We can now digitally resurrect anyone, but should we? The moral and theological issues behind cybernetic reanimation and digital necromancy

Rev Dr Lorna Khoo // April 1, 2025, 2:02 pm

The technology now exists for people to "raise the dead" using AI to render the likeness of someone who has passed away. AI-generated image by Rev Dr Lorna Khoo using Meta AI

Imagine…

You attend a funeral. You know that your your departed friend did not do a pre-recorded video of himself giving a speech for that occasion. Yet you see him on screen as an avatar, speaking with a voice that sounds like his, addressing everyone there, thanking all for attending the service.

You watch a recently produced movie and you see a long deceased actor appear in several scenes.

You are able to dialogue with a daughter who died some time ago as you view her avatar on screen. She is able to answer your immediate questions as if she was still alive.

Are the above imaginary happenings from a science fiction movie? Or perhaps a prediction of future possibilities?

No.

The technology to make them real is already here.

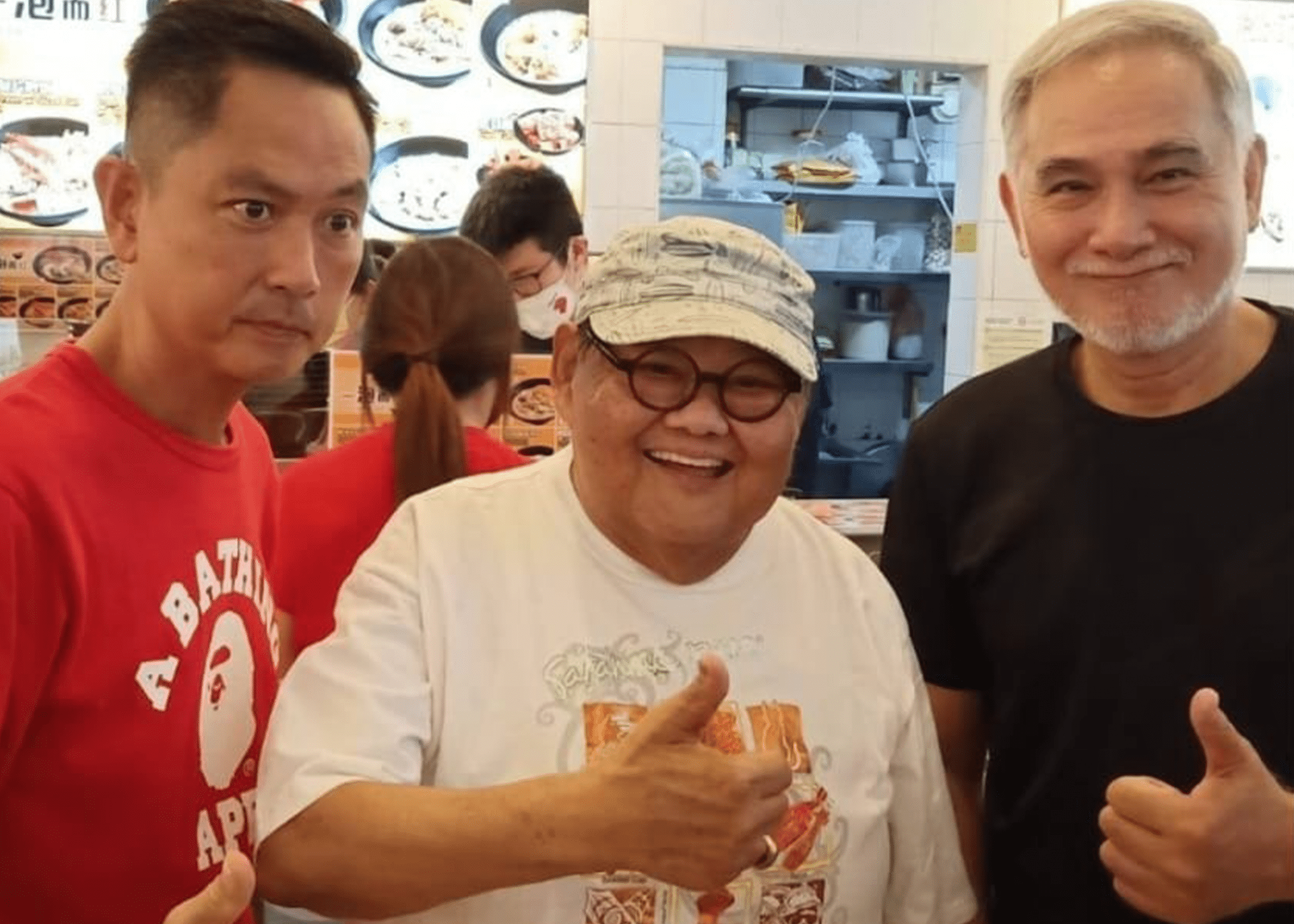

When beloved comedian Moses Lim passed away, he was seen addressing those who attended his funeral in an AI-created video. His voice was digitally-generated and the clip showed his likeness addressing viewers in Mandarin.

This AI-generated likeness of Moses greeted those that attended his funeral in February. The video was put together by close friends with his family’s approval.

If you watched the movie Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016), you would have seen the late British actor Peter Cushing reappearing as Grand Moff Tarkin, a role he played in earlier the first Star Wars movie A New Hope (1977) before passing away in 1994.

The Straits Times (November 22, 2024) reported that “Undertakers in China use AI to allow people to communicate with their deceased loved ones”: “With just a photo, a voice recording and machine learning, undertakers in China are able to use artificial intelligence to create life like avatars of people who have died, allowing their loved ones to ‘communicate with them’. What is created is able to ‘mimic the deceased personality, appearance, voice, and even memories to allow people to relive moments with their loved ones who have departed the living world …”

Cybernetic reanimation: Good or bad?

This is known as cybernetic reanimation: The process where AI brings deceased people back in digital form. It is done by algorithms trained to analyse the individual’s digital footprint (online videos, emails, photos) and using tools like generative AI (such as ChatGPT) and image and video generators (like DALL-E2) to recreate them.

While CGI technology has already made it possible to de-age actors (for example in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny), this new technology goes even further, allowing “resurrections” of sorts. And yes, it’s already happening.

The real Harrison Ford (right) in Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny and his “de-aged”, computer-generated likeness (left).

It can be argued that there are some positives in such developments, such as:

- It gives extended time for emotional closure after a death ie when grief issues are still very raw

- It preserves memories in an interactive way

- It injects creativity in education eg having an avatar of Alexander the Great regale his conquests would be more engaging than reading it in a history book.

- Financial harvest can be reaped by actors for future appearances in movies, as Singapore actor Gurmit Singh expressed.

But we need to ask these questions: What are the possible dangers posed by digital resurrection? What does the Bible say? How should we, as Christians, respond to cybernetic reanimation?

Possible dangers of “digital resurrection”

1. Accuracy of depiction of the person, particularly when it is presented as a first person account

To begin, information from third-party sources might not be true of the actual person. There may be cultural or historical bias in the re-telling of his or her story. Photographs, videos, letters, emails, WhatsApp messages, Instagram posts, etc, are not direct representations of our loved ones. They serve as conduits to their memories, not channels to their very being or communication.

While a digital resurrection may present a person’s conscious self, it cannot capture their unconscious self. Resourceful individuals might design an idealised version of themselves, which distorts personal narratives, presenting a version that is not authentic.

2. Maintaining the integrity of the deceased’s real personhood

A digital resurrection can only provide an incomplete representation of a deceased person, turning them into a “zombified version” or “functional ghost”.

Interacting with a zombified version and forcing it to comment on contemporary world issues or cultural situations can be problematic. The individual, based on a specific cultural background and historical timeframe, would not have the integrity or understanding to do so.

Asking zombified figures like Moses to comment on the current Gaza war would be anachronistic or even blasphemous.

For example, asking figures like Moses or Joshua to comment on the current Gaza war would be anachronistic and could be seen as disrespectful or even blasphemous, especially when dealing with religious figures.

One can conjure up an image of Moses (during the plagues in Exodus 7-11) but it’s not the real person of Moses. Images from @theaibibleofficial on Instagram.

3. Respect for the decisions of the deceased or his family

When consent is not given by the person or authorised by their relatives, ethical and legal issues of identity theft and abuse can take place. There could be risk of commercialisation and exploitation of someone’s identity.

If digital resurrection allows for communication or inappropriate relationships with the deceased, it raises issues of trust, desecration, and disrespect for the person’s memory and legacy. It can also undermine the real intimacy they once had with loved ones.

Digital resurrection may allow for communication or inappropriate relationships with the deceased.

The reputation of the deceased may also be affected. There was a digital recreation of Bruce Lee endorsing a drink in an advertisement which completely ignored the fact that Bruce Lee never drank in real life.

4. Moral and financial issues

It raises the question of “ownership” as well: Who owns the digital assets and the digitally resurrected icons (sometimes referred to as ‘delebs’) of the dead person? If the digital assets are not clearly willed by the person prior to his death, this becomes an issue. Does the person become a “ghost” slave of their descendants or a company?

While some living actors view the possibility of “living and working on after passing” as a bankable option — that is, they can sell the rights to their image before they die — some, like the late Robin Williams, have placed some limitations on such possibilities. Robin Williams signed a deed to prevent his image, or any likeness of him, being used at least 25 years after his death.

5. Reality could be compromised

With cybernetic reanimation, the line between the living and the deceased is blurred. This may contribute to more mental health issues for those already afflicted with emotional challenges.

6. Delaying healthy grief work

The acceptance of loss and adjustment to life without the physical presence of the loved one may be delayed. A deathbod (a chatbot that imitates the behaviour and conversation of the dead) may keep the bereaved from moving on in life and creating new relationships (for example, remarrying).

7. Theological and pastoral issues

Humans created by God in His image have unique identities and dignity in Him. The creating of an AI replica and setting it up for communication purposes between the living and the dead dishonours the actual deceased person. In some situations, it can make an eternal idol of an inaccurate or fake identity of the person.

Creating an AI replica and setting it up for communication between the living and the dead dishonours the actual deceased person.

In providing a way to avoid the pain of grief from death, it will remove the pressing urgency of humans to reflect more deeply about one’s mortality and eternity.

Scriptural and theological problems posed by digital resurrection

1. Bearing false witness

It is impossible to create an exact replica of the deceased because we can never access their unconscious self. When digital resurrection is presented as a first-person account, and the living interact with the digital character as though it were the actual person, it perpetuates a falsehood. The digital character is not the deceased — it is bearing false witness against the person (Exodus 20:16).

2. Hurting the good name of the deceased

Proverbs 22:1 says, “A good name is more desirable than great riches; to be esteemed is better than silver or gold.” (Ecclesiastes 7:1) Depicting the deceased in a way that does not reflect their true character and values — like the AI Bruce Lee alcohol ad — disrespects the deceased, their memory and their legacy. It damages their good name, their reputation.

This whisky advertisement digitally resurrected the late Bruce Lee, completely ignoring the fact the actual person of Bruce Lee did not drink.

c. “Stealing” the person of the deceased

Exodus 21:16 says: “Whoever steals a man and sells him, and anyone found in possession of him, shall be put to death.” While this refers to physical slavery, the principle applies to digital resurrection. Treating a person’s identity as a commodity without their consent is a form of exploitation. Just payment is required for labour done (1 Timothy 5:18). When the digital likeness of a person is used for profit without the consent of the person or their family, it is stealing. Stealing is a sin (Exodus 20:15).

d. Avoiding one’s mortality, the reality of death, hell and heaven

“O Lord, make me know my end and what is the measure of my days; let me know how fleeting I am! Behold, you have made my days a few handbreadths, and my lifetime is as nothing before you.” (Psalm 39:4-5) We must acknowledge the brevity of life.

Clinging to digital recreations distorts our perception of reality and denies the natural process of life and death. Engaging with a digital copy of a deceased person can create an illusion, preventing us from facing the reality of our mortality, the coming judgment before the throne of God, and the need for repentance. “And as it is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment…” (Hebrews 9:27)

An AI replica cannot capture the unique soul and identity given by God.

It also anchors us only to this dimension of life and distracts us from the glory that is to come. Those who belong to Christ will enter into everlasting life, made whole by Him, enjoying His presence, and receiving the rewards promised by grace to the faithful (Romans 8:18-21, Revelation 21:1-7).

e. Bypassing grief

God gave us tear ducts. As there is a season for everything, there is a “time for mourning” (Ecclesiastes 3:1, 4). This time should not be artificially prolonged or avoided through digital means. As Christians, we grieve with hope, unlike others who do not have the hope of life beyond this dimension (1 Thessalonians 4:13). Prolonged attachment to an artificial version of a loved one will interfere with the natural healing process and impede the need to move forward in life.

f. Devaluing the dignity of one made in God’s image

We are created in God’s image (Genesis 1:27). An AI replica cannot capture the unique soul and identity given by God.

When a digital copy is treated like a real person, it devalues the humanity of one made in God’s image. Worse, this copy can become an idol.

When great reverence is given to the digital character, for example, seeking its desires and fulfilling them, it is akin to treating it as an idol. God forbids this in Exodus 20:4-5: “You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them.”

g. Fake Christ and the dark side

Replika, another AI platform, has made it possible for people to dialogue in real with “digital versions” of historical figures such as Napoleon, and even Jesus. But it is not the real Jesus.

Even if the algorithm draws from only Biblical records, it will still need input from scholars regarding historical backgrounds, context of the narratives, hermeneutics and more. The Jesus depicted will speak according to the sources used – whether conservative or liberal interpretations – but it will not be the real and living Christ.

This is forbidden territory: Scripture specifically forbids communication with those who have passed into eternity (Leviticus 19:31; Leviticus 20:6, 27; Deuteronomy 18:10-13; Isaiah 8:19-20).

Scripture specifically forbids communication with those who have passed into eternity.

Doing so opens the door for the dark side to attack. Movies like Pet Sematary (1989), Flatliners (1990), and The Lazarus Effect (2015) portray the unpredictable dangers of attempting to breach the boundaries between life and death. The act of raising the deceased through digital means can invite spiritual dangers. By disregarding biblical teachings, individuals may inadvertently open a door to demonic influence, giving the enemy legal grounds to deceive, oppress and harm the living.

How should we, as Christians, respond to cybernetic reanimation?

a. We need to differentiate cybernetic reanimation from digital necromancy

Cybernetic reanimation is using AI to bring back likenesses of the deceased for entertainment, education or remembrance. Digital necromancy is where AI allows real time interaction with the dead.

The key difference is that in digital necromancy, there is dialogue and interaction taking place.

Humans want to remember and commemorate their loved ones. We already seek to let the dead “live on” through images, videos, relics, heirlooms, audio recordings. But these modes (even cybernetic reanimation in some cases) are different from digital necromancy.

The key difference is that in digital necromancy, there is dialogue and interaction taking place. The deceased is “resurrected” by AI to be related to as if it is a live person dialoguing with the living in real time.

Cybernetic reanimation is fairly neutral in some areas. In the case of the AI clip of Moses Lim addressing his mourners, it

- was produced by close friends with permission from his family,

- reflected accurately his character and spirit,

- was akin to pre-recorded videos and

- was accepted by all as “not the real Moses”

- did not offer two-way communication with the AI Moses

Digital necromancy is dangerous and Christians should be warned against engaging in it.

b. The approach to each would need to be different

The practice of cyber reanimation (the technique and practice) raises the need to have proper regulations protecting legal ownership/rights to and moral use of digital assets.

One’s will for example, would need to dictate who inherits one’s digital footprints and what one allows to be done with it. The Church would do well in educating her members about this and encouraging those in digital and legal professions to develop regulations that will protect all from questionable or immoral use of digital inheritance.

The pastoral (eg, grief issues), theological and spiritual concerns are very real when it comes to digital necromancy. Clear Biblical teaching is necessary on the subject of communicating with the dead, especially in light of God’s command that forbids it.

The pastoral, theological and spiritual concerns are very real when it comes to digital necromancy.

The consequences of disobedience must be clearly outlined. Those in the counselling profession and seminaries need to start preparing the helping ministries to advise and handle consequences that may arise from engagement in digital necromancy. This would also include training in deliverance ministries.

NOTE: This short writeup is not comprehensive. It simply seeks to introduce to all the existence of the technique and practice of cyber reanimation and list the possible issues that may arise from it, especially the dangers of digital necromancy.

As one who is involved in inner healing, I am raising this matter in hope that more thought, research and discussion will be sparked by this article on the topic.

RESOURCES

- “‘Digital Necromancy’: Why bringing people back from the dead with AI is just an extension of our grieving practices” by Jo Adetunji, The Conversation, UK, September 19, 2023

- “Beyond Peak Death? The Advent of Digital Necromancy and Functional Ghost” by Axel Gruvæus, Journal of Futures Studies, 2023

- Life, death, and AI: Exploring digital necromancy in popular culture —Ethical considerations, technological limitations, and the pet cemetery conundrum by James Hutson and Jay Ratican, Lindenwood University, 2023

- “Digital Life after Death: Grief Tech or Digital Necromancy?” by Dave Betts, The Church and AI, Sept 1, 2023

- “Would you want to live on as an AI chatbot after you die?” by Patrick van Esch and Yuanyuan Cui, The Straits Times, January 10, 2025

- “Speak to fictional characters reimagine classic tales at NLB’s generative AI nodes” by Sheo Chiong Teng, The Straits Times, January 24, 2025

- Short discussions on the topic with Mr Charis Lim, Chair of DIGITAL WESLEY and Mrs Lai Kheng Pousson.

RELATED STORIES:

They want to expand the global reach of quality Christian content with the help of AI translation

The Bible doesn’t talk about tech and AI, so what should we do?

How a child-like prayer for ducks laid the faith foundation for an AI start-up

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light