Addicted to drugs, he broke his father’s heart. Years later, his sons would do the same

TRIGGER WARNING: This story contains mention of suicide. Reader discretion is advised.

by Christine Leow // April 5, 2024, 5:18 pm

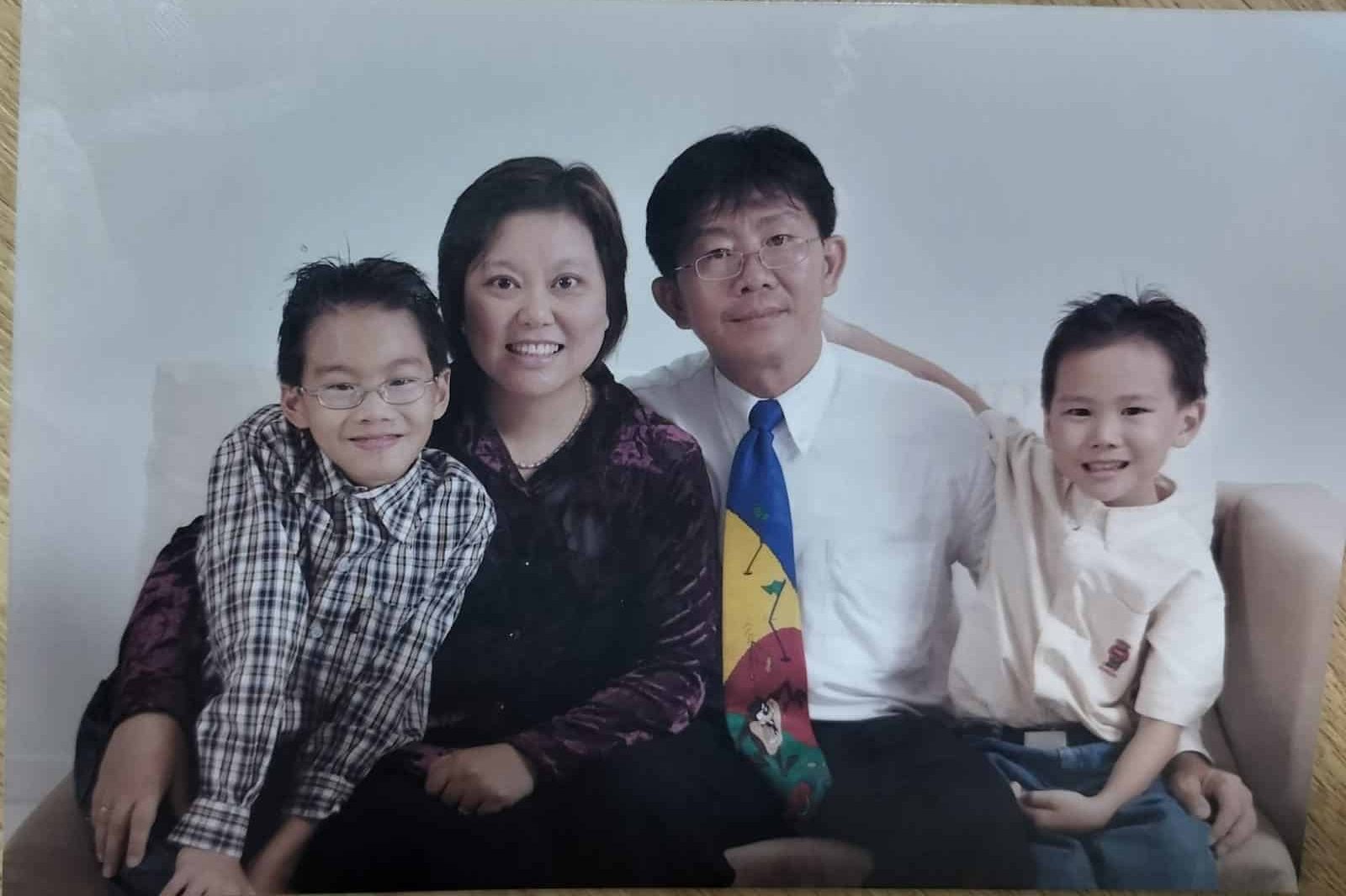

Retired pastor Jabez Tan was a drug addict in his 20s. He and his wife, Chiew Peng, a pastor and now a counsellor, struggled when both their sons became addicted to drugs. All photos courtesy of Jabez Tan.

It was 1975 and 18-year-old Jabez Tan was due to enlist for National Service (NS). Instead, his family put in a request for a year’s deferment because his father had passed away. The elder Tan had killed himself.

“I was on drugs and he knew it,” Jabez, 67, told Salt&Light.

At the time, he was friends with a group of motorcycle racers and had been exposed to drugs a year before. To feed his drug habit, Jabez would extort money from the shops in his neighbourhood.

At his father’s wake, Jabez knelt before the coffin and vowed he would not go back to drugs.

He had gone to a bird shop and demanded $50. The owner of the shop knew Jabez’s father and told on him.

“My father confronted me. I denied I was on drugs and argued with him. He was very sad.”

Three days after their quarrel, his father jumped from the block of flats in which they lived.

His father had been a troubled man long before their falling out. He was a gambler and owed money to loan sharks. Because of his predicament, he was also “a bit depressed”.

Jabez’s immediate family – his mother and seven siblings – knew of the situation and did not blame Jabez for his father’s suicide. But he still felt very bad.

“It was the last straw. I felt guilty because I was partly to blame.”

At his father’s wake, Jabez knelt before the coffin and vowed he would not go back to drugs. But it was a promise he could not keep on his own.

A loving home

Unlike many who joined gangs, Jabez did not come from a troubled home. His family was not well-to-do. His father was a port foreman and his mother did laundry for others to supplement the family income.

But the children were well loved. There were four boys and four girls in the family, and his father treated all of them well.

“His language of love was providing for us, buying us things, buying us food.”

“He was not a typical Chinese father. He loved the daughters more. Once when I was jealous of my sisters, he told me, ‘Eventually, your sisters will marry out. So they must have a good life in this family.’

“There were no problems at home. My father was a very loving man. He made sure that even if he lost money gambling, he would still bring money back for mum to feed us.”

As the eldest boy, with two sisters ahead of him, Jabez and his father shared a special bond.

“Dad loved me a lot. If he won in gambling, he would take me out for supper. We used to go to Duxton Plain to eat hokkien mee.

“His language of love was providing for us, buying us things, buying us food.”

Looking to belong

What his parents did not provide, though, was supervision. Jabez was left on his own in a neighbourhood where plenty of gangs were active. When he was 14 or 15, he was invited to join one by a friend. He readily accepted.

“If you don’t ‘wear the shirt’ of one gang, you will ‘wear the shirt’ of another. There will always be people out to recruit you,” said Jabez.

“We were in the gang for identity. I wanted to act tough, to look cool. We smoked, we extorted money.

“My parents knew. They must have known. But they couldn’t stop me. I was very rebellious.”

“It was the thrill of the high, the fun, that kept me going.”

Already a poor student who “always pontang school” (played truant), he dropped out at Secondary Two.

For two years, Jabez was part of the gang. Then in 1972, laws on gangsterism tightened. Many of his gang friends were arrested.

Jabez left his gang to join a group of motorcycle riders. Again, he was prompted by the desire to appear cool. He was 15.

“I joined them as a pillion rider. I enjoyed the thrill of racing.”

It was because of this group that Jabez was eventually exposed to drugs. At first it was just pills.

“I knew it was bad. I would get into trouble, people would beat me up because when you are high on drugs, you do stupid things to offend people.

“But it was the thrill of the high, the fun, that kept me going. I wasn’t worried about anything. I just wanted more of the high.”

Soon, he moved to heroin because “it won’t make you so aggressive”. He became heavily addicted to it.

Army daze

A year after he pledged to quit drugs at his father’s wake, Jabez still could not free himself from the grip of addiction. While serving NS, he was caught for drug consumption and handed over to the Military Police.

Locked up in the army guard room awaiting court martial, he escaped with two others who were with him.

“I got into fights. I acted tough because I had survived the tough detention.”

“Two of us managed to saw off the grill.”

For that stunt, he was sentenced to three months in special detention on top of his 22-month sentence.

“It was a disciplinary barracks. I had to carry heavy sandbags, dig hills, pour the sand into another place. It was heavy work.

“I made a vow to change or else I would indeed be a dog, not a human being.”

But nothing came of this vow as well. When he finished his time in special detention and went on to serve out his 22-month sentence, he got into trouble again.

“I got into fights. I acted tough because I had survived the tough detention.”

Unable to shake off his drug addiction, he would re-offend in 1979 and be sentenced to three years in civilian prison.

“The army discharged me. They didn’t want me anymore.”

The testimonies that persuade

That season of Jabez’s life should have been the most hopeless. Instead, incarceration became his saving grace.

In prison, he met one of his seniors in the army.

“I knew him from detention. He was a very vulgar person. His language … wah! But when I met him again, I saw that his speech had changed. I saw that his life had changed.

“He told me, ‘Go and believe in God. Don’t bother about what people think of you. If you are sincere, go to chapel with me.’

“He always shared his testimony with me.”

“He was a very vulgar person. His language … wah! But when I met him again, his life had changed.”

Then Jabez heard that one of his younger brothers had been sentenced to a reformative training centre for delinquency and drug addiction. He begged his superintendent to let him visit his brother.

“My superintendent scolded me. He said, ‘You yourself are here. What are you going to tell your brother when you visit him?’”

Yet two weeks after the request, Jabez was allowed to see his brother.

“When I talked to him in that hour, I realised he had changed. He had become a Christian.

“He told me, ‘Don’t worry about what others will say, go for chapel service, believe in the Lord.’

“In that hour, he never used one nasty word. In the past, out of 10 words at least one would be vulgar.”

Jabez returned to prison and started attending chapel services.

Finally breaking free

At one chapel service about a year into his sentence, Jabez responded to an altar call and gave his life to Jesus.

“The problem with drug addiction is not the physical. It was the social networking.”

The change that followed was almost immediate. Never one to sit still during lessons or have an interest in books, Jabez suddenly developed a desire to study.

“I wanted to understand the Bible. I requested a dictionary from my superintendent so I could improve my English.”

He even passed an English test that would allow him to prepare for his ‘O’ level examinations. When he was released, Jabez was placed at The Hiding Place (THP). The co-founder of the halfway house, Ps Philip Chan, was himself at the prison gate to receive him.

At THP, Jabez finally found a place in which he truly belonged.

“The network of people helped. There were a lot of volunteers who were loving people. I made friends with them. Positive peer pressure.

Jabez enjoyed the sense of belonging he felt when he was part of a gang. That was what made breaking away from drugs so much more difficult for him.

“The problem with drug addiction is not the physical. You can deal with that easily. It was the social networking.

“At THP, I managed to develop good friendships and the accountability that helped me break away.

“And there was the Word of God. Everyday, we were expected to do our Quiet Time.”

The spectre of addiction

Jabez would develop a desire to serve God full-time. He spent two years in India under the auspices of Operation Mobilisation (OM) before becoming a helper at THP.

After that, he went to Singapore Bible College (SBC) and earned, first a diploma, and then a degree in Theology. It was at SBC that he met his wife Chua Chiew Peng.

Jabez and his wife Chiew Peng (left) used to quarrel about the way each dealt with their sons’ addiction. He felt she was too harsh and she felt he was too soft with them. But, in prayer, they united to intercede for their sons.

He went on to pastor a church in Singapore, graduate from Regent College with a Master of Arts in Christian Studies and then return to Canada to pastor another church.

It was during his second stint in Canada that both his sons, then in their teens, became addicted to drugs. For someone who had personally battled his own demons with drugs, this hit too close to home.

“As a pastor, I struggled. I felt like a failure.”

“I felt sad. But I understood.”

Because of the liberal culture in Canada – “in high school, they would start drinking and smoking marijuana” – Jabez hoped that it would be all “part of growing up” for his sons.

Chiew Peng did not share his views.

“My wife was very strict. She would confiscate their drugs, flush them into the toilet. I was more concerned that they would get into trouble, or that they would be asked to pay for the drugs.”

When it become clear that his sons were more than casual drug users, it pained Jabez greatly. More than anyone, he knew the challenges ahead of them.

“As a pastor, I also struggled. I felt like a failure. My wife, who was also a pastor, struggled even more. All the more we prayed.”

Letting go

When every attempt to get the boys into drug rehabilitation failed, Chiew Peng began to wonder if moving to Canada had been a mistake.

Jabez came to his own conclusion.

“I did question God. But I came to a point when I realised that it was their choice. Maybe they would have a breakthrough after coming to a dead end and come to the Lord.

“I prayed for them. I talked to them. But ultimately it was their choice.”

That resolve to surrender his sons to God was put to the test when the family decided to return to Singapore but their younger son refused to go along with them.

“My younger son said, ‘Dad, you go back. I will never go back.’”

“God is gracious and faithful. He is the God of second chances.”

Jabez, however, was assured that God was in control because of the word he had received.

“I was spending time with God when He gave me verses that He would be with us in the water and in the fire (Isaiah 43:2), and that He would call our children back from the East and the West (Isaiah 43:5-7).

“That was how I decided eventually to come back to Singapore.”

Chiew Peng had received the same verses, confirming that the return was of God. In 2014, Jabez and his older son joined Chiew Peng in Singapore. She had gone ahead of them a few months earlier.

In Singapore, husband and wife went for walks daily to intercede for their sons, especially their younger one who was still in Canada.

“We prayed and symbolically lifted our hands up to commit him to the altar.”

As God promised, the family was reunited. Their sons went to halfway houses in Singapore and, after several ups and downs, finally kicked their drug habit.

Of his and his sons’ journeys through the deepest valleys of addiction and back, Jabez said: “God is gracious and faithful. He is the God of second chances.”

RELATED STORIES:

Love them, just love them: The missionary couple who prayed their prodigal children home

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light