“No one could help me, my only source of strength was God”: Tortured war heroine Elizabeth Choy

SaltandlLight wishes all women joy, peace and strength on International Women's Day, March 8, 2019.

A/Prof Joseph Thambiah // March 8, 2019, 6:00 am

Elizabeth Choy in 1955, in a photo from the Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

The story of Elizabeth Choy is one of, not just personal courage and the possibilities of an indomitable spirit, but also that of a woman with an abiding trust in God, who was her source of strength in times of extreme adversity and in the presence of profound evil.

Elizabeth Choy was born Yong Su Moi in 1910, in a little settlement called Kudat in British North Borneo (now Sabah).

The Yong family were devout Hakka Christians, having embraced Christianity in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and her grandparents had worked for German missionaries. This fruit was passed through the generations and rested strongly with Su Moi.

She grew up with Kadazans (an ethnic group indigenous to Sabah) and was taught that all work was noble – no matter how menial. She received her early schooling at St Monica’s in Sandakan.

Because of the missionaries’ difficulty with Asian names, the pupils were asked to select from a list of English names. Su Moi chose the name Elizabeth.

Special grace

Life was spartan and the missionaries focused their work on training their students to be good Christian girls.

Her time at St Monica’s had a lasting influence on her life. She remembered Archdeacon Bernard Mercer telling her while at school: “Su Moi, God has given you special graces and you must make use of those graces.”

She went on to study at the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus in Singapore.

The Choys on their wedding day on August 16, 1941. Photo used with the kind permission of the family.

At the age of 20, she had to begin employment to help support the family and became a teacher at the Church of England Zenana Missionary School (later renamed St Margaret’s School), moving on two years later to St Andrew’s Boys’ School in Stamford Road.

“Su Moi, God has given you special graces and you must make use of those graces.”

Canon RKS Adams was principal at the time, and impressed her greatly with his leadership ability and missionary zeal.

On August 16, 1941, at a unique double wedding, Elizabeth married Choy Koon Heng in a well-attended ceremony at St Andrew’s Cathedral, conducted by Archdeacon Graham White and assisted by Canon Adams.

Choy Koon Heng was a book-keeper employed by the Borneo Company. The newly-weds set up house shortly after in Mackenzie Road.

In the days following the Japanese invasion of Malaya, Elizabeth stepped forward to be a volunteer nurse with the Medical Auxiliary Service. When the attack on Singapore began in February 1942, their home was damaged and was quickly looted.

The locals were ordered to report to police stations, where they were subjected to the sook ching, a clean-up operation to screen out anti-Japanese elements. This screening was loosely applied and sometimes could be capriciously based on whether they liked the “look” of the person or not.

Those singled out were taken away and never seen again. Elizabeth’s teenaged brother was one of those secretly massacred.

Seized by the kempeitai

As they had now lost their jobs following the Japanese invasion, the Choys set up a canteen in the Miyako Hospital (the former mental institution), which soon began running regular ambulance services for the internees at Changi Prison.

They courted great risk to their own lives by supplying medicine, money and messages to British civilians interned in Changi Prison. In addition, they also sent into the jail radio parts for hidden receivers on a daily ambulance run.

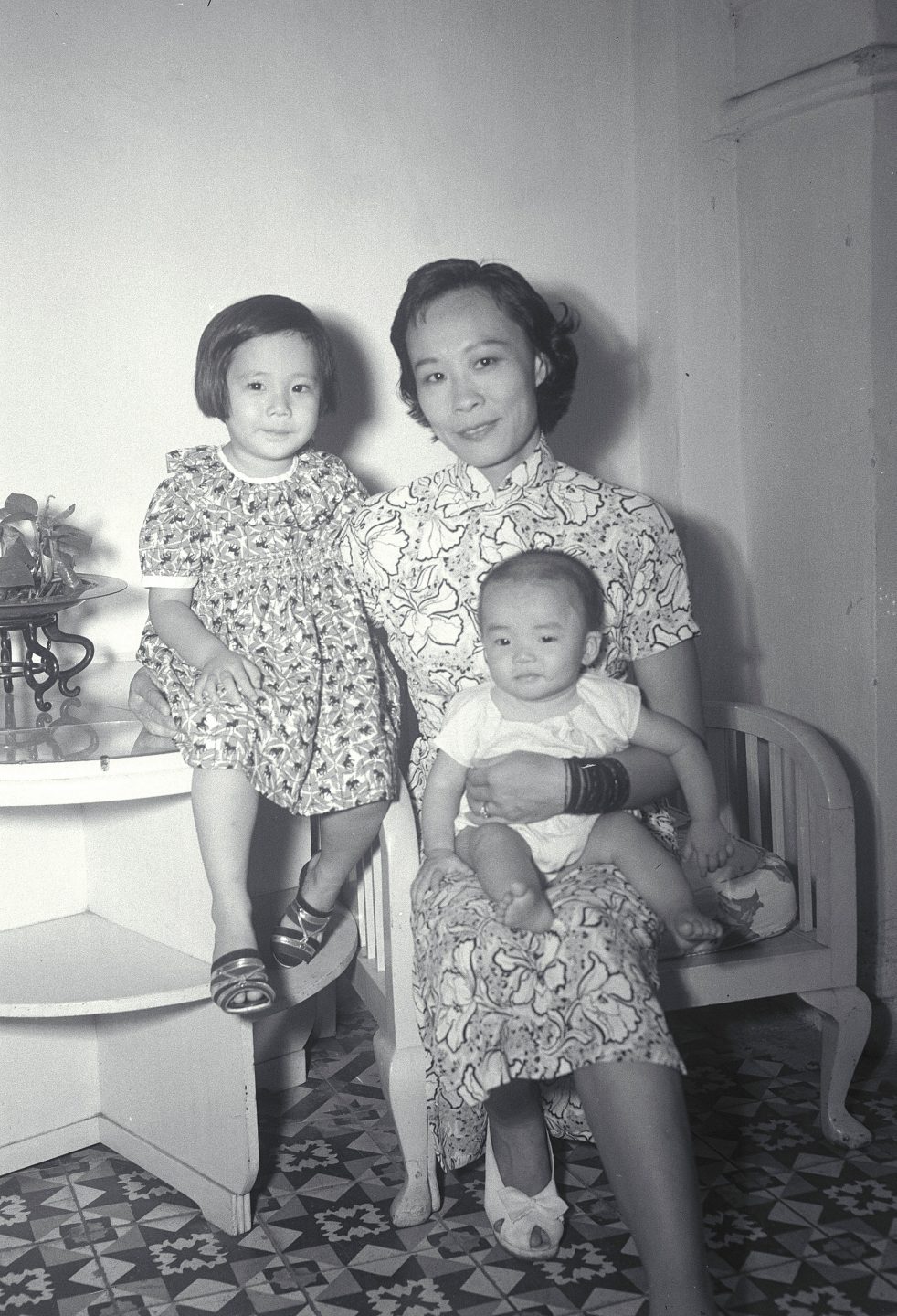

Elizabeth Choy with her children in 1953. Source: The Straits Times, Singapore Press Holdings Limited. Reprinted with permission.

The system appeared to work effectively until September 1943, when a joint Australian-British commando force sank seven Japanese ships in Singapore Harbour.

The kempeitai, suspecting that the raiders had acted on information sent out from Changi Prison by a transmitter, raided the jail and seized 57 internees for interrogation on October 10, 1943 in what became known as the Double Tenth Massacre. Fifteen of these 57 died as a result of their torture and interrogation.

Information obtained as a result of these interrogations led to the arrest of Koon Heng on October 29, 1943, and Elizabeth herself 16 days later.

193 days in prison

She was lured to the kempeitai’s headquarters in the old YMCA building on Stamford Road, on the pretext of being allowed access to see her husband; the Japanese even told her to bring a blanket along for him.

The cell had only a narrow air-vent on one side and no windows. The floor was made of wooden planks, on which the inmates were forced to sit cross-legged all day. There was a single commode, which was also the source for their drinking water. The cell was filthy, damp, gloomy and bug-infested.

Instead, she was seized and thrown into a cramped cell with 20 men. She was the only female.

Elizabeth tried to make life bearable for the others. Obtaining a stone from the guards, she used it to scrub the commode.

This was to be home for Elizabeth for 193 days.

No talking was allowed, but the inmates developed their own sign language to communicate with each other. Every now and then, an inmate would be taken away for interrogation. Some never made it back alive. Sleep was difficult when the stillness of the night was frequently punctuated by the screams of the tortured.

True to her nature, Elizabeth put aside self-pity and tried to make life bearable for the others.

Obtaining a stone from the guards, she used it to scrub the commode. Even a sliver of wood became a precious commodity, passed from one inmate to another to clean their teeth. Food was pitifully inadequate. Bugs were everywhere, feasting on their bodies.

She was slapped, kicked, spat at and subjected to electric shock treatment.

Tortured infront of her husband

On December 9, 1943, in an attempt to extract a confession, this torture was carried out in front of her husband. In his affidavit at the Double Tenth trial on 18 March 1946, Koon Heng described part of that session: “She was tied up with hands and legs to a frame kneeling on firewood. They took out two leads from a generator and applied it to her body for 15 minutes. She was screaming all the time …”

The electric shock treatment was so traumatic that she would not touch any light switches or electrical appliances afterwards.

She was told that she would be taken to Johor and beheaded. Her husband’s head would roll two hours later.

Through all this, she refused to confess. She was steadfast through this terrible ordeal and although she was unable to suppress her screams or the tears streaming down her face, she continued to insist that all she did was merely help those in need. After every session of torture, she always walked with resolution back to her cell.

The only exception was after the session in front of her husband. She tried to walk unaided, but collapsed before she reached her cell.

In that same session and in a final attempt to force a confession, the kempeitai sentenced them both to death. She was told that she would be taken to Johor and beheaded. Her husband’s head would roll two hours later.

They were told to say goodbye to each other. They tearfully and lovingly bade their last farewells to each other.

It turned out, eventually, to be a psychological ploy to break them.

Holy Communion: Burnt rice grains and water

Bishop Wilson was imprisoned in the cell next to hers, and she became determined to be ministered to by him. She volunteered to scrub the floors and when she reached his cell, at a time the sentry was not watching, she knelt down next to the bars of his cell.

Bishop Wilson consecrated some burnt grains of rice and water from the commode and there, in the midst of all that squalor, a grateful and weeping Elizabeth Choy received Holy Communion.

It was a simple act, but one that recharged her spiritually.

Bishop Wilson consecrated some burnt grains of rice and water from the commode and Elizabeth Choy received Holy Communion.

In spite of all the repeated interrogation and torture, Elizabeth’s story never changed. Her story apparently corresponded with those whom she claimed to have helped and eventually, the kempeitai became impressed with her courage and her reputation for selflessness and altruism.

The atrocities of the Double Tenth incident were the focus of a special trial conducted on March 18, 1946 against 21 kempeitai members of the Singapore Branch. At this trial, one of the accused, Warrant Officer Monai Tadamori (who was eventually sentenced to death) remarked in his affidavit: “I … sent away Mrs Choy. She went back with no sign of pain, just in the same spirited condition as she came in.”

She was released after 193 days, stepping out of the YMCA building in the same clothes that she entered it in. (These clothes are now on display in the National Museum of Singapore.) Her husband was sentenced to a further 12 years in Outram Prison. She was not to see him again until the war ended.

“I shall not forget but I shall forgive”

When the Japanese surrendered in 1945, Elizabeth Choy was invited by Lady Mountbatten to witness the official surrender ceremony on the steps of the Municipal Offices (now City Hall).

She refused to name people for execution. “I don’t blame the soldiers,” she said. “It was the war that was wicked.”

She was escorted by the Governor of Singapore, Sir Shenton Thomas, and his wife, to whom Elizabeth had sent medicines while she was interned in Changi. That act of kindness had not been forgotten.

She was given the opportunity by the returning British to seek retribution against her torturers.

She refused, however, to name a single person for execution. “It’s all over, finished,” she said instead. “I don’t blame the soldiers. It was the war that was wicked and evil … I shall not forget but I shall forgive.”

Elizabeth Choy was proffered the OBE (Order of the British Empire) and invited to England. While her husband returned to his job and did not accompany her, Elizabeth made the journey to England and the self-described “wild woman of Borneo” met the Queen as well as a young Princess Elizabeth.

In addition to the OBE, Elizabeth was also awarded the Bronze Cross, the Girl Guides’ highest honour, by Lady Baden-Powell. The Rajah of Sarawak also presented her with the Order of Sarawak.

Elizabeth with her students in St Andrew’s School. Photo from Ministry of Information, Communication and the Arts, Courtesy of the National Archives of Singapore.

On her return to Singapore from Britain, Elizabeth resumed teaching and became involved in the political developments preceding independence.

When I was taken by the kempeitai, and there was no one who could help me, my only source of strength and comfort was God.

From 1951 to 1955, she was nominated by the Governor to the Legislative Council of Singapore, where she spoke on behalf of the poor and needy and campaigned for the development of social services and family planning.

Her wartime experiences had inculcated in her the belief that civil development required effective protection from aggressors. She served as a second lieutenant in the women’s auxiliary of the Singapore Volunteer Corps, where she earned the nickname “Gunner Choy”. She became a role model for women in volunteer work.

In 1953, she represented Singapore at the Queen’s Coronation and subsequently undertook, for the Foreign Office, a lecture tour of North America to explain the aspirations of the people of Singapore and Malaya.

Looking for blind children in kampungs

Her teaching career at St Andrew’s continued till 1974. Elizabeth established a special bond with her students, and this was exemplified in a testimonial that Canon RKS Adams wrote for her in 1956 when she sought leave to head the work at the School for the Blind.

He wrote: “Not only has her teaching been skilled, but from the first, even before she received her training in teaching, she showed a love and leadership among small children that gave so much more than material knowledge.

“Her warm sympathy with them enabled her from the outset to build up in them values that I have seen come to fruition in her pupils as they grew up.”

After her retirement, she continued with her social work and school visits well into her nineties.

Elizabeth Choy in 1989, wearing her medals. She had been invited to dine on board the royal yacht, the Brittania, with Prince Philip and Queen Elizabeth II who were in Singapore on a state visit. She was advised to wear all the medals that had been awarded to her. Photo used with the kind permission of the family.

In between, she managed a four-year spell from 1956 to 1960 as the first principal of the School for the Blind. This was pioneering work and she described her work in her 1973 interview, saying: “I used to go to the kampungs to find the blind children and try to persuade their parents or grandparents or guardians to let their children come into the school as boarders or attend the school to learn how to read and write. Of course, to them, the whole thing sounded absurd.

“How can they study when they have no sight? I remember how happy the blind children were. They took any challenge bravely and with determination.”

“He never failed me”

In an interview given in 1973, Elizabeth revealed the source of her strength. She said: “All through my trials in life, I have derived great strength and comfort from my knowledge of God. When I was taken by the kempeitai, and there was no one who could help me, my only source of strength and comfort was God.

“And He never failed me. So I wonder where those who do not believe in God get comfort and strength from when they are in despair or distress. Such words as ‘cast your cares upon Me’ or ‘the peace of God which passeth all understanding’ or ‘you shall have life eternal’ never fail to give strength, courage and hope to all believers.”

Elizabeth Choy Su Moi passed away peacefully on 14 September 2006, at the age of 95.

This story is an excerpt from the book, Diffusing the Light: The Story of St Andrew’s Cathedral, Singapore, A Chronicle of 150 Years of God’s Grace and Faithfulness by Armour Publishing Pte Ltd. It is reprinted with permission.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light