“The Church needs to respond”: Relief Singapore’s Jonathan How on the Rohingya crisis in Cox’s Bazar

In recognition of World Refugee Day on June 20, Salt&Light shines the spotlight on the Rohingya refugee crisis.

by Geraldine Tan // June 20, 2019, 12:02 am

Jonathan How (extreme left) together with Relief Singapore volunteers after a game of badminton with Rohingya youths in Cox's Bazar. He brings volunteers from different faiths to assist with relief efforts in the Asia Pacific region. All photos courtesy of Jonathan How.

It has been raining nonstop for days in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, with more rainfall expected in July when the monsoon season normally peaks.

Laila* sits on a mat in her sparse 10-square-metre shelter, made of plastic tarpaulins wrapped around bamboo frames.

Alleyways in the Rohingya refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar turn slippery and muddy during the monsoon season from June to October.

Her eyes are trained on her three children playing along the muddy pathway outside the tent, meters from a mound of rubbish. The smell of rubbish and sewage hangs heavily in the humid air.

Laila is one of more than 730,000 Rohingya who fled Myanmar in 2017 following the military’s campaign against her people in the country’s western Rakhine state. The United Nations (UN) has denounced the campaign as having “genocidal intent”.

“We saw (refugee) tents as far as the eye can see – tent upon tent, all the way to the horizon.”

Close to a million Rohingya now reside in Bangladesh. Laila lives in the world’s biggest refugee settlement south of Cox’s Bazar, known officially as the Kutupalong-Balukhali settlement.

The settlement stretches across 6,000 acres and has a population density of 60,000 per square kilometre.

“We saw tents as far as the eye can see – tent upon tent, all the way to the horizon,” says Jonathan How, 47, founder and chief executive officer of Relief Singapore (RSG), a homegrown social enterprise and NGO that provides humanitarian assistance and disaster relief for those affected by conflicts, calamities and climate change.

Many politicians who have visited the site commented that the camps are well run and basic needs are being met.

But How, who has visited Cox’s Bazar multiple times since March 2018, begs to differ.

Reality check

“If you visit and you see how they live, the reality is different,” says Jonathan.

The flimsy, makeshift tents are often perched on sandy hills prone to landslides – landslides have already claimed the lives of two Rohingya children in May this year.

But the building of permanent structures is banned, as the Bangladeshi government wants the refugees repatriated as soon as possible.

Tents as far as the eye can see.

The sudden influx of refugees has also taken a toll on the environment as camps were hastily set up to house them.

How recounted his first visit, where he was greeted by pools of fetid water filled with rubbish, and young children defecating openly along the pathways.

Recent visits have not shown improvements – local community leaders tell him that waste management in the camps is still lacking.

A lack of proper waste management in the refugee camp is a public health hazard – the waste has started to contaminate shallow water sources in Cox’s Bazar.

If this situation continues, the waste will slowly pollute the water table, particularly for shallow wells. Already, much of the water is contaminated, notes How. This has led to many Rohingya to suffer from skin conditions.

To address the contamination issue, RSG has helped install water filtration systems and is mobilising more dermatologists to go on medical missions to Cox’s Bazar.

But much more needs to be done.

Man does not live by bread alone

Beyond meeting physical needs, there is also an urgent need to address the trauma that the community experienced as they fled the violence in Rakhine. In addition, there is life in limbo to contend with – adult refugees have little to no work opportunities.

The desperation has resulted in many vulnerable Rohingya refugees being recruited as drug mules to carry yaba, or “crazy medicine”, a popular methamphetamine pill, from Myanmar into Bangladesh.

“Mental health is a pressing need,” adds How. But he concedes that NGOs are unlikely to set up specialised mental health facilities due to the stigma, “so they have to be more creative”.

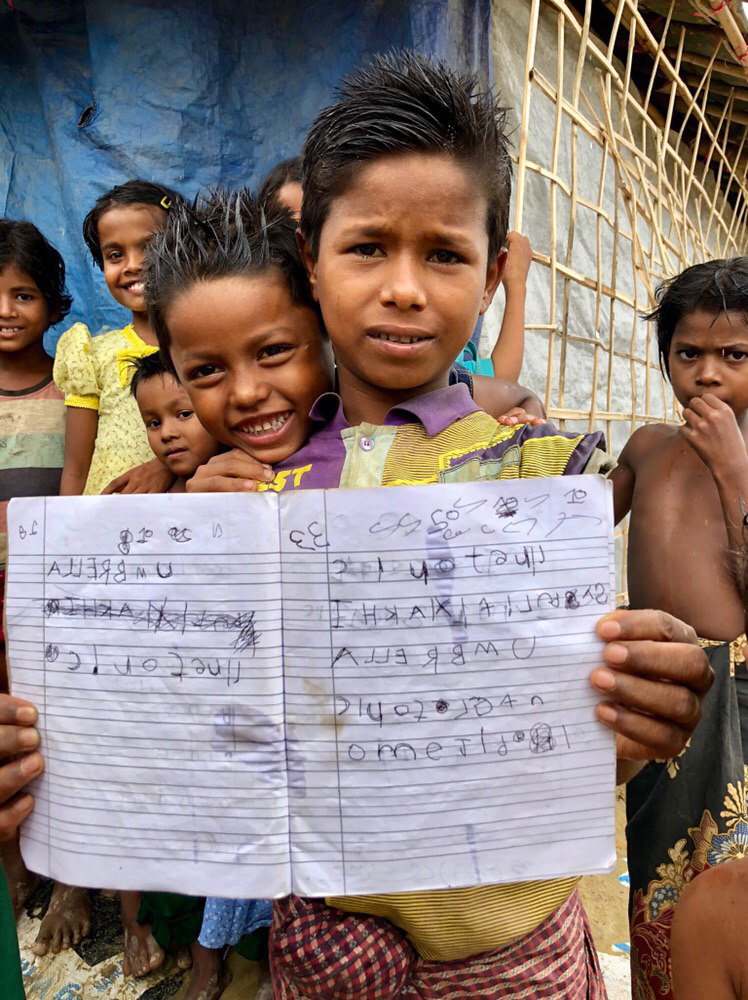

Rohingya children showing their work from learning centres set up by aid agencies in Cox’s Bazar.

Another pressing need is education for the young. Children make up almost half of the refugee population, yet there is no formal education for them. They are not allowed to attend local schools and are forbidden to learn the local Bengali language as Bangladeshi officials do not want the children settling in.

Although UNICEF and other aid agencies have set up learning centres, the quality of education is poor.

Many of the children How has encountered are only able to manage the simple greeting of “Hello, how are you?” and are unable to go further.

Vulnerable females

Gender-based violence is also common. According to World Vision, many girls suffer from neglect, abuse, exploitation, or sexual violence, with hundreds of incidents reported weekly in the Kutupalong-Balukhali settlement, where nearly 650,000 Rohingya live. This is more than twice the size of the next-biggest refugee camp in Uganda.

“But it is hard for justice to be meted out because the (legal) system is not really in place in the camps,” says How. Many of the Rohingya are also distrustful of local authorities, a result of discrimination in Myanmar.

In response to violence against females, Rohingya families are resorting to child labour and child marriage to “keep their daughters safe”.

Many Rohingya women suffer from neglect, abuse, exploitation, or sexual violence, with hundreds of incidents reported weekly in the Kutupalong-Balukhali settlement.

Relief Singapore is currently considering a collaboration with UNFPA, the UN agency for women and children, to organise healthy sports activities.

How has organised mission trips to provide psychosocial support, where the team conducts sports activities for children.

“We are trying to make the programme more sustainable by training the locals to organise the activities themselves,” he adds.

A Relief Singapore volunteer playing a round of mini table tennis with Rohingya youths.

“One of the people we are collaborating with is a specialist in adolescence sexual and reproductive health. The girls get married off early – as early as 14, 15 years old – and they start having children soon after, which is way too early,” explains How.

UNFPA encourages births only after the age of 20, as complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among adolescent girls aged 15-19 globally.

“It is a big challenge to change this mindset because you need to talk to the men, the women. It’s a cultural thing; it is the families wanting to marry them off, for one thing because there’s money involved. So there are a lot of issues when dealing with this,” he says.

Healing the hurts

The Myanmar government believes the solution lies in economic development in Rakhine, prompting its leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, to headline an investment fair in the restive region in February 2019.

She had urged investors from Japan, South Korea and other Asian nations to pour their money into Rakhine.

But How disagrees. “Development does help to bring up economic conditions but alone, it will not help.

“You can have skyscrapers one day in Sittwe, the capital of Rakhine, but it is still not going to heal the hurts … you still need to build peace, you still need to serve justice.”

The healing will not take place overnight and could possibly take decades, he says.

Jonathan (standing, extreme right) with Relief Singapore volunteers and Rohingya youths after a session of sports and music.

“It’s a spiritual problem – and a spiritual problem needs a spiritual solution.”

The needs of the displaced Rohingya are enormous but “we need to remember that we don’t do things on our own strength. We need God to move,” he says, citing Philippians 2:13.

He will be starting a monthly prayer meeting to gather Christians in Singapore to pray over the Rohingya crisis. He believes this “could be the start of the Singapore Church praying for God to move hearts in Yangon and Rakhine”.

He also hopes that the prayer groups can be a meeting point and a coordinating body of sorts, so that the wider church body is “aware of who’s doing what … and better still, collaborate somehow” so that we may defend the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and love the foreigners residing among us, giving them food and clothing”. (Deuteronomy 10:18)

*Name has been changed to protect her identity.

“The Church needs to respond”: Relief Singapore’s Jonathan How on the Rohingya crisis in Cox’s Bazar

How you can help

RSG began providing humanitarian assistance for the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar from May 2018 with the installation of water filtration systems to provide safe water at primary health centres in the camps, in collaboration with the Directorate General of Health Services, Swiss Red Cross, Bangladesh Red Crescent Society and Dhaka Community Hospital Trust.

They now seek medical volunteers to support the HOPE Field Hospital for Women, the only field hospital run by a local Bangladeshi NGO that provides critical healthcare for the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar.

To sponsor or volunteer with Relief Singapore, contact them here.

If you would like to join Jonathan How and others to pray over the Rohingya crisis, sign up here.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light