Remembering Rev Henry Khoo, an ambassador of Christ to Changi Prison

K C Vijayan // April 9, 2025, 10:17 am

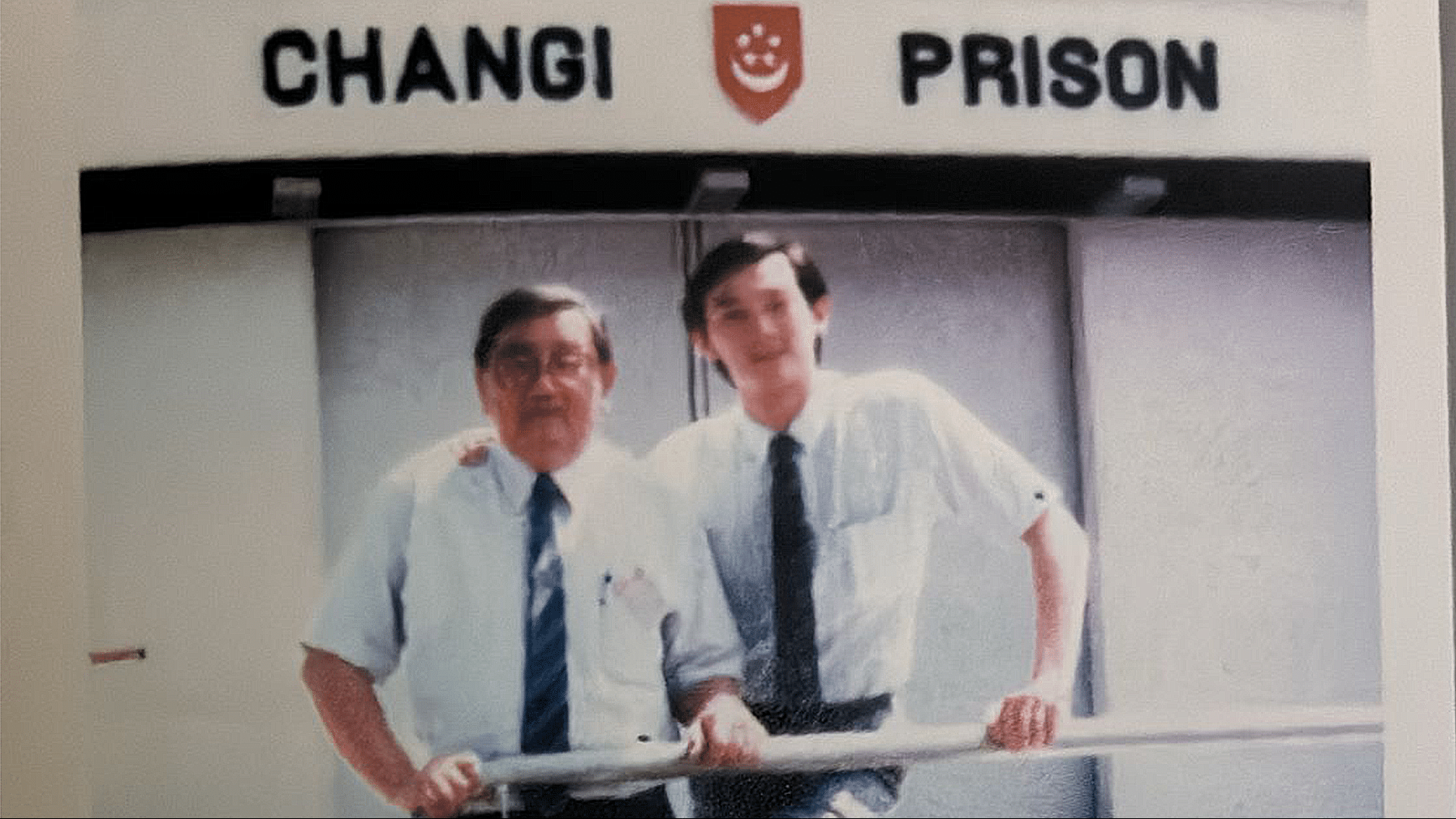

“On numerous occasions I was left speechless in the face of God’s faithful and miraculous interventions,” wrote Rev Henry Khoo (left), with his son, Timothy, of his experience with death row inmates as a prison chaplain. Photo courtesy of Timothy Khoo.

Over the decades, Changi Prison and its littoral jails has drawn many counsellors of various faiths to reach the prison inmates and uplift them to the promise of a new dawn beyond the prison walls.

They include the pioneering Reverend Khoo Siaw Hua, who was the first local Prison Chaplain at Changi Prison, the late Father Brian J Doro and the BBC-heralded Sister M Gerard Fernandez of the Roman Catholic Prison Ministry.

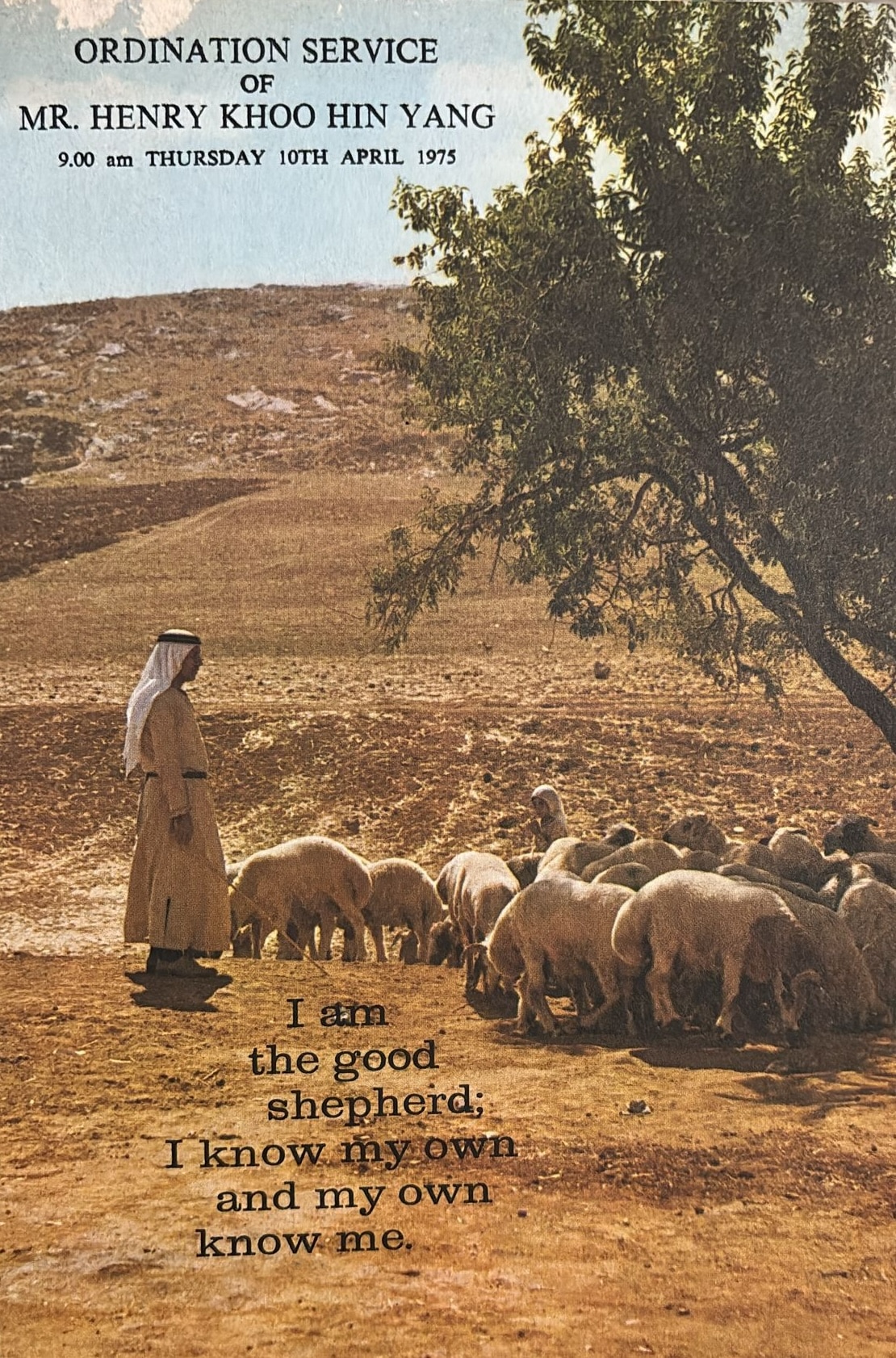

One such person was Rev Henry Khoo Hin Yang, who some 50 years ago on April 10, 1975, was ordained a minister and commissioned associate chaplain at the Changi Prison Chapel.

His service in the prisons bears some reflection on this 50th anniversary of that humble beginning, and his enduring faith in his journey to help turn lives around for nearly 40 years.

Significantly, his job often took him to Changi Prison’s death row to meet scores of inmates over the years. He helped them come to terms with the “state’s penalty for their crimes and help heal the hurt relationships with friends and kin”, as The Straits Times once reported on October 23, 2008.

Following in his father’s footsteps

He started as a teacher at Changi Prison in 1968, and also served as pastor, helping his father, Rev Khoo Siaw Hua, who was the Honorary Prison Chaplain from 1953 to 1985. He later succeeded his father.

Of his father, Rev Khoo himself said in Shoes Too Big, a book he wrote in 2007, that he “grew up in the shadow of a giant” and wondered if he could live up to his father’s legacy.

In his formative years, Rev Khoo said he was “daily touched by my father’s all-consuming single-mindedness in seeking to ‘set the captives free’ – to give them hope that went beyond the prison walls”.

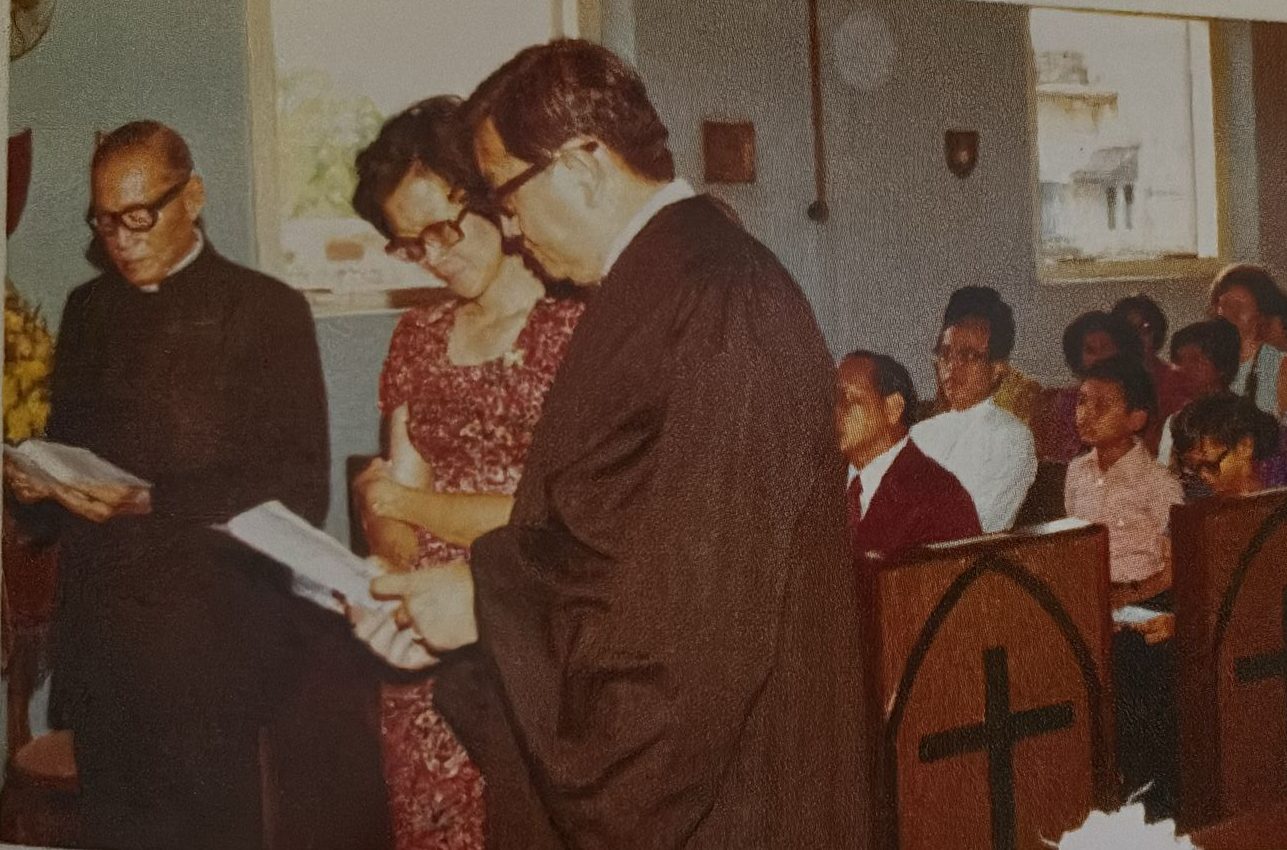

A family photo taken after Rev Khoo’s (left) ordination at the Officers’ club within the prison compound. “Dad‘s ordination was the first time we as kids were allowed into the prison chapel,” recalls his daughter, Ruth Khoo. Photo courtesy of Ruth Khoo.

Rev Khoo recalled the last words his father told him, in halting words, just he drew his last breath in the days before Christmas 1978: “Are the gifts ready? Love the prisoners, care for them, and don’t forget those in the condemned (death) row.”

Rev Khoo said he was overwhelmed “to put it mildly” and often thought of himself as a Jonah in those early days.

But “somewhere deep down, I could sense God’s call. But my human flesh was weak and I thought I could perhaps find other ways to accomplish His will. I did not reckon with the mighty and sure hand of God.” (Shoes Too Big: Henry Khoo, 2007)

Moved by encounters in death row

Rev Khoo’s work and encounters among the prison inmates, including death row inmates, over the years are captured in his book mentioned above.

Two examples are cited here. One was a man sentenced to death over 30 years ago who declined to seek a pardon of clemency from the President although the avenue was open to him.

Rev Khoo at his ordination service on April 10, 1975. Photo courtesy of Timothy Khoo.

Instead, he wrote to the President accepting he deserved to die for the heinous crime he had committed. “I’m not asking for a pardon, but a stay of execution so I can ‘witness’ for my brothers.” He was granted the delay he sought.

Another case in that same decade involved two women, among others, from Hong Kong who were nabbed for drug trafficking, convicted and sentenced to death.

Both were over 18 years old and came from two extreme families. “One was from a dysfunctional home and the other from an over-indulgent one.”

The former was aged four when her parents were separated. She was left with her grandma, but was ill-treated by her uncles and cousins. She ran away at 14, co-habited with a man who used her for ill-gotten gains and was mistreated.

At 18, she ran away to another man who arranged a passport for her and sent her to Thailand to smuggle drugs. She was detected at Changi Airport together with the other girl.

Rev Khoo (third from right) with a group of prison volunteers he led. They used to have attend evening Sunday services at The Salvation Army as they often served in the prisons in the day. Photo courtesy of Prison Fellowship Singapore.

Rev Khoo recalled a Christian counsellor came from Hong Kong and ministered to them during their days in death row.

The girl told Rev Khoo how for the first time she experienced the love of God. “She readily accepted Jesus Christ as her Lord and Saviour and eagerly shared her new found faith at every opportunity,” he wrote in his book.

Rev Khoo vividly remembers the case, and I remembered the anguish and sorrow in his voice when he told me years ago how the girl from the dysfunctional family really “had no chance in life” given her background.

Retired prisons superintendent George Jacob, now in his 80s, recalled how the same inmate never faced him but showed her back during his regular check on such special inmates, who were accommodated separately given their security category. “She knew there was no hope for a reprieve as her appeal had failed.”

But despair disappeared in the face of her newfound faith.

Prison chaplains (from left): Rev Stephen Cheng, Rev Chng Siew Sin, Rev Lorna Khoo, Rev Brenda Lim, Mrs Andy Lim (representing her husband, Major Andy Lim, who was absent), Rev Henry Khoo, Rev Chiu Ming Li, and Rev Kenny Fam. Photo courtesy of Prison Fellowship Singapore.

Rev Khoo recalls in the book that her parents came together to visit her during her final few days.

“On the last visit before her execution, she told her parents that she did not blame them for the present situation she was in. She shared with them the love of God and urged them to accept Jesus Christ as their Lord and Saviour.”

Both sets of parents broke down when they heard the two women sing a hymn to them, but left with some measure of content, seeing how much peace their daughter had, added Rev Khoo in the book.

The bulletin of Rev Khoo’s ordination service on April 10, 1975.

Both he and a female counsellor kept company with them on that final night.

“They thanked the Lord for not only telling them of their homecoming, but also of what awaited them in heaven. As they walked up to the execution chamber, it was clear to all that they did so with the deep peace of God in them.” (Shoes Too Big: Henry Khoo, 2007).

More can be said about the many occasions when he was moved by his encounters and reform that he inspired, than this brief perspective can encapsulate.

“On numerous occasions I was left speechless in the face of God’s faithful and miraculous interventions,” wrote Rev Khoo.

A personal friend

In conclusion, I would point to the beginning and end of my encounters with him in the course of over 30 years and count it my privilege and honour to have known this ambassador of God.

My beginning was to observe his humble ordination service in 1975 at Changi Prison chapel within the prison walls, which was officiated by three Bishops and seven Reverends, the first such congregation to collectively attend the chapel.

They included Bishop Chiu Ban It, the first Asian Bishop of Singapore and Malaya, as the Diocese was then called. Others present included Bishop Chandu Ray, Bishop T R Doraisamy, Rev Yap Un Han, Rev Khoo Siaw Hua and Mr P T Abraham.

Rev Khoo (centre) attending an evening service at The Salvation Army. Photo courtesy of Prison Fellowship Singapore.

The introductory hymn began with the verse: “O master, let me walk with Thee in lowly paths of service free; Tell me thy secret; help me bear the strain of toil, the fret of care.”

The concluding hymn was titled: “Take my life, and let it be consecrated, Lord to Thee.”

The songs and the sermons, along with the lessons and speeches between them, in a way embodied the fervent hope and prayer of a desire to serve with an unfailing faith in the years ahead of him.

Fast forward to some 35 years later, some months before he died in 2008, Reverend Khoo looked me up for lunch and also gifted me a book by C S Lewis titled Mere Christianity.

Rev Khoo (left) with brothers from a Tamil ministry. Photo courtesy of Prison Fellowship Singapore.

He wrote in it: “My friend … May the Lord bless you in all your endeavours.” And he signed his name and added beneath, Romans 5:8.

But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.

I am grateful and feel blessed to have known Rev Khoo. I treasure all the more in this 50th year, the good memories of this ambassador of God.

As Sister M Gerard of the Roman Catholic Prison Ministry once said of him: “You have been a beacon of light and hope to thousands, and many more will follow the example you have shown us. You, Henry, your father and your son, Timothy, have been and are pastors after my own heart.”

RELATED STORIES:

“For God and country”: Chaplains carry on tradition of service and faith

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light