“Playing the violin for me is like praying”: One-handed violinist Adrian Anantawan

by Rachel Phua // April 7, 2018, 12:52 am

Adrian Anantawan playing with the Metropolitan Youth Orchestra of Hong Kong in March 2017

The pounding notes of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony echo around the room.

“This is what anger sounds like,” violin virtuoso Adrian Anantawan tells me as he plays vigorously.

He would know. His violin has been his means of expressing emotion ever since he was a child.

“The violin gave me a voice to be able to ‘say’ things to people. It wasn’t about how I looked anymore. It was how I sounded, how I was able to turn my emotions into something.”

Anantawan, 34, was born without a right hand. The likely reason, doctors told his parents, was that the umbilical cord had wrapped itself around his arm in the womb, preventing it from growing properly.

In spite of his disability, the soft-spoken young man with the wide smile is one of the most accomplished violinists in the world, having earned degrees from the Curtis Institute of Music, Yale University and Harvard Graduate School of Education.

One of the youngest members ever to join the National Youth Orchestra of Canada, Anantawan has performed at the White House for then-President George W Bush, for the Dalai Lama and Pope John Paul II. His violin has taken him to the United Nations, and to the opening ceremonies of the Athens and Vancouver Olympic Games.

Yet here he is, on a grey Sunday afternoon, at New Life Community Church in Singapore’s humble Geylang district, talking about how none of this would have been possible without the grace of God.

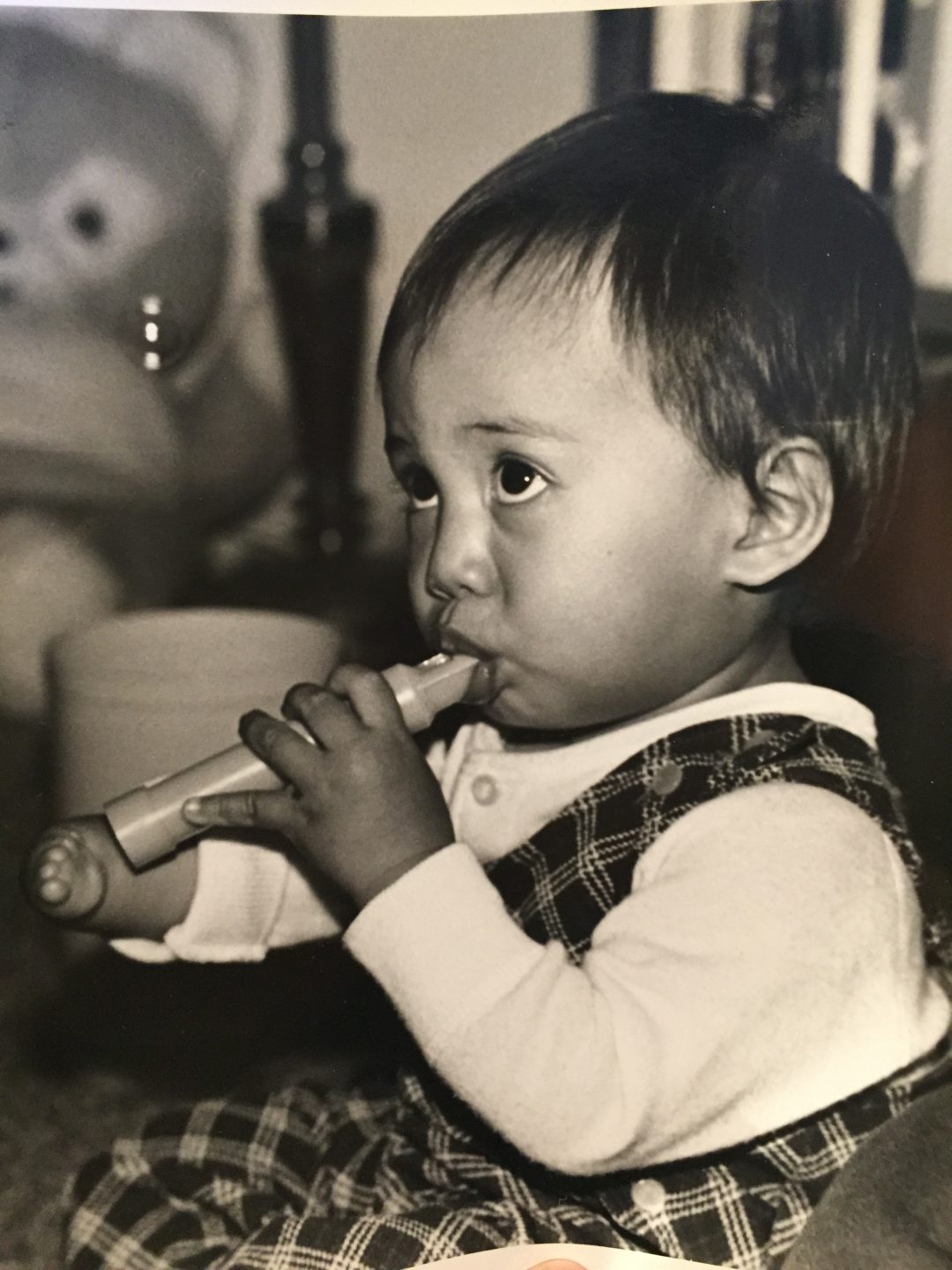

Young Anantawan playing with a toy recorder. Ironically, it was a recorder music class that eventually led Anantawan to pick up the violin at age nine.

“Just fix me”

Born in Ottawa, Canada, to a Thai father and a Chinese mother from Hong Kong, Anantawan was the eldest of three boys. His was a loving family, with Catholic parents who nurtured in him a “can-do” attitude.

His parents were initially worried about presenting him to the grandparents, afraid that they would think “a curse had fallen on our family”. But when his maternal grandmother visited from Hong Kong, she dissolved all their fears.

“My grandmother said that there was nothing wrong with me … she saw me for who I was on the inside, rather than what I was missing,” says Anantawan.

She bought baby Anantawan a toy bracelet with jingles on it. To this day, when he plays the violin, he thinks back to playing with the bells on the bracelet, a reminder of his grandmother’s kindness.

Still, growing up wasn’t plain sailing. As a child, he had difficulty tying his shoelaces, riding a bike, and all the everyday stuff that kids normally pick up with ease.

“The violin gave me a voice to be able to ‘say’ things to people. It wasn’t about how I looked anymore. It was how I sounded.”

In school, he was bullied. Children would kick him and throw rocks at him. He would go home crying, which he found hard to do because he didn’t want to sadden his mother.

It was difficult dragging himself to school every day. Under constant torment, the young boy wanted to “go into the darkness, and just try to protect myself from that fear”.

“I said, ‘If this how people are going to treat other people that are different, why do I want to connect with anyone? Why do I want to have hope and be with other people, try to socialise and try to be kind?’

He admits that he used to blame God in those early years, not for his disability, but the struggles that it created.

“Sometimes I would just cry out at night, ‘Why am I just not good enough? Why do you put these things on my plate? Just fix me.’

“But my parents always told me that God doesn’t put a challenge in front of you that you can’t handle eventually. It took awhile for me to realise what that looks like.”

Leap of faith

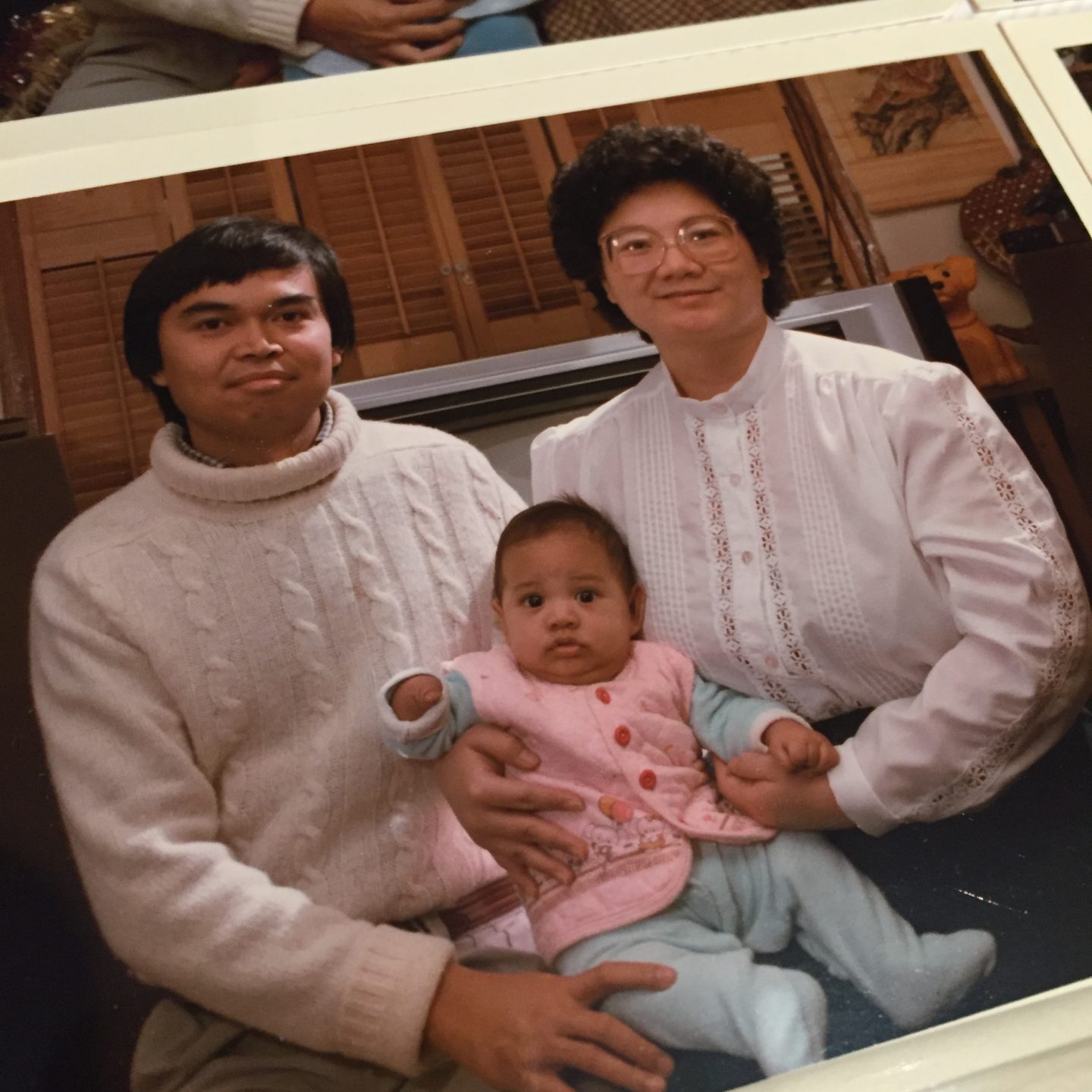

Anantawan as a baby with his Thai father and his mother from Hong Kong.

He first picked up the violin when he was nine.

He and his classmates had to learn how to play the recorder in music class. He was physically unable to, as the instrument had too many holes and he had too few fingers. His teachers told him to just appreciate the music, sit and clap along.

But his parents did not accept that that was the end of his music lessons. They looked for alternatives, starting with the trumpet. It was too loud. Singing wasn’t his forte, his parents concluded quickly. Then they found the violin, which his father had played once upon a time.

“Playing the violin for me is always like praying. It’s a way of showing all of myself, all my fear and joy.”

And, finally, young Anantawan found that, when he played, he was the same as everyone else.

Engineers at a rehabilitation centre designed a device out of plaster, aluminum and Velcro straps, which allowed him to grip the violin bow and play the instrument with delicate nuances. The prosthesis is called a spatula.

It was his mother, he says, who “took a leap a faith” and bought a violin even while his ability was in question.

She told her son: “We will figure it out one step at a time, day by day. If this is something that you want to do, [you won’t be doing it] just by yourself. You are not alone.”

“Sometimes I felt guilty sharing my struggles with her, because I didn’t want to disappoint her or weigh her down, and yet every single time I did, she accepted me more.

“So I think that, if God is love and acceptance, that was something that she practised and it was something that I always need to be reminded of.”

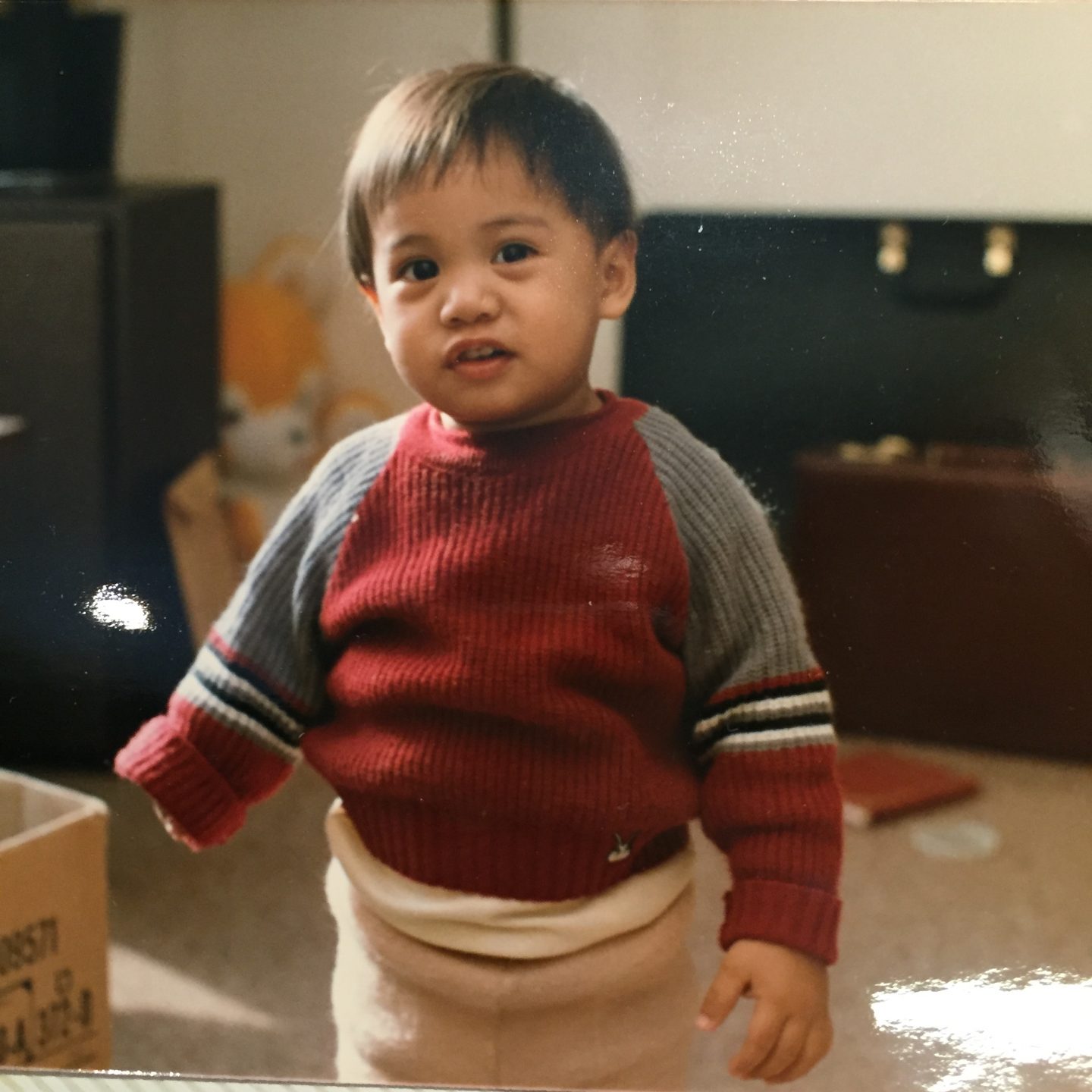

As a child, Anantawan struggled to find acceptance due to his unusual appearance. He was bullied by his peers who taunted him and threw rocks at him.

God’s music

Today the shy young boy with the shaky confidence has grown into a self-assured man who flashes a huge grin ever so often. He’s chatty and unassuming with everyone that comes up to him.

“What’s your favourite Singaporean street food?”

“What’s your journey with Christ like?”

Anantawan says that it was picking up the violin that changed his perspective. He was finally able to understand that all his troubles were a “gift” from God. It developed his empathy and compassion for others. He became closer to the Almighty.

“Playing the violin for me is always like praying. It’s a way of showing all of myself, all my fear and joy,” he says. He also hopes when someone hears him play, they are able to find “aspects of their own struggles” in the music.

Adrian with a prosthetic right arm. Photo by Kenneth Lim.

From performing to teaching

Here to perform alongside world-class artistes with disabilities in the inaugural True Colours Festival, an Asia Pacific festival of music, Anantawan says he doesn’t perform to prove something any more, but to share something.

He fully recognises that his talent is a gift from God. And it is this awareness of God’s providence that has inspired him to move from performing to music education, using adaptive technology to aid aspiring young musicians in overcoming various disabilities.

He helped to create the Virtual Chamber Music Initiative, a cross-collaborative project that had researchers, musicians, doctors and educators develop adaptive musical instruments capable of being played by disabled youths within a chamber music setting.

It is this awareness of God’s providence that has inspired him to move from performing to music education.

Music, for Anantawan, is a great equaliser, and is another avenue for disabled children to express themselves. “Accessibility is not an act of charity,” Adrian said in a TEDx talk. “It’s one of lifting the ceiling of potential development so that all children can explore this world, but also possibly create new ones.

“I think that at a certain point … I [felt] like I was getting too used to just playing and getting approved all the time,” he says.

He wanted to “figure out other ways where people in [a similar] situation [as him] would be able to have music in their lives”.

Backstage during a Metropolitan Youth Orchestra of Hong Kong performance in 2017.

In 2011 he decided to go back to school, studying education at Harvard. Upon graduation, he took the position of music director at the Conservatory Lab Charter School, an elementary school in Boston that serves the city’s low-income students.

In 2016, he moved on to chair the music department at Milton Academy, a school outside Boston, in order to invest more time into advocating for people with special needs.

“Sometimes, kids don’t have their voice to say ‘I can do this’. Or parents don’t have the resources or tools to know that their children with disabilities can play music. [I wanted to help] students find a greater sense of belief in themselves.”

God is in music, believes Anantawan. Which perhaps explains his favourite hymn: Amazing Grace.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light