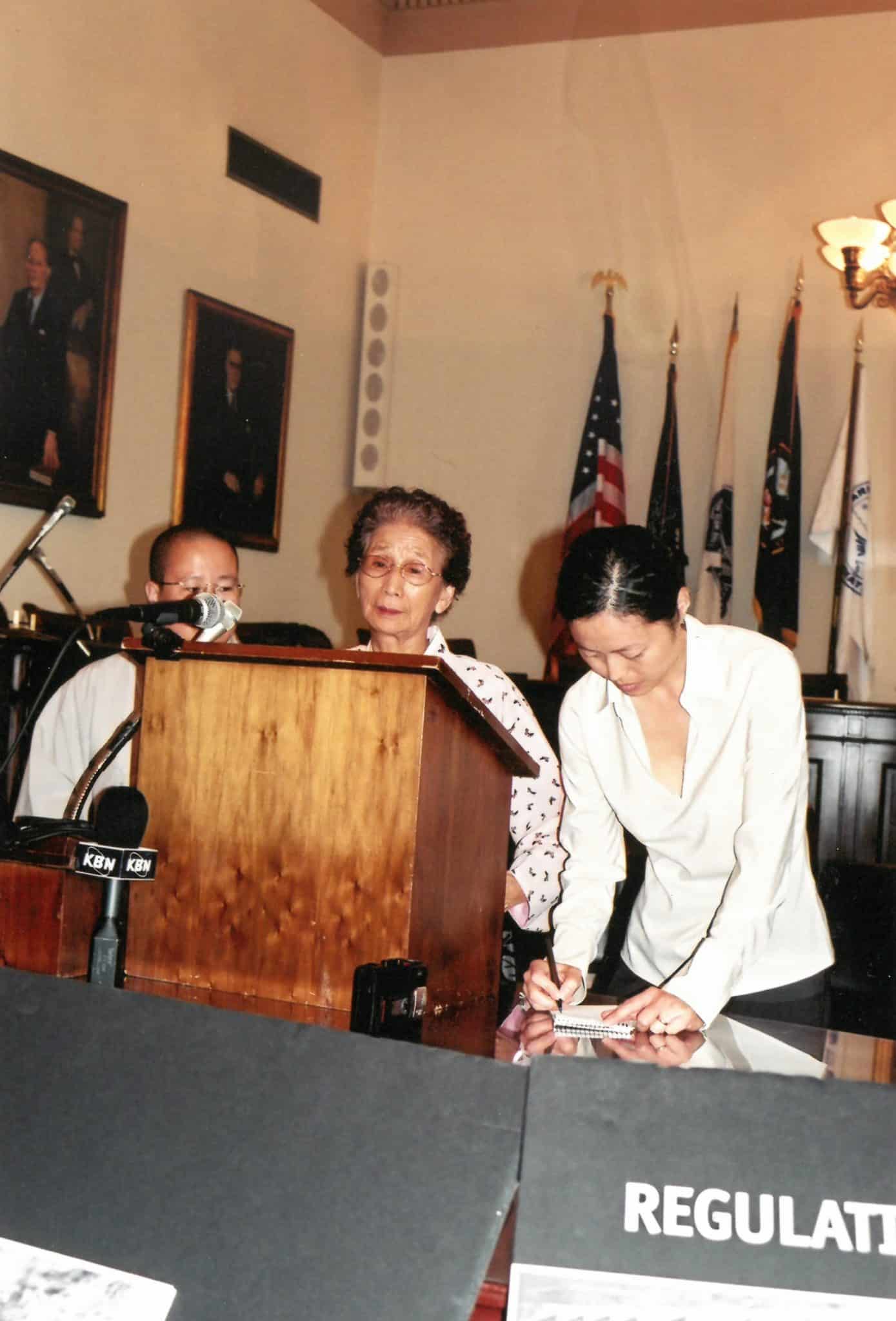

Kim Soon-duk speaking in Washington DC in 2001.

It was such a watershed meeting for her that she went on to write an opinion piece in Canada’s national newspaper, which in turn led to a leading publisher knocking on her door to get her to write a book on the topic.

“I felt God was leading me to write a book. I didn’t fully know why then but I do now – it’s part of my justice missions calling to write to raise awareness and to mobilise people to take action,” said Sylvia, who would go on to write the book Silenced No More: Voices of Comfort Women. It is the only journalistic account of Japanese military sex slavery during the Second World War.

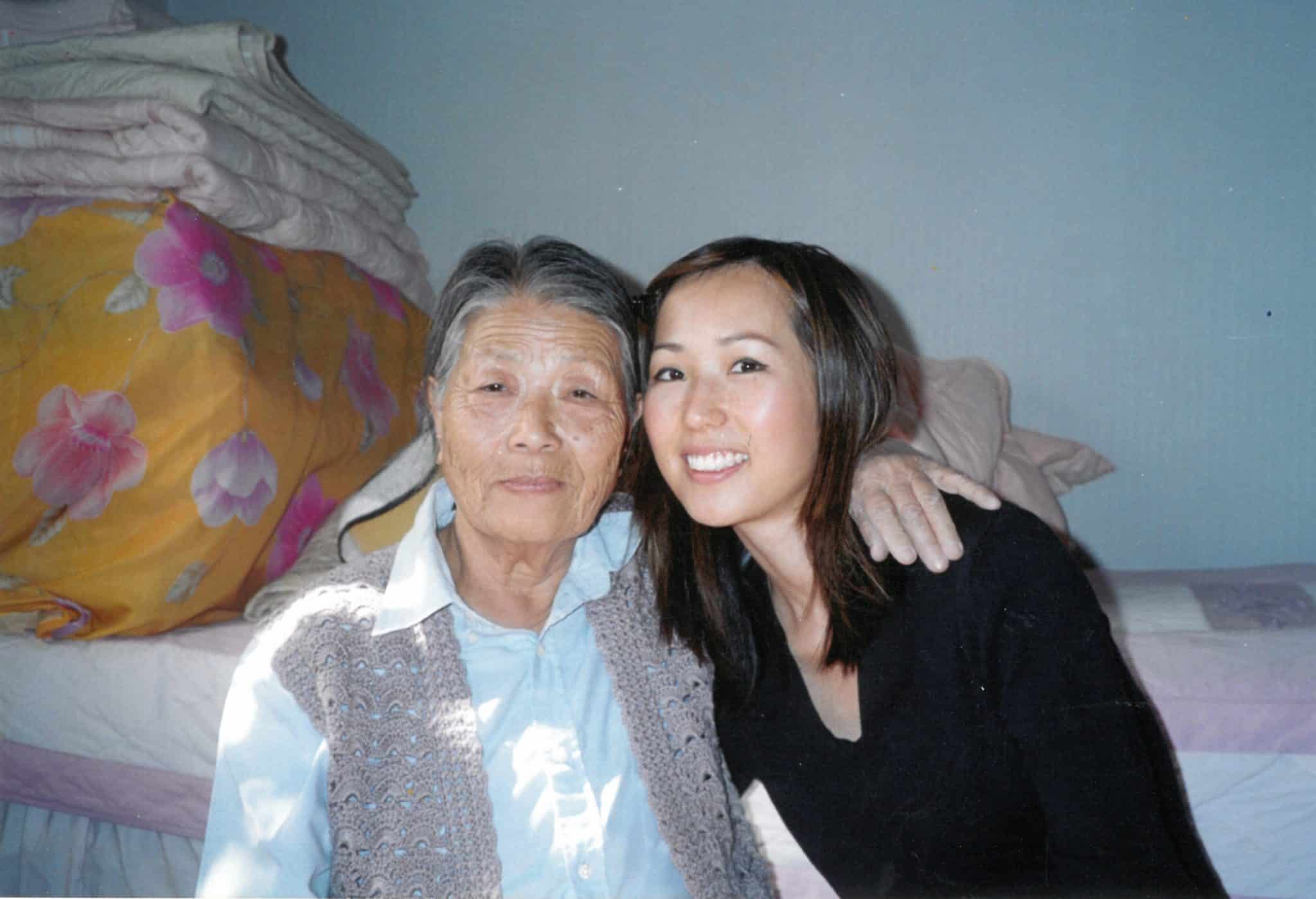

Sylvia Yu with Kim Soon-duk, one of the first few comfort women who has spoken up about her past experiences in the war.

As part of her research for the book, she travelled to many countries – the United States, China, South Korea, Japan and Hong Kong – over a span of a decade to interview survivors of Japanese military sex slavery.

“Their stories were heartbreaking and had tragic parallels to those told by the Korean women, such as being stripped of their identities and given Japanese names, being trapped in a prison at the military brothels, and experiencing long, tortuous line-ups of soldiers waiting to rape them,” said Sylvia.

Sylvia with Hwang Geum-Joo, a former comfort woman in Seoul.

“They have led me on a long road to justice – to tell the untold stories of human slavery survivors and to help bring attention, funding and change to those who are suffering,” she added.

There were many occasions during that span of 10 years when she felt like giving up on the book project.

It was depressing for her to research on and write about women being raped repeatedly and their lives destroyed by sexual violence in the war. The writing process was also prolonged because she was simultaneously working full-time and did most of the travelling needed for the interviews during her holidays, with expenses paid out of her own pocket.

Sylvia speaking at her book launch in 2015.

“There were a lot of sacrifices involved but God knows what each of us needs to finish our particular assignments in our calling journey. Along the way, the Lord sent John Dawson from Youth With A Mission (YWAM), Cindy Jacobs, Patricia King and other mighty spiritual giants to encourage me to finish the book,” said Sylvia.

“John Dawson affirmed my vision to write about the need for racial reconciliation between Chinese, Koreans and the Japanese – because there were generational war wounds from the Japanese military and the wounds of war that needed closure with a proper, healing apology from the Japanese government,” she added.

In the years while she was writing her book, Sylvia realised that she was also called to play a role in serving those in China as well as those of the Chinese diaspora.

Call to the Chinese and China

Many Chinese pastors and leaders began coming into her life, and she was commissioned to write Pastor Augustus Chao’s biography in late 2001.

Pastor Chao is considered the father of Chinese churches in Canada as he had pioneered just about every Chinese Alliance church across Canada in the 1970s and 80s. Sylvia and Pastor Chao shared a beautiful bond and the book was published a year later.

In 2004, Sylvia went on a study trip to China for her research on Japanese war crimes. When she returned to Vancouver, she could not stop crying for a week. As she prayed for the country, she saw visions of suffering people in China – the poor, the elderly and orphans – and felt a burden for them.

Sylvia in Shanghai during her first trip there in 2004.

Little did she know that she would end up moving to Beijing, China, that same year to manage funds for an organisation involved in helping migrants and channeling humanitarian aid in the region.

Sylvia with Wang E-hai, a wartime sex slavery survivor in China who was taken to be a comfort woman when she was 14 years old.

During her time in China, she met several North Korean trafficking survivors in China on the railroad. It was life-altering for her to see that the phenomenon of “comfort women” was not just a thing of the past. It was repeating itself in modern day forms.

She would later write about these experiences in her third book, a memoir called A Long Road to Justice.

Partnering a Singaporean missionary in China

In 2011, a Singaporean missionary in Lanzhou reached out to Sylvia after they met through a friend.

The missionary had been helping several “comfort women” survivors in China, especially the ones who were living in dank caves in desperate circumstances and another woman who had cancer and needed medical support.

The Singaporean missionary told Sylvia that she had a dream about a Korean woman dancing in a hanbok (traditional dress) on top of a rainbow that bridged China and Japan.

She felt Sylvia was the right person to work with to produce a documentary on a Japanese Christian reconciliation team that went to China to apologise to comfort women survivors there.

Sylvia dressed in a hanbok (Korean traditional dress).

Sylvia ended up travelling with her to Shanxi to film the documentary entitled Healing River.

The film documents the journey of a Japanese team of Christians as they visited a group of “comfort women” Japanese military sex slavery survivors in the Qinxian and Wuxiang areas in Shanxi province from 2008 to 2012. They used various art forms to offer genuine apologies to the survivors and their families.

Sylvia at opening of the Nanjing Comfort Women Museum in 2015. Her book and film “Healing River” were showcased there.

The film was later screened in churches, schools, and universities in China, Hong Kong, Canada, and the US as part of a campaign to help people let go of generational racial hatred towards the Japanese.

The work of reconciliation is central to her Christian faith. For God has reconciled us to Himself through Jesus’ death on the cross.

“Usually after the film ended, some people would be crying. The film moved them because some were touched that there were Japanese people willing to say sorry, while others said their grandparents or parents were affected by the Japanese invasion of China, and they still carried hatred,” said Sylvia.

At the end of the screening, Sylvia would ask people to raise their hands if they had ever felt generational racial hatred that was passed down from their grandparents or parents. She then asked them if they were willing to release this hatred before leading them in a prayer of forgiveness towards the Japanese.

“It was meaningful for me to be able to bring change as a bridge between people groups and catalyse healing of generational pain and racist attitudes towards the Japanese, especially among young people,” said Sylvia.

For her, the work of reconciliation is central to her Christian faith. For God has reconciled us to Himself through Jesus’ death on the cross, she said, and it is because of this cross that we can reconcile with one another, as it is written in Ephesians 2:14-16.

Sylvia speaking on wartime sex slavery in Atlanta to the Comfort Women Statue Memorial Task Force and other groups.

“It feels impossible in our ‘flesh’ to reconcile with our ‘enemies’ or those who have hurt us profoundly.

“So, we need God because we could pay lip service and just say a ‘sorry’ but if there’s no heart change, there’s no power to the apology and therefore true and lasting reconciliation cannot happen. It is miraculous when any kind of reconciliation happens,” said Sylvia.

Raising awareness on modern forms of slavery

In 2011, God led her to relocate, once again, to Hong Kong.

“It was meaningful for me to be able to bring change as a bridge between people groups and catalyse healing of generational pain.”

She worked as a news anchor and producer with TVB. The following year, she interviewed Matthew Friedman, a United Nations director and US diplomat, for her TVB documentary on modern slavery in China, Thailand and Hong Kong.

“Slavery is not just a historical issue; it exists even today. History is repeating itself. A constant stream of impoverished women and girls have been, and are being, enslaved and abused in the Asia Pacific region, whether through forced marriage, sexual exploitation or forced labour,” said Sylvia.

Both of them became fast friends and emailed several times a day because they were both passionate about the fight against modern slavery. At that time, Matthew was launching the Mekong Club, a non-profit organisation that aimed to mobilise the private sector to take the lead in the fight against modern slavery.

Yet corporations and banks were not responding much to his cold call emails so Sylvia helped get him access to them through the journalism contacts that she had.

Sylvia teaching about wartime Japanese sex slavery at the City University in Hong Kong in March 2018.

“Matthew faced much difficulties in his pioneering work in fighting modern slavery. We were on our knees praying a lot at that time. It felt like a test that we had to persevere through and pass,” said Sylvia.

Their partnership turned out to be very fruitful. It led from those early years when no one knew about human trafficking and outrightly denied its existence to the stage where leading global banks and top brands are now seeking to work with the Mekong Club to help eliminate modern slavery and anti-money laundering from traffickers’ criminal profits.

Sylvia filming a documentary on child and women trafficking in Cambodia.

Sylvia won the prestigious International Human Rights Press Award for her three-part documentary series on human trafficking in China, Hong Kong and Thailand in 2013.

She also led a Hong Kong-based movement of Passionate Compassion against human trafficking that involved more than 120 churches, NGOs and organisations, and later expanded to other countries, including Malaysia, China, Canada, South Africa and the US.

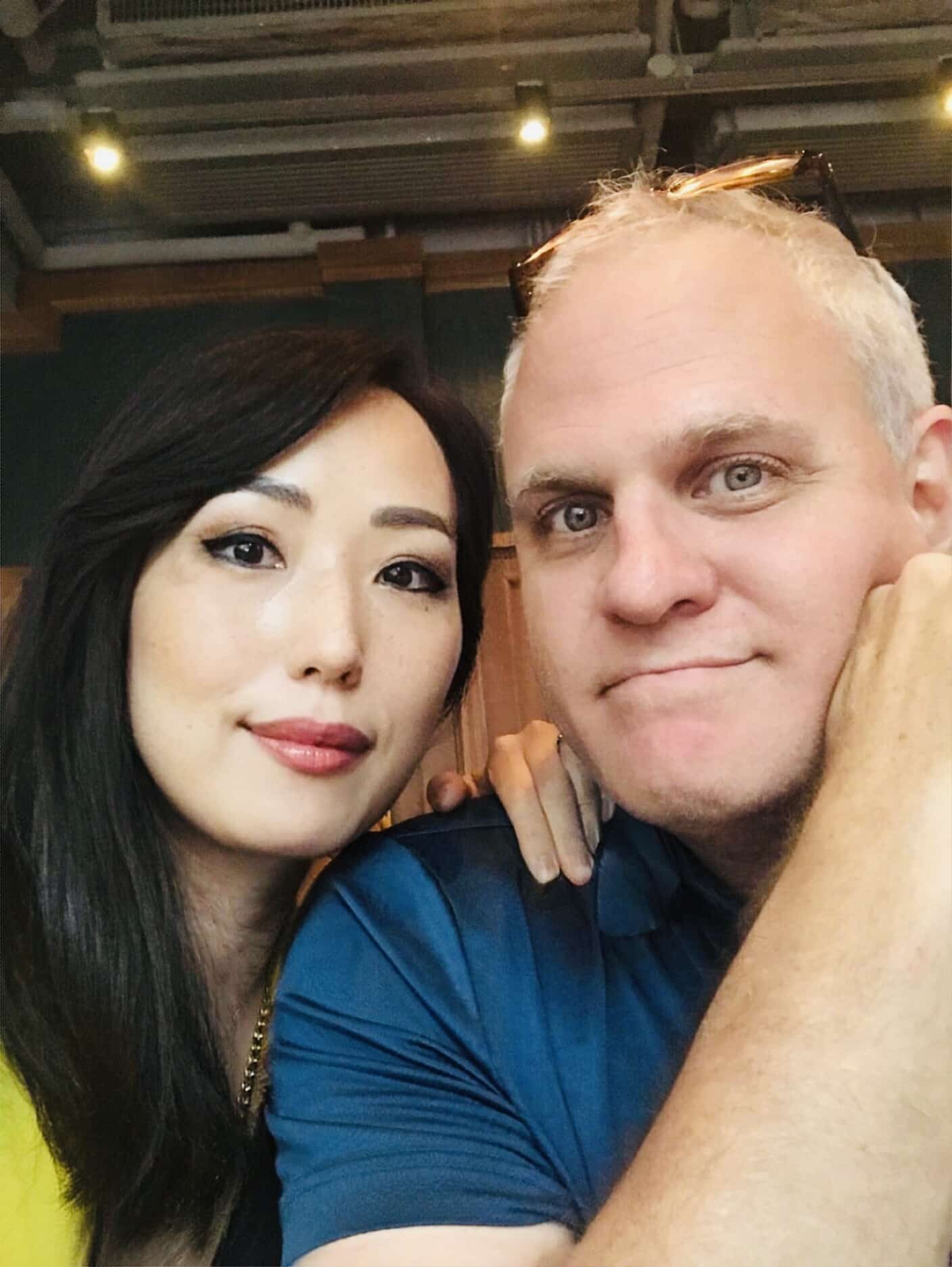

Sylvia Yu and her husband Matt Friedman are partners in love and life causes.

As they pioneered the anti-trafficking movement in the marketplace as well as in Asia and beyond, Sylvia also fell in love with Matthew and married him in 2014.

In the years ahead, she would also write her third book, A Long Road to Justice: Stories from the Frontlines, published by Penguin Random House SEA in Singapore.

Book cover of Sylvia’s third book, a memoir of her stories from the frontlines in Asia.

It is a memoir that traces her journey of fighting for and raising awareness of modern slavery.

In her book, she shows that though wartime sexual slavery happened in the past, it repeats itself in various forms of exploitation today.

Human trafficking victim Jean at a rehabilitation shelter in Manila, Philippines, in 2017.

This includes North Korean refugee women being tricked into sexual slavery or sold as brides into violent marriages to Chinese men, the Hong Kong flesh trade, the child labour trafficking of underaged maids and other forms of human trafficking in Southeast Asia.

“We were on our knees praying a lot at that time. It felt like a test that we had to persevere through and pass.”

A TV series based on her latest book is being developed with the support of an executive producer from Singapore.

It is a mystery to Sylvia as to why God called a gangly immigrant kid to champion social justice and reconciliation work in the media and entertainment sphere.

“Perhaps if I didn’t heed the call, he would have chosen someone else.

“Perhaps – like Esther in the Bible – my background, my ethnicity, my skills, experience and personality were what was needed to carry out His assignments,” said Sylvia.

“I have learned that I can really trust God with my life and future. All of my jobs and open doors have literally fallen in my lap.

“His ways have been far better than what I could have planned for myself.”

RELATED STORIES:

She gave $50 to a single mum to learn to sew. This would multiply into livelihoods for 80 more women

Breaking the silence: A foreign domestic worker and rape survivor’s story of healing

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light