Her father left when she was a few months old … but loving adults journeyed with her, inspiring her to do the same for other families

by Christine Leow // July 28, 2021, 10:08 pm

Now head of community youth movement FamChamps, Delia Ng believes that with guidance and support, youths can rise above their family situations to raise strong families of their own. All photos courtesy of Delia Ng unless otherwise stated.

The first time Delia Ng met her father, she was seven years old. It was a court-ordered meeting.

“When I was a few months old, my father left the family. I never had a chance to see him when I was growing up,” Ng, now 31, told Salt&Light.

“There were no photos of my father,” she said. “I only knew his name which appeared in my birth certificate.”

Ng currently heads FamChamps, a community youth movement that raises young champions to bring change to their families and the community.

Her mother had custody of Ng and her two brothers, who were eight and nine years older.

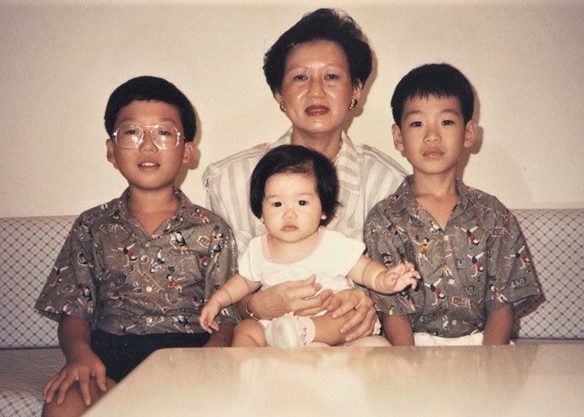

A family photo with her mother and older brothers taken in 1990 when Ng was eight months old.

“When the marriage broke down, the court ordered my father to see my brothers but I was not part of the arrangement though I don’t know why.”

With her father gone and her mother “grieving the loss of the marriage”, home life was fraught with “bitterness, anger and frustration”.

“The court ordered my father to see my brothers but I was not part of the arrangement.”

“There was quite a lot of instability in the home and frequent arguments between my brothers and my mother.”

When Ng was five, her two brothers moved out.

“All I could remember was that they packed up their belongings and left. I didn’t know where they went.”

Ng’s brothers had cared for her when their mother worked multiple jobs to support the family.

“We were very close growing up. They were my playmates and my companions. My brothers were my heroes.

“When they left, there was no way to contact them. I remember longing to hear from my brothers, and to find out where they went, what they were doing.

“It was a double-whammy for me. I already felt very abandoned by my father.

“I felt I had to fend for myself.”

Ng with her oldest brother, Aaron Ng, sharing their life story with youths to encourage them that each can influence their family.

Ng later discovered that her brothers had gone to live with their paternal grandparents before moving in with their father.

“My mother felt very betrayed,” Ng said.

Desire for acceptance

Her parents’ divorce was especially hard on Ng because they are Christians.

“I found it difficult to reconcile the notion of a loving God with what was happening at home. That was something that derailed me.

“As a child, when we sang There is None Like You, the lyrics ‘suffering children are safe in Your arms’ was an irony because my life was unstable.

“I felt I had to fend for myself.”

“I often wondered, ‘If God loves me, why did my life turn out this way?’”

In Primary 6, after attending church every week and seeing that “my home was not a safe place and I just couldn’t understand what love was”, Ng stopped going.

“By then, I could assert my will. I decided that youth service was not for me. I wasn’t interested.

“My mum still insisted but there wasn’t really much she could do.”

Despite the seeming rebellion, Ng longed for her mother’s approval.

“I felt that I just needed to make her proud. I wanted her to think it was a worthwhile decision to keep me and raise me.”

“No matter what accolades I received, I continued to feel empty and unsatisfied.”

Her mother was not one to express love in words or touch. The young Ng found it difficult to understand the quiet sacrifices her mother made was really love in action.

“As a result, how I wanted her to show me love and concern were unmet.

“There was lots of tension and abrasive conversations.”

Ng ended up, in her own words, competitive and ambitious. She hoped that her achievements and accolades would give her the acceptance and affirmation she longed for – if not from her mother then from those around her.

“However, no matter what accolades I received, I continued to feel empty and unsatisfied.”

Ding-donging

During this time, Ng was attending a mission school. So though she no longer went to church, she had Christian friends who would share the Gospel with her and invite her to their churches on special occasions.

There were also “very personal God encounters” that tugged at Ng’s heart.

At age seven, when she was ordered to meet her father every week, she refused. Because by then, he was a stranger to her. So the meetings stopped shortly after they started.

“How was it possible that the person could so accurately speak into my situation? They didn’t even know me.”

Around that time, she went to a children’s camp at a church that was not her own. There, she responded to a call to be prayed for.

“The person praying for me said, ‘Even though your earthly father will fail you, your heavenly Father will not fail you.’

“I didn’t know how it was possible that the person could so accurately speak into my situation. They didn’t even know me. How could they know this?

“I realised that God is so real.”

Yet, in the midst of these revelational moments was the reality of the situation at home. Ng was conflicted.

“I was ding-donging. I knew that God is real but my parents still did this. How does that make sense?”

Removing the rock from her heart

At 15, Ng was in church when there was a call to release long-held anger that had been a burden for so long.

“I prayed, ‘I’m so tired of being angry. I just don’t want to be angry anymore. I want to be set free from this bitterness.’

“And I saw a hand reaching into my heart and taking a rock from my heart. I felt joy and freedom I had not experienced before.”

“I’m so tired of being angry … I want to be set free from this bitterness.”

Ng would later come across Ezekiel 36:26 and realise that God was “replacing my heart of stone with a heart of flesh”.

“It made me realise who God is and how personal this heavenly Father is to me.

“I realised that while I rejected the idea of knowing my father, actually, at the heart of it, I did yearn to know who he is. I felt that it was essential – to who I was as a person, to the forming my identity – that I got to know my father.”

Ng quietly initiated a meeting with her father. She was encouraged by her second brother who had, by then, started working, and was “very intentional in reaching out to me”.

But it would be many years before she could fully embrace God.

Unconditional love

“I continued to keep an arm’s length from God. While I professed to be a Christian, I maintained a mindset of self-sufficiency and didn’t see a need to be discipled in a local church.”

It was only in university while on an overseas internship with a Christian organisation that God’s Word spoke to Ng.

Ng (left) in 2010 conducting a youth workshop while at an internship abroad.

She was reading Philippians 3:7-12.

“I was particularly struck by verse 10. I read it aloud and, after reading it repeatedly, the words ‘I want to know Christ – yes, to know the power of His resurrection and participation in His sufferings, becoming like Him in His death’ cut through my heart and spirit.

“It dawned on me that even though I grew up in a Christian environment, God knows me, but I had never known Him. The power of Jesus’ resurrection is a power that can bring life to something that was once dead. Little had I realised that God had never stopped pursuing me.”

“Proverbs 3:12 revealed the Father’s heart to me. He is a gentle and loving Father.”

Ng was determined to “let go of what I used to hold tightly to and fully align to God”.

She returned to Singapore and found herself a church.

“One of the truths that grounded me through this journey was Proverbs 3:12, ‘For the Lord corrects those that He loves, just as a father corrects a child in whom he delights.’

“Growing up, I associated discipline and correction with harshness, accusation and anger. This verse revealed the Father’s heart to me. He is a gentle and loving Father.

“Through God’s relentless pursuit in demonstrating unconditional love and undeserved grace, God restored my identity.

“I am not abandoned and my life is not a mistake. God redeemed my past for His purpose.”

A part of happy families

God would redeem Ng in other ways.

Though her family life was chaotic, she had plenty of opportunities to be a part of happy families.

“The church family played a huge part in raising me with my mum.”

“My godparents were integral in helping me have hope for a happy marriage.”

When Ng’s mother had to work late or go for night classes, family friends from church would welcome Ng into their homes after school. They gave her dinner and a loving environment of care.

Ng’s godparents from church would take her out every Sunday for meals so her mother could attend Bible study classes or be part of a women’s group. They were “helpful role models”. Now in their 70s, they continue to be a big part of Ng’s life.

As a child, she used to be “very envious and bitter” when seeing families “not just functioning, but also enjoying each other”.

“Why is it that people could be like that but I couldn’t?,” she asked herself.

“But, looking back, it was helpful.

“My godparents were integral in helping me have hope for a happy marriage,” she said.

Teachers of hope

Teachers in school also rallied around Ng.

“I didn’t trust adult figures or authorities. But my teachers believed in me and were willing to see past my mistakes.”

Ng recounted an occasion when she was just eight and had been caught for shoplifting. Her mother informed the school, asking for help to manage Ng.

The school sent Ng for detention – she was given a desk in the principal’s office after school.

Despite being mischievous and having been placed in detention in primary school, Ng (centre at microphone) had a nurturing school environment with caring teachers who were intentional about developing her strengths.

“She coached me in my school work and talked to me. She befriended me. It was a very pastoral kind of environment.”

Ng became a prefect in secondary school, but admitted she “didn’t really take pride in my responsibility”.

But her prefect mistress mentored her and shared with her a different perspective of life.

The school sent Ng for detention – she was given a desk in the principal’s office after school.

In the church where Ng would later settle, mentors would journey with and help her “heal from hurts and unravel ungodly mindsets”.

“They helped me reconcile my faith with my life. I learnt to see that as humans, there may be fallen nature and brokenness in each of us.

“God intended for things to be good but because of the action or inaction of these people, we may have to face consequences.

“So, even though I had expected my parents to be a source of stability and comfort, I learnt not to be angry when those things were left unmet in my life.”

Now a mother of two, Ng understands even more deeply that there is “no perfection in parenting”.

Ng with husband Josias whom she married in 2014. Their son, is turning 2, and daughter is 3.5 years old.

“We just have to trust in grace that would see us through and His sovereignty in our lives. God’s hand is never too short to reach out.

“I have seen how He continued to rescue me in my life.”

A vessel of empathy

Among the loving adults who gave Ng stability was a maternal aunt who would plant in her the seed of desire to help others.

When Ng’s home life fell apart, this aunt – who studied social work and worked in a child welfare department – came alongside Ng’s mother to offer support.

“She was a trusted adult figure in my life growing up. She exposed me to how community support is needed to build a whole society.”

Inspired by her aunt, Ng went into social work and became a child protection officer – a job she held for three years.

A maternal aunt would plant in her the seed of desire to help others.

“It was a defining period of my life. It deepened my walk with God and helped me discover what I am called to do in terms of serving the community and God.

“I discovered how God could use me as a vessel to empathise and to support families.”

She also saw the need to take a preemptive approach to preventing family relationships from breaking down.

“I saw a normalisation of maladaptive behaviour.

“On multiple occasions, parents would tell me, ‘I grew up in such circumstances, I encountered this myself as a teen. Now that it is happening to my child, I believe my child will somehow find a way to survive and grow out of it.’”

Ng (bottom, left) with the FamChamps team.

Ng also saw children who longed for home – no matter how unstable home was.

“They told me, ‘Even though you want to put me in a place of safety – in a home or foster family – I still yearn to be with my biological family. Even though I know I risk being hurt or disappointed or that it is not helpful for me emotionally, there is no place like home.’

These are children under 16.

Seven years ago, Ng joined FamChamps in an effort to support youths and champion the family unit.

“I discovered how helpful it is for a young person to be guided in their life – especially when they find it difficult to relate to their families.”

Fortifying families

FamChamps aims to help families on several levels. It starts by being a bridge to connect children to their parents.

They also hope to give youths “a fuller picture of how healthy and strong marriages are essential to laying the foundation for family life”.

Connect with Family, for instance, was a campaign that featured a series of videos (one below) of youths attempting to strengthen their family relationships. The campaign reached more than 40,000 people.

FamChamps offers courses as well to raise conversations about topics related to families.

This year, it organised Be.Live, a conference that got youths talking about what family means to them. It was attended by nearly 700 from over 20 educational institutions,

Following on from this will be a three-day virtual camp in October, which will include group discussions and interactive learning.

Ng (third from left), during a leadership and team-building camp, with some members of the first FamChamps Council.

“We want to get the participants to set measurable goals to kickstart something in their own homes.”

For instance, youths could commit to help out with chores or do their part to alleviate the load on their parents.

“Youths need to see that they belong to the family and can contribute to the atmosphere of their home.

“There is no one-size-fits-all to family life. It depends on where they are with their families. Some families don’t sit down together for family meals. Some do, but they don’t talk.

“Depending on where they, the facilitator will help them identify the next feasible step.

The next generation of champions

FamChamps is also raising a generation of young people to champion the family. Its first council, elected in 2019, includes seven participants who attended a FamChamps camp when they were in secondary school. They are now in their late teens and early 20s.

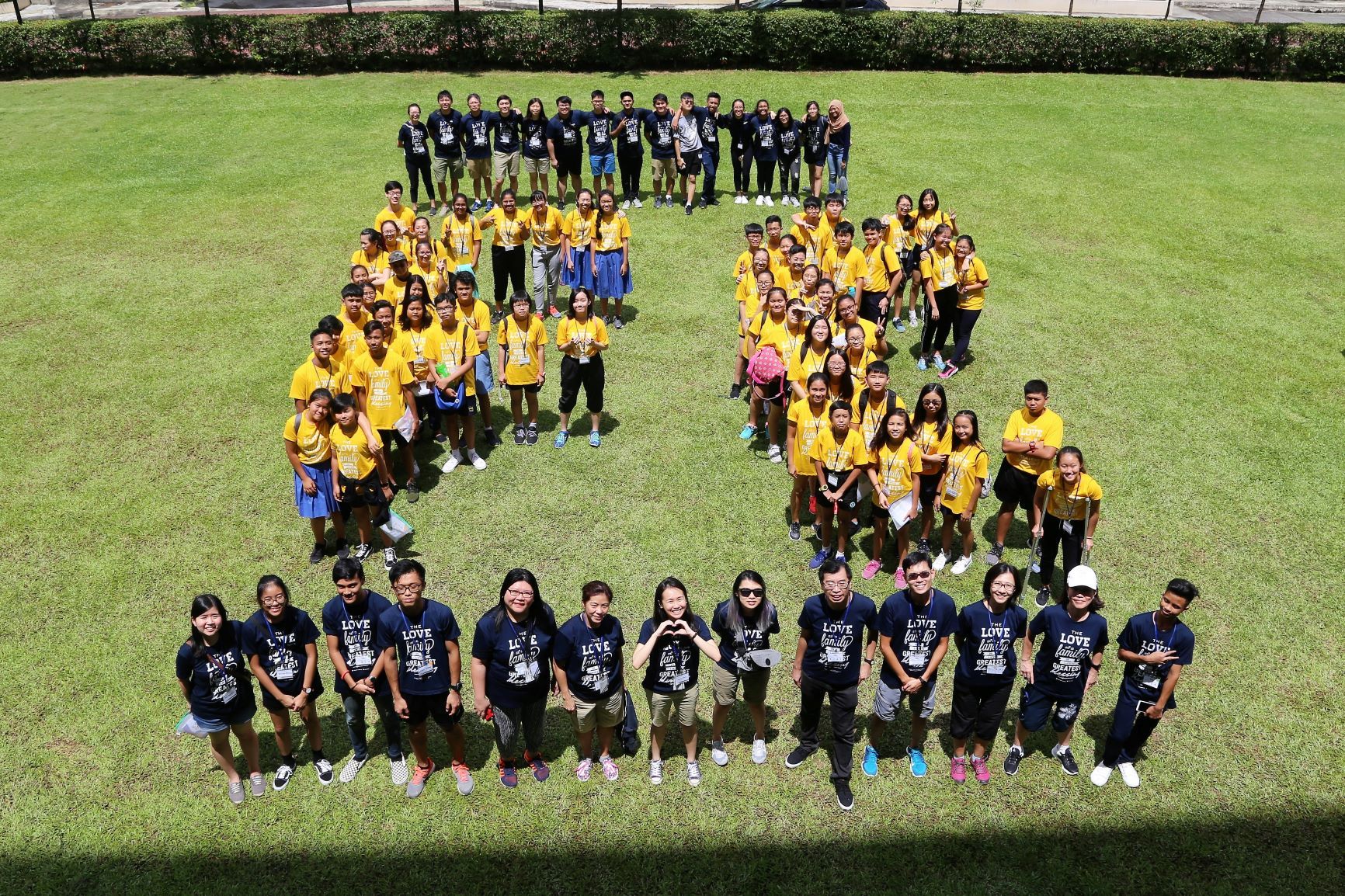

Youth participants and their mentors at a FamChamps camp in 2018. Photo courtesy of FamChamps.

After the camp, they continued to return for training and development with the FamChamps community.

As part of the FamChamps Council, they receive regular mentoring and group coaching. They also organise ground-up projects in their journey as Family Champions.

Senior members of FamChamps singing its theme song to rally their juniors at an awards ceremony in 2019. Photo courtesy of FamChamps.

Then, there is the personal support FamChamps is able to offer because of the “foundation of friendship” and the relationships that they’ve built.

Ng shares that one of the youths turned to them last year when her parents filed for divorce. She was 20, and in a state of shock.

A happy ending

“We cannot change the family of origin,” said Ng. “But if we have a strong foundation of beliefs and values for family life, we can fortify families for the future.”

Ng can certainly attest to this. After a rocky start, she now considers her mother her confidante.

Ng celebrating Mother’s Day with her mother this year. Now that Ng is a mother, she has come to understand and appreciate her mother’s love for her.

“We didn’t get here overnight. When I chose to meet my father when I was 15, I did it behind my mother’s back. When she found out, she felt very betrayed.

“We began to have deeper conversations.

“By choosing to reconcile with my father, it does not negate what my mum had done to raise me.”

“I shared with her that by choosing to reconcile with my father, it does not negate what she had done to raise me. I really desired a personal relationship with my father and my mother. Both of them are unique and irreplaceable to me.

“She softened a bit after that.”

Ng also sought her mother’s forgiveness for times when she hurt her and rebelled.

Ng reconciled with her father, too. They see each other about once a month.

“It’s interesting. I discovered that we have many things in common even though I didn’t grow up with him. We share common interests in nature and baking.”

RELATED STORIES:

He tried to run away, but God taught this ultra-marathoner to run from depression instead

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light