“Many can handle failure. Not many can handle success”: Behind the scenes of André and His Olive Tree with director Josiah Ng

by Juleen Shaw // February 3, 2021, 2:54 am

"Chef André has come to a place where he has recognised that love trumps all. And he's using his talents to love other people, to build up the younger generation," reveals film director Josiah Ng (extreme left). All photos courtesy of Josiah Ng.

It’s not the food you first see. It’s the faces.

The face of Pam, Chef André Chiang’s wife, singing “happy birthday” with melancholic eyes.

The face of pastry chef Mohamed Al-Matin, his mouth a perfect “O” in reaction to André’s shock announcement.

The face of André’s Taiwanese mother as she gives her son a shy side-eye, this famous son of hers who has been away for over 10 years but is sitting beside her now, his words plain but his tone tender.

For a film about a two-Michelin-star restaurant and celebrated chef, there are surprisingly few vignettes of food. And this is exactly how film director, Josiah Ng, 33, wanted it.

“This was a man who had achieved the kind of recognition that a lot of people could only dream about. I was very curious about why he would give it all up,” says Josiah (in pink shirt).

“I was very clear to my producers, my cameramen, my editor that, look, don’t show me too many shots of nice food – I know it’s very nice – but it’s not about the food, it’s about the man,” says Ng of his sleeper hit, André and His Olive Tree.

“If you google Chef André, he has a lot of media coverage and everyone talks about his food, his creative process. Rightly so. But no-one really knew who André was. I really wanted to do a character study.”

The full-length feature film, running in Singapore theatres now, and on Netflix worldwide (sans Singapore), shows the days leading up to the 2018 closing of the multi-award-winning Restaurant André at the height of its success – a decision by Chef André that had stunned the gastrosphere.

“If you google Chef André, everyone talks about his food, his creative process. But no-one really knew who André was.”

Ng, head of film and social content at DDB Group Singapore, first heard the news of the chef’s decision while he was at a film festival overseas. He had been stirred. As someone who had had his share of accolades in filmmaking, the notion of a professional at the top of his game walking away from the awards and recognition piqued Ng’s interest.

What is success if not awards? What is achievement if not public affirmation?

The talented film director opened up to Salt&Light about why he took on the film as a three-year passion project, what it was like working with a self-described OCD chef, and how the film unexpectedly fulfilled a vision God had called him to from the time he was old enough to draw on his bedroom walls.

How did Chef André come to be the subject of your first commercial feature film?

When I first read the news article that Chef André was closing the restaurant, I was intrigued because this was a man who had achieved the kind of recognition that a lot of people could only dream about.

I was very curious about why he would give it all up. Jeff Cheong (now Deputy CEO at DDB Group Singapore), who’s my boss, was with me at the time, and he was the one who seeded the idea of the film.

“In my exploration of Chef André, I found out that there is a lot more (to life) than awards,” says Josiah (left).

On the way to my flight home, I drummed up a quick email to Chef’s PA and, to my surprise, she replied: Sure, Chef is happy to meet you.

The first meeting was nerve-wracking. I had only heard of him through the media. Friends said he was relatively friendly but was known for his OCD-ness.

I went prepared with a deck to tell him who I was, why I wanted to tell his story, what’s in it for him, what’s in it for me, business-wise.

But, surprisingly, when we met, he simply said: “What’s on your mind?” That allowed me to let my guard down, and it became a sharing of hearts. I told him a little about where I came from, he told me about where he came from. And that led to: “You know what, let’s make a movie.” It was as simple as that.

Why did you connect with Chef’s story so strongly?

When I went to film school in Ngee Ann Poly, I got quite good results. In fact, I was the “golden graduate” of the year. It was a huge surprise and encouragement because I never really did well in secondary school.

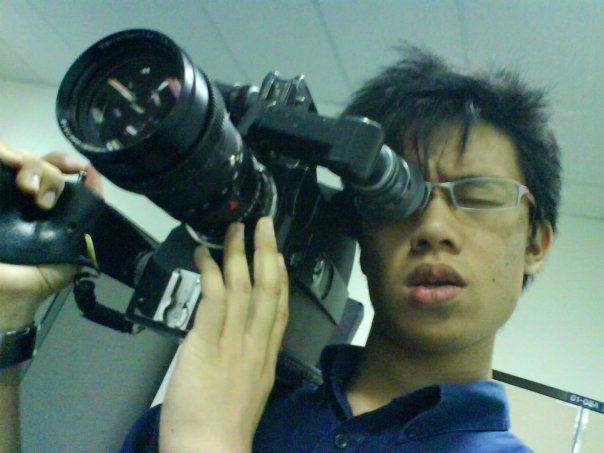

Josiah in film school at Ngee Ann Poly in 2006.

But I became consumed with awards, and I came to a point where I had all these awards but I didn’t know whether I was doing something that was glorifying God.

In my exploration of Chef André, I found out that there is a lot more (to life) than awards. And I felt that this was a story, not just for me to explore, but also for a lot of people who had that sense of: What if I don’t get awards? Or I don’t do well in school? Or I am not recognised in the industry?

So redefining success and perfection became the central theme of the film.

You chose to highlight mundane things – stirring the pot, walking the dog, getting a haircut.

When you want to really understand someone, you have to look at the parts that are the most mundane, the unseen parts. It’s the same as God looking at your integrity, what you do when no-one’s looking.

It was actually in that mundaneness that audiences could connect with Chef as well, someone who has achieved a lot. At the end of the day we are all human beings, we are all given talents. But why is it that we are so compelled to compare, and envy other people, saying: Aiyah I can never be like him lah.

I wanted to celebrate the mundane, I wanted to celebrate the humanness of who he is – someone just like us.

What guided your choice to feature the “ordinary” people around him rather than Michelin chefs or reknowned critics?

You know the term “self-made man”? If you dive in deeper, there’s no such thing as a self-made man.

There are people who work very hard to reach a certain standard. And that’s kudos to them. But I think you have to always recognise the different elements that are around you spiritually, emotionally and relationally.

With the film crew, Chef André (in white), and André’s mentor, Michelin three-starred chef Jacques Pourcel (3rd from left). Presenting the finished film to Chef André for the first time felt as nerve-wracking as Chef André presenting his food to Chef Jacques, says Josiah with a laugh.

That’s why it’s a film not just about Chef André, it’s about the people around him as well – for instance his mother. One of the themes in the film is going back to one’s roots. It’s about honouring the starting point of where you came from.

We were very sure that we wanted to feature his mum, because she was someone who had inspired him in his culinary career.

Chef takes staff who are inexperienced, “pure”, and trains them up. Is this an ethic you want to show?

Yes. What are the values that are important at the end of the day? Is your talent just for yourself, your own glory? Or is it for the growth of others as well?

Chef has come to a place where he has recognised that love trumps all. And he’s using his talents to love other people, to build up the younger generation.

In terms of his talent, he has rejected the fact that it’s about him. He’s rejected the fact that it’s about his awards.

There is a point in the film where he says: “It’s not about André any more, it’s about André’s brigade.”

The film is as much about personal history and destiny as it is about a restaurant and chef. How would you describe your own personal history and destiny?

After Ngee Ann Poly, I fell into a certain loop where I was questioning whether I was worthy of the awards and recognition. When I went to the army, I was so tired of film, so tired of the burden of having to deliver the next masterpiece, I didn’t want to touch a camera.

“Six months later, one of my family members committed suicide. I had his CNY footage in my camera.”

But I couldn’t run away from it. One Chinese New Year, I was prompted to pick up a simple SLR to film our Chinese New Year reunion dinner.

Six months later, one of my family members committed suicide. And I actually had his footage in my camera.

My family was grieving, trying to understand why this happened. And I found myself at a place where I could only express myself through film. So I used the footage that I recorded, and I wrote a letter to my family members saying that when we meet each other – some of us only once a year – sometimes we take for granted the fact that we are all okay. I just needed to tell my family members that I loved them.

My cousins actually told me that, through the film, they recognised the beauty of the life that my family member had gone through. And it created a sort of closure for them.

So that was the film that made me recognise that my talents, this blessing that God has given me, isn’t for myself. It is a way of expression and communication to bless other people.

What else came out of this turning point?

I started a few social initiatives, one of which is While You were Sleeping.

I was in university then and, you know university in Singapore, we’re all very gung-ho, study until very late, then sometimes sleep in the school library.

Josiah, with wife Tricia and son Tyler on holiday in Vietnam in 2019. The couple met while working on different social initiatives at university.

People were saying the next generation of Singaporeans is very selfish, we only look out for ourselves. One of my classmates said books were being stolen from the library, so that other people couldn’t get an ‘A’.

“It affirmed to me that the talent God has given me is not for myself. It’s meant to love others.”

I wanted to reject this thinking. So a couple of friends and I decided we want to tell people that kindness lives on even in our pressurising environment.

So we went to students who were so tired they fell asleep at their desks. And we put snacks or canned drinks there, and cards to say that: While you’re sleeping, someone cared for you. Jiayou!

We decided to film this to encourage other people to do the same thing. The movement kind of caught on and even went to different countries.

We were encouraged by people who wrote in to say: Hey, we saw your clip doing this and we were encouraged to do the same thing.

Again it affirmed to me that the talent God has given me is not for myself. It’s meant to love other people.

Was it difficult to work with Chef, who has a reputation for being OCD?

Many people asked me – Chef being such an OCD person, did he change a lot of things in the film?

Contrary to what people thought an “OCD” Chef André would do, he “didn’t change anything” upon seeing the film for the first time. “He respected the crew for their artistic sensibilities,” says an appreciative Josiah.

You know, after the filming process, Chef didn’t really follow up. I don’t think he even realised it was going to be a feature film in the theatres; he probably thought that this was going to be a Youtube video, five minutes, six minutes tops.

When we presented Chef with the film for the very first time, that was a very scary moment. If he hated it, if he felt it was too draggy, if he said: “Why you make me like that?” Then we wouldn’t be able to release it, and all our effort would be wasted.

But when we presented it to him … he didn’t change anything! The only thing he said was: “Oh this shot can see my house. I’m very scared people come to my house!” So we changed one or two shots. Other than that, he respected the crew for their artistic sensibilities.

The film was no. 1 at the Taiwan box office in 2020. What feedback meant the most to you?

We didn’t expect such a reception. No producer or filmmaker would be able to manufacture such a result during Covid – for some divine reason, the next phase of Chef’s story is in Taiwan.

“What God is doing through the film” is beyond what any production crew could possibly manufacture, says Josiah.

Three years ago, I did not know this until I started documenting his story. Three years later, Covid hit. You have Hollywood films that are being delayed – even a global franchise like James Bond. So for us to be able to release a local film during the pandemic and still be no.1 in the box office is something that makes you sit up and ask why. So from the secular lens it’s: “Wah you all very lucky, eh!” But I choose to believe there has been divine intervention.

“Because of the pandemic, people were thirsty for stories of hope.”

I joke that if Chef André had been a Thai chef or a Hong Kong chef, the film would have flopped in the box office, because there was no-one going to the theatres. But because it was Taiwan, and Taiwan at that point in time was dealing with the pandemic quite well – and at the same time because of the pandemic people were thirsty for stories of hope – our film came quite nicely to fill that gap.

I was very touched when someone told me that, over the last year, he had been losing a lot of things – his job, his sense of himself, his sense of purpose – but because of the film, he found what he had lost in the pandemic.

And I was thinking: Wow, if you can get that through the film … It’s not me, you know. In fact, it’s not even the film. It’s what God is doing through the film.

In the film, the olive tree is significant. What is your olive tree?

The olive tree for Chef André was something that reminded him of his past in France.

If you were to ask me about where I came from, I’m reminded about a wall.

With son Tyler, 4. Father and son share a love of Bible stories, which they read together at bedtime.

Since young I’ve had a bad habit of drawing on walls. That caused a lot of grief to my parents. They later taught me to draw on my own wall, and not other people’s walls.

One-month-old son, Jonas, was born “around the same time as the film”, says Josiah. “With two ‘babies’, lack of sleep is a very real thing! But my wife is amazing.”

There was a point in time when I was challenged by God to dream three big dreams.

On my bedroom wall the three dreams I was challenged to write were: 1) Be a children’s pastor, 2) keep making great films that spread Kingdom values, 3) start a foundation.

So I think my olive tree is that wall to keep me grounded, to make sure that I keep focused in terms of the decisions I make.

Where did your love of stories come from?

I was very impacted as a young boy hearing Bible stories in Sunday school.

They directed me to God, who He is. That resonance has lasted since then.

As we grow up as adults, we are also very connected to stories. And I think it’s important for a lot more Christian storytellers to rise up.

The Bible is one huge story book, a series of letters to us, written by God.

It’s a love story that God has given us: The fact that we are sinners, and He has still chosen to love us. So I’m inspired by that.

Who have been your greatest influencers as a Christian filmmaker?

My parents are very firm believers and since young they committed me and my older brother to God. When we were young, my dad had to work overseas, and I remember my mum, a housewife then, had to lug me and my brother to church alone.

At that time we didn’t have a car. And I think her commitment to her faith inspired me and my brother. But, as with many second-generation Christians, there was a time when we took our faith for granted and we were going to church because our mum said so.

Josiah with his parents on his Ngee Ann Poly graduation day in 2008.

But my pastors made sure we recognised the importance of having a personal relationship with Jesus. So I think I was discipled quite well in Sunday School, and I saw the impact of really training a child up in the way he should go so that he wouldn’t steer away from it.

Before I even enrolled in film school in Poly, my pastors and cell leaders and parents were covering me in prayer, to give me wisdom on what to do next.

I was challenged one day in church to “speak the language of the next generation”. But what’s the language of the next generation?

The film crew enjoying dinner with Chef André and Chef’s mother during filming in Taiwan. “Seeing Chef interacting with his mother, you see a more human side of him,” says Josiah. “You really see that love, respect and appreciation. It made me think of my parents a lot.”

There was a revelation that the language of the next generation is the media and videos.

If you can speak the language, then you can have a conversation with them, then you can really touch them. If I don’t speak your language, how am I supposed to convince you that God is great, that He’s created all of us and He sent Jesus down to die for our sins? So there needed to be a certain practice and fluency in that language. Which is why I went to film school.

Art at the end of the day is about human relationships, it’s about people.

Are there ever conflicts within yourself about certain elements of your documentaries as a Christian filmmaker?

For a documentary, especially, it’s important to let the scenes play out and be authentic to the subjects of the film.

We need to recognise that, in showing certain scenes, we are not encouraging or discouraging a certain practice. If anything, it’s my role as a filmmaker to ask questions as organically as possible.

I suspect the reason fellow believers sometimes feel uncomfortable with certain shots is because they feel that films made by Christians are supposed to be “answers” and some kind of “prescription” to follow.

No! I always joke that films can create a divine experience but they are not the Word of God.

You are a product of your success. Are you also a product of your failures?

Yes definitely. I think failures are something that needs to be expected. But if we view failure as a stepping stone, and a way to challenge our faith sometimes, it actually makes you stronger.

One of the things I’ve learnt is that a lot of people can handle failure quite well. I think not a lot of people can handle success well.

If you were to make a film about your own story, what would that look like?

A highlight reel? Maybe what it would look like is celebrating the low moments that I’ve gone through and recognising that even in those low moments God is there.

So my highlight reel would really be my lowlights!

André and His Olive Tree is now showing in GV cinemas and The Projector.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light