Today, most modern managers are committed to the ESG – environmental, social, governance – approach. The result is changes in compliance and sanctions, but not changes of heart that would be needed for a genuine transformation of capitalism, writes the author. Photo by Executium on Unsplash.

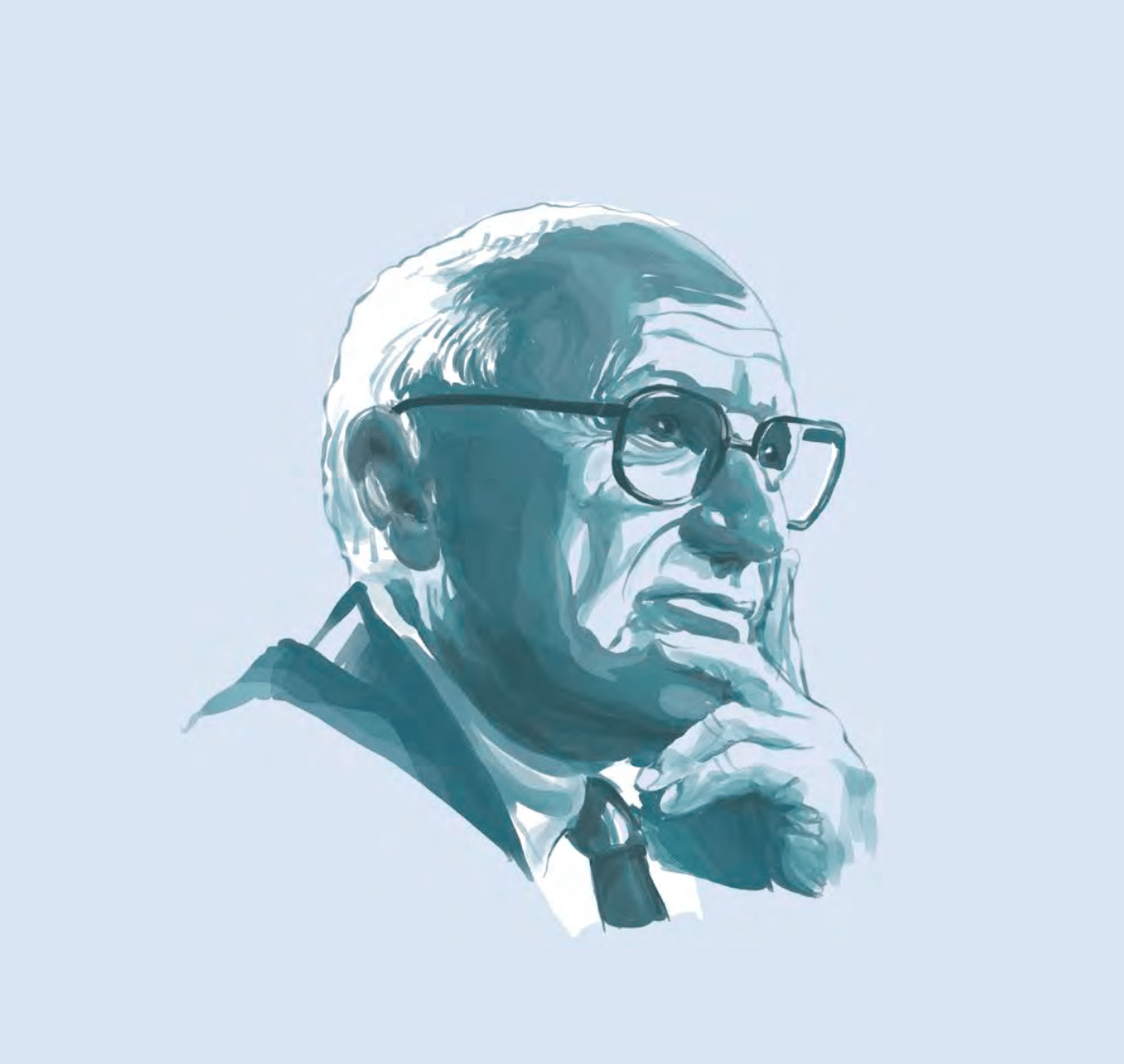

Modern managers have only a weary smile left for the theory of Milton Friedman (1912–2006), the American economist awarded with the Nobel Prize for Economics:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud.”

When done from “above the sun”, work or business finds meaning and purpose.

Two recent global scenarios reveal much of today’s corporate culture. In January 2021, WhatsApp announced changes to its privacy policy and terms of service. The news stoked users’ fears over broader data sharing with WhatsApp owner, Facebook, raising privacy concerns, and sparked a mass exodus of subscribers to other messaging apps like Telegram and Signal.

It was precisely such privacy concerns that led WhatsApp co-founder Brian Acton to part ways with Facebook chiefs Mark Zuckerberg and Sheryl Sandberg in 2017. He left before his final tranche of stock grants worth US$850 million vested. Acton’s decision was described by Forbes magazine as “perhaps the most expensive moral stand in history”.

Big Tech’s scrutiny

Acton who is a pro-privacy zealot and boasted “no ads, no games, no gimmick” under his watch, had then balked at the Facebook chiefs’ plans to monetise WhatsApp through targeted ads, and the sale of business analytics tools that risked encroaching on WhatsApp’s end-to-end encryption. He had proposed to the Facebook chiefs to monetise the messaging service by charging heavy users a small fee. But his proposal was shot down, he believed, on grounds that it was far less lucrative.

They know more about everything than anyone ever has in the history of mankind.

Driven by the pursuit of profit, Big Tech has revolutionised the way we live. Unknown to us, our lives are constantly under their scrutiny 24 hours a day, seven days a week. They know everything we have purchased, everywhere we have been, and everything we want. In short, they know more about everything than anyone ever has in the history of mankind, leveraging on the power of data and artificial intelligence.

The Big Techs not only generate a lot of profit, but they virtually captured the brightest and most innovative minds in the world under their employment. And what are they doing with all of this? Well, the blunt truth is that their main focus is selling tiny little ads that appear on every screen you look at. These businesses, after all, were started to make money, and, ahem, are they lapping it up!

The inequality virus

Moving to a vastly different scenario, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned the Covid-19 vaccine divide between rich and poor nations is worsening by the day.

“Rich countries are rolling out vaccines, while the world’s least developed countries watch and wait,” said WHO Director-General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

Not only that, the pandemic has spawned widening inequalities. Today’s profit-driven world has enabled a super-rich elite to amass wealth in the middle of the worst recession since the Great Depression, while billions of people are struggling to pay bills and put food on the table.

The two scenarios are just outcomes of shareholder capitalism which has embedded much of Wall Street’s culture and egged corporations on the path of profit maximisation.

In search of perfect markets

Celebrated economist and Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman’s seminal essay, headlined “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits”, published in The New York Times of September 13, 1970, became the cause célèbre for free market and shareholder capitalism. It was arguably the most consequential economic idea of the latter half of the twentieth century.

Friedman warned of the danger of thinking about anything but profit. Everything else is thought to lead to inefficiency and self-indulgence. In short, Friedman believed that the only business of business is business.

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud,” Milton Friedman wrote. Illustration courtesy of Go magazine.

Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” conjecture which said that the pursuit of self-interest would lead, as if by an invisible hand, to the well-being of society found resonance with him. Hence, profit maximisation, he believed, would lead to a maximisation of social welfare.

Friedman has his detractors. Such a belief, Prof Marianne Bertrand of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, in a New York Times interview, explained, rested on the assumption of markets functioning perfectly. “Unfortunately, such perfect markets exist only in economics textbooks.”

Big Techs are not rule-takers but rule-makers

Functioning markets operate under a set of rules or norms, whether explicit or implied. Do today’s Big Techs and corporate behemoths truly stay within the rules of the game?

While there is a trend towards corporate virtue, the pursuit of profit remains the dominant force.

The sad truth is that they are not rule-takers or price-takers, but rule-makers. They have also become arbiters of truth.

“They play games whose rules they have a big role in creating, via politics,” wrote Martin Wolf in a Financial Times opinion piece.

While there is a trend towards corporate virtue and stakeholder capitalism (as opposed to shareholder capitalism), the penchant for pursuit of profit remains the dominant force behind enterprise. Major corporations using the cloak of supporting progressive causes are in effect doing so to protect their bottom line. The rising tide of woke culture seeping into boardrooms is giving this another spin.

The rise of woke capitalism

Increasingly, corporations are sucked into woke capitalism, a term coined by The New York Times columnist Ross Douthat. They are paying homage to the cultural “left” to avoid criticisms and win acceptance in order to fulfil their primary objective: Making money. So-called progressive values have become powerful branding tools. Corporations today are under siege to embrace political correctness to avoid being “cancelled”. Capitalist enterprises and the cultural “left” have become strange bedfellows for the sake of mammon.

Companies that operate in a sustainable manner would “provide better risk-adjusted returns to investors”.

Notwithstanding this, there is still a welcome shift towards socially responsible investment, spurred by concerns on climate change and the environment as well as social justice issues. ESG (environmental, social and governance) themed investing is becoming mainstream. Currently, over US$100 trillion in investments are managed by firms that have signed on to the United Nation’s Principles for Responsible Investment.

Larry Fink, CEO of multi-trillion-dollar asset manager BlackRock, predicted a “fundamental reshaping of finance” that would see investors allocating more capital to businesses that are addressing climate change and its socioeconomic implications. Companies that operate in a sustainable manner, Fink argued, would “provide better risk-adjusted returns to investors”.

Is ESG more than a public relations strategy?

Prof Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum (WEF), wrote in his book, “We can’t continue with an economic system driven by selfish values, such as short-term profit maximisation, the avoidance of tax and regulation, or the externalising of environmental harm. Instead, we need a society, economy, and international community that is designed to care for all people and the entire planet.”

Without inner change, ESG is simply behaviour modification, aided by the law.

The ESG trend has helped focus attention beyond financial capital to natural, human and social capital. But with public opinion weighing heavily in the direction of ESG, there is cynicism that much of the pious corporate proclamations are little more than opportunistic public relations strategies.

ESG is only the latest iteration of its precursor concepts such as corporate social responsibility and the triple bottom line. While fresh ideas have emerged, a key difference is its focus on climate change and the environment. The moral necessity of ESG has gained wide acceptance. But it is heading not in the direction of cultivating true altruism but in enforcing behavioural change through compliance metrics and external sanctions. Regulations have limited effectiveness as they are quickly circumvented when there is no real change. Without inner change, it is simply behaviour modification, aided by the law.

Exploring spiritual capital

Only spiritual change from inside out can bring the desired human wellness and flourishing. It is not just a mindset change but a heart-set change that is needed for genuine transformation to take place in the world. That takes us to the oft-forgotten but most needed recognition of the importance of spiritual capital in human enterprise.

Rooted in faith, spiritual capital infuses a strong sense of purpose and mission, and promotes the practice of not only virtue but faith in business for human betterment. Faith has a powerful impact on lives, and similarly so, on business. It shifts the focus of enterprise beyond the material and the self, offers hope and builds trust, a key ingredient for business success. It is transformational.

Faith offers hope and builds trust, a key ingredient for business success.

Speaking of spiritual capital, Michael Novak of the American Enterprise Institute said: “Capitalism carries in its wake the potential for immense transformation, a true and permanent change that is moral in nature. Those nations, peoples and businesses that neglect the moral ecology of their own cultures cannot enjoy the fruits of such transformation and capitalism must be essentially moral or it falters, declines, and fails. Spiritual enterprise is capitalism in its most profound … form.”

Every religious faith has its own prescription for spiritual capital. However, the Christian faith offers a unique proposition that gives business a redemptive purpose beyond just the temporal. Hence, the Biblical model of business can best be described as a redemptive enterprise.

King Solomon writing in the book of Ecclesiastes in the Bible reminds us that work “done under the sun”, that is, from a human perspective without God, is “vanity and grasping of the wind”. It is a meaningless activity. However, when done from “above the sun”, that is from God’s perspective, work or business finds meaning and purpose. This is Part 1 of the article. Carry on reading Part 2 here.

This article first appeared in Go, a Christian magazine in Europe, and is republished with permission. It is an extract of a book the author is writing.

RELATED STORIES:

Financial capitalism is outdated, says economist who offers alternative for purpose-centric business

“The ordinary man, you and I, can make a difference”: Retired Judge Richard Magnus

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light