Siblings can be your “allies for life”, once you get past the rivalry: Salt&Light Family Night

by Christine Leow // April 29, 2021, 4:28 pm

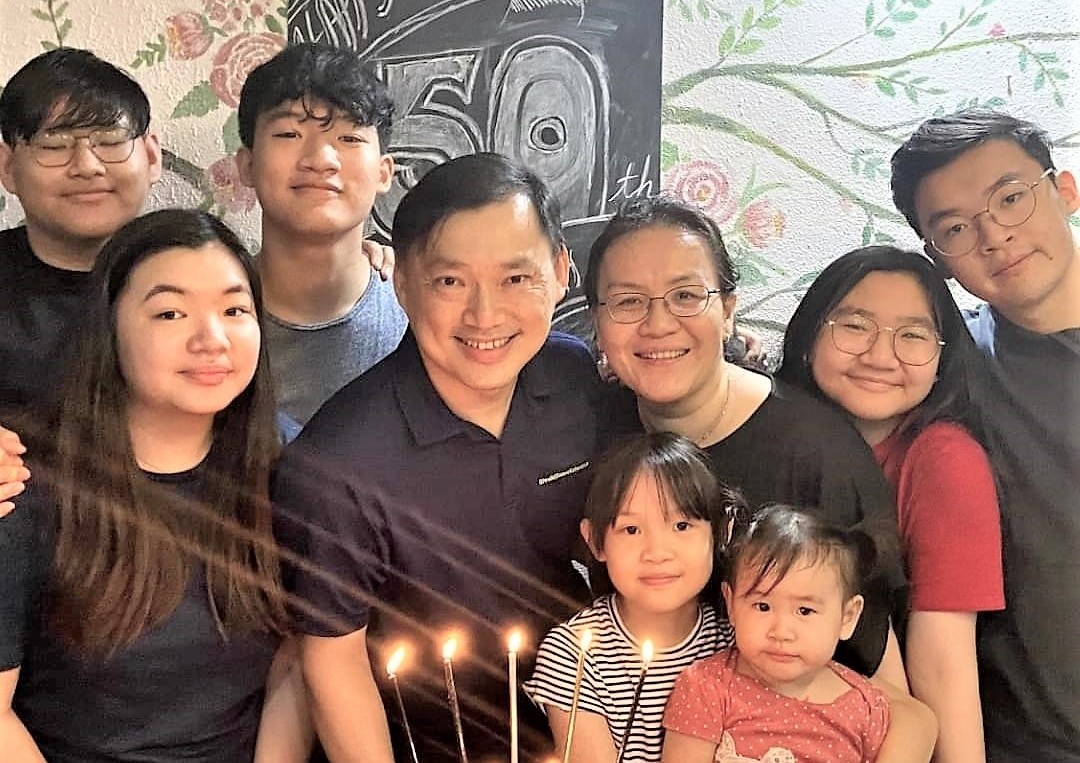

Dan, a vice principal, and Suwei, a homeschooling mum (centre) with their seven children. Though the family is large, they maintain there is no sibling rivalry. Photo courtesy of the Ong family.

It was a glimpse into what the future could hold for parents with young children when 21-year-old Asher Ong declared: “My best friends are my mum and my siblings.”

His words carry plenty of weight considering the fact that he comes from a family with seven children, the youngest 20 months old.

Just how does a family of seven children living in close quarters not dissolve into a morass of competition and contention?

Asher, who just graduated from polytechnic, and his home-schooling mother, Ong Suwei, were part of the panel of three families who gathered on this week’s Salt&Light Family Night (April 27) to talk about their experiences in managing sibling rivalry and building familial bonds.

“My best friends are my mum and my siblings.”

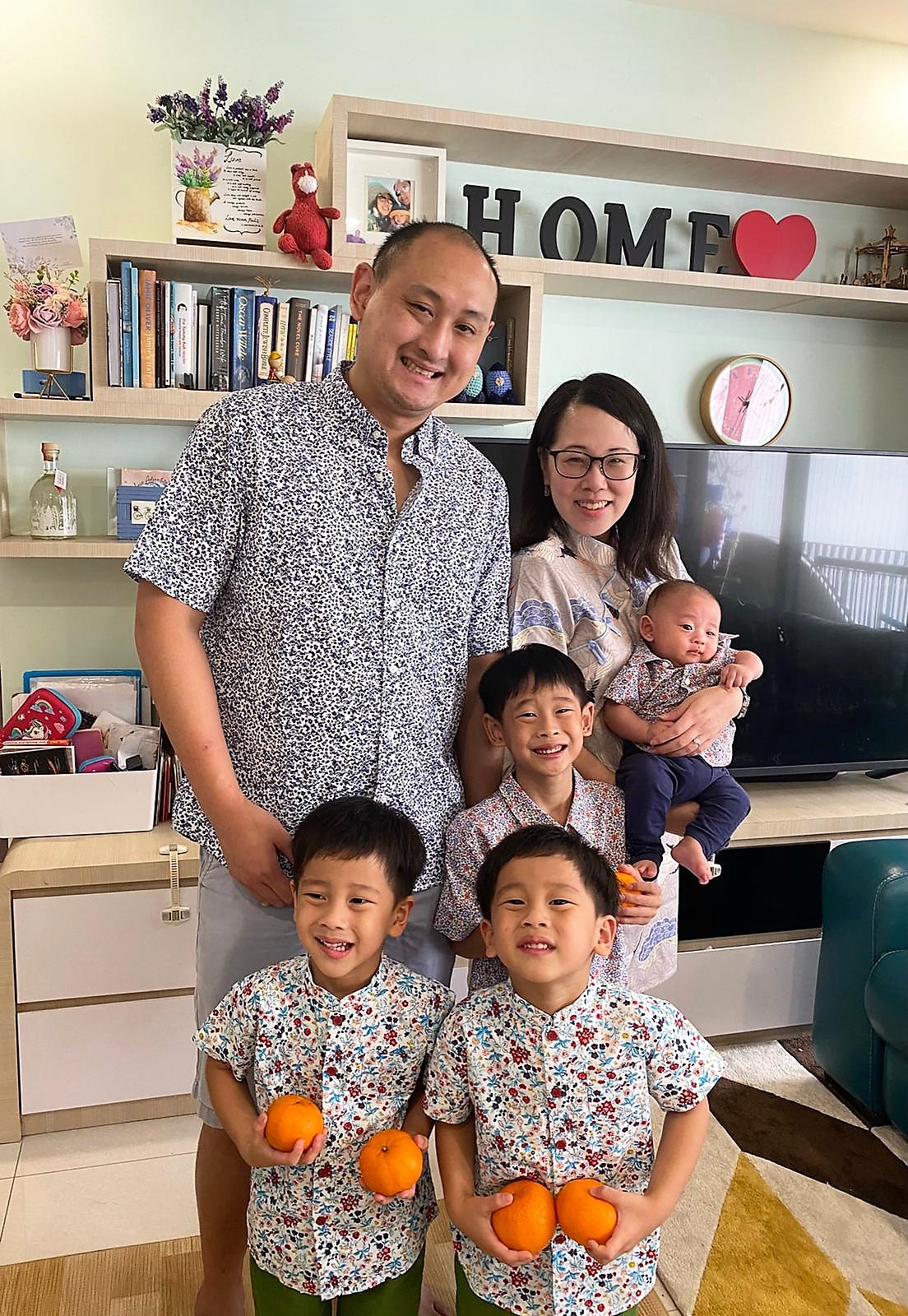

Along with the mother-and-son pair who shared inter-generational insights, were the Lims – Dickson, a senior philanthropy advisor, and Allison, a primary school principal – who had adopted four children, three of whom with special needs; and the Ongs – Yi Kwee, an investment advisor, and Felicia, a young adult pastor – who have four sons aged eight and under.

Most of the Salt&Light viewers who joined the Zoom session were parents (77%) with at least 50% having two children. Another 27% had three children. Primary schoolers and teens made up the majority of the children, while a third were under five.

Here are some of the issues raised by viewers during the Zoom session and wisdom shared by the panel.

What causes sibling rivalry?

The Lims, whose four adopted children are all in primary school, put the cause of sibling rivalry down to both nature and nurture.

Like many siblings, the Lim children are different in personality and they tend to interact better with the sibling with whom they share more in common.

Casting children in set roles can contribute to sibling rivalry too.

Said Dickson: “Different ones will have different types of chemistry. We have two foodies out of the four. They relate very well over food and they also share well. When you bring the other two, it sometimes disrupts the chemistry.

“The other two non-foodies are more introverted. Therefore, they prefer not to be disrupted. When the other two very sociable creatures come into their space, they tense up. That is the nature part.”

The Lims believe raising the children to learn to get along with differences as they “live as a family” is important. That is the nurture component that can stave off sibling rivalry.

Dickson and Allison Lim with their four children. They balance communal living with individual space to manage sibling rivalry. Photo courtesy of the Lim family.

Another aspect of nurture is relating to the children according to their different love languages and teaching them to do likewise. Allison said that this helps the children to “take a step back” and see beyond themselves to be empathetic of others.

Something else that can unwittingly contribute to sibling rivalry is casting children in set roles.

“I always subconsciously aimed to be more like my sister and I always felt I was not as good.”

Said Felicia: “For example, we may say, ‘This is the smart kid. This is the kid that can build Legos without looking at instructions. This is the funny guy’. Sometimes we cast them in these roles and keep repeating it.

“Or we say, ‘This is the good kid’, which makes the poor kid really stressed, thinking he always has to be the good kid. Sometimes, this is done unintentionally but it can cause certain tension and friction between the siblings.”

Comparisons can cause sibling rivalry, too. Suwei grew up with a sister who was a straight ‘A’ student and has experienced the hurt that being compared to a sibling can cause.

“I’m just not so academic. But I always subconsciously aimed to be more like my sister and I always felt I was not as good.”

How do you manage sibling rivalry?

#1 Celebrate differences

The panellists agree that recognising and celebrating differences among siblings can prevent comparisons, jealousy and favouritism that lead to sibling rivalry.

Having grown up with the burden of emulating her sister, Suwei and her husband, Dan, chose to home-school their children so they can tailor the curriculum to optimise each of their children’s talents.

“We can’t just squeeze our children into the narrow expectations of English, Math, Science and Second Language,” said Suwei.

“To us, taking nice photos is important. Someone folding nice origami is important. Cooking a nice meal is as important as doing well in spelling or tingxie (Chinese spelling).

“God has made our children so diverse and so talented in so many ways. As home-schoolers, we can value any kind of wonderful talent and maybe it has lessened the stress of competing.”

“We want to pull away from rivalry and what are we pulling towards is collaboration.”

Asher is all praise for his parents who were always “helping us to discover our individual gifts and nurturing that”.

“There is nothing to rival each other for. We nurture individual talents within this home. Each of us is so different.

“When parents continue to hone their children’s gifts and give them certain experiences to develop those skills, the child then has something to be proud of. And when they are proud of something, each child also learns to respect the others for what they have.

“We create a system that doesn’t allow for such competition to occur and that encourages a more collaborative environment. We want to pull away from rivalry and what are we pulling towards is collaboration.”

For Yi Kwee and Felicia, recognising differences comes down to knowing their children’s different personalities.

Their oldest son, who is eight, likes to “play by the book” while their five-year-old twin sons prefer freer play.

Ong Yi Kwee and Felicia with their four sons, the middle two of whom are 5-year-old twins. Photo courtesy of the Ong family.

“So, he might snatch the toys from his younger brothers because he says, ‘You guys must play the toys this way, let me show you.’ The younger brothers get very upset and it might lead to a fight,” said Yi Kwee.

To allow them to see how differences in playing can be beneficial, the Ongs get the boys to play with them, too, so that they can demonstrate the different ways play can take place. They also try to accommodate each child’s differences to give room for individual expression.

“We tell them, ‘Since kor kor (older brother) likes to play this way, there are a lot of other toys. Let me show you what you can do with these other toys instead,” said Yi Kwee.

#2 Redefine fairness

Part of acknowledging differences is teaching that “fair” does not mean “same”.

Said Dickson: “When we buy something, it doesn’t mean we have to buy four of the same things. The other child may not even like those things, and we respect that.

“But if they like the same thing, they have no choice but to learn to share. We tell them that, by sharing, they get to enjoy two toys instead of one.”

#3 Enforce sharing

In fact, the Lims are big on teaching the concept of sharing because they believe it fosters togetherness.

Said Allison: “We teach that you share to bless, not because you have no choice. And you don’t share your leftovers.”

So, although they can afford to give the children separate rooms, the Lims have made them share rooms instead.

“Last resort is, if you don’t want to share, then it’s mummy’s toy.”

“Our Number One is very introverted. All the more we teach her to engage with others and to get out of her comfort zone. Or it will be more difficult when she has to interact with others.”

To encourage sharing, the family celebrates each time they see a child share so the others can “see the joy of sharing”.

Felicia suggested another way to encourage sharing. She allocates set times for shared toys.

“In our house, the magic word is not ‘please’ because if they say ‘please’, they think they are entitled (to the toy). Consent is the magic word. You have to wait for the answer. If your brother is not done with the shared toy, you wait. The waiting time is 10 minutes.”

When all else fails and the children refuse to share, more drastic measures come into play.

“Our last resort is: If you don’t want to share, then it’s mummy’s toy. And then no one gets to play with it!”

#4 Strengthen ties through shared history

Sharing aside, getting siblings to create shared history can help build ties that last a lifetime, say the panellists.

Six years ago, the Ong family went on a six-month road trip in the United States with their then six children in tow. Baby Megan had not been added to the fold then. They covered 43 states in that time.

Said Suwei: “It was epic. We really, really bonded. That trip was a big marker in our lives as a family. The trip is over but the essence of our togetherness as a family has remained.

“The foundations of the relationship are very important. The foundations are built in childhood and it will come out in the teen years.”

“To us, that is bonding. To them, it is party.”

As the oldest brother, Asher has imbibed the need to strengthen ties with his siblings.

“At this point in my life, between school and NS, I’m really treasuring the time. It’s a very precious time. I take this time to really bond with each of them.”

With some siblings, he enjoys long walks. With one sister, he chats about school and the future. With another brother, their shared interest in Science gives them plenty to talk about.

“We all have different types of relationships. I’m learning how to create more intimacy with my siblings.

“We have a shared history that no one else can relate to, not even our future spouses. The greatest gift that parents can give you is your siblings. You have allies for life.”

For the Lim family, one activity that has helped the siblings bond, which has also created many happy memories, has been their family concerts.

Said Dickson: “It evolved over time. In pre-school, they learnt to dance and perform in class. So, on Friday nights or long weekends, just before bedtime, we say, ‘Show us your performance’.

“Because one danced, another one wanted to show off their singing. And it became like a talent night.”

“What we are trying to do is to exercise gratitude and affirmation.”

The children enjoy it so much that they have dubbed it “party”.

“Now they are much older, it is up to them to create what ‘party night’ means. It becomes a time when they learn to appreciate each other. They act, they create drama or all four sing their own songs.

“To us, that is bonding. To them, it is ‘party’. That becomes orchestrated space. Unstructured to them but to us there is a form of structure that allows them common space to bond.”

Yi Kwee and Felicia also encourage their boys to play with each other to strengthen brotherly ties.

“The three of them share a room. They play with each other and that has created a lot of shared bonding experiences,” said Felicia.

Another family practice is what they call the standing ovation. Each week, they have an informal ceremony where they stand and clap for each member of the family for something kind he or she has done. Even the parents are included.

“So, they know we notice their kindness towards others and that creates pretty good vibes before they go to bed. What we are trying to do is to exercise gratitude and affirmation.”

Why am I refereeing my children’s squabbles? 7 tips on managing sibling rivalry

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light