How “just” is your Facebook or IG post: Melissa Kwee challenges Justice Conference Asia delegates

by Jane Lee // October 18, 2019, 10:27 pm

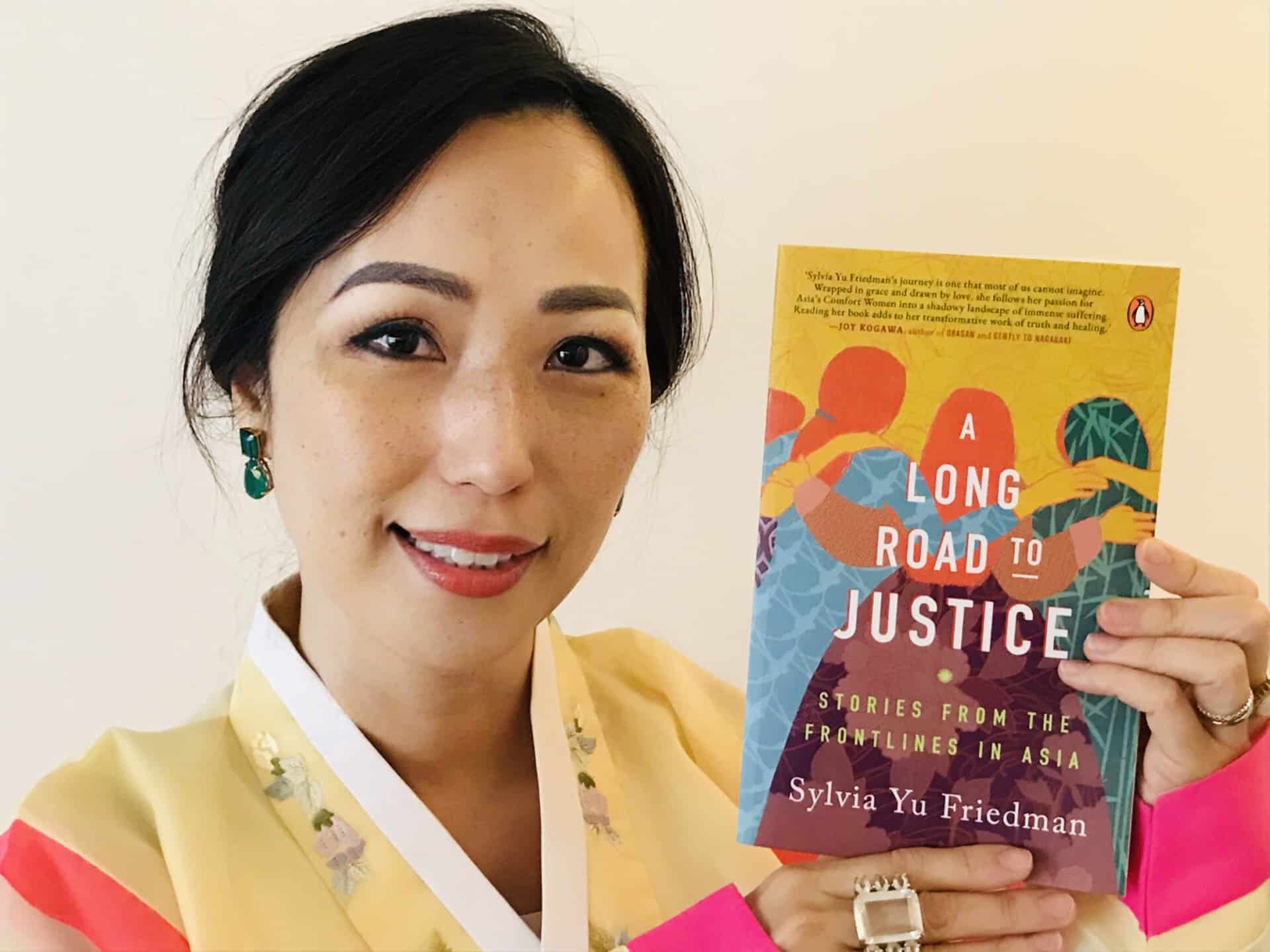

We could all be kinder on social media, said Melissa Kwee, CEO of the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre. All photos courtesy of The Justice Conference Asia.

When we post on Facebook or Instagram, do we pause to consider how our posts or Stories can affect others?

“In fact, we can make life a lot better or a lot worse for people,” said Melissa Kwee, CEO of the National Volunteer and Philanthropy Centre (NVPC), at The Justice Conference Asia 2019 today.

Citing research on the psychological distress that social media can trigger, she added we could all be kinder online, for example, by living out the eight Beatitudes, which the Diocese of Oxford, Church of England, recently re-imagined for social media.

For example, where the Bible says, “Blessed are those who mourn…” (Matthew 5:4), the diocese’s practical approach is: “I will tread softly and post with gentleness and compassion.”

“Justice is more than equality or fairness. It is the pursuit of the right and good”

“These are things we can actually do in our own lives every single day,” said Kwee. “At the end of it, we can bring our tithes and offerings, but if we don’t practise justice, mercy and faithfulness in our daily lives, what does that ultimately mean?

“Justice is more than equality or fairness. It is the pursuit of the right and good – which is a relational condition. It is bringing heaven to earth – the kingdom of God into our lives here and now.”

One of the largest biblical and social justice conferences from the US, this is the first time that The Justice Conference is being organised in Singapore.

Held today and tomorrow at Pentecost Methodist Church, the conference features both local and international speakers at keynote sessions and workshops on topics such as business for good, communities at risk, trafficking and migration, justice and the Gospel, as well as creation care.

Do you know your neighbour?

The idea of “other-centredness” was the running theme throughout todays’ sessions and workshops, true to the event’s aim to open up a conversation on the call “we carry to reach out toward the ‘other’ in compassion, justice and love”.

Yet who exactly is this “other”, or this “neighbour”?

“You can theologically somehow construe it but you really can’t love your neighbour if you don’t know your neighbour,” said Eugene Cho, founder and executive director of One Day’s Wages, which aims to alleviate extreme global poverty.

It’s easy to love neighbours that are like you but Jesus means for us to especially love those that are not like you, said Eugene Cho, founder and executive director of One Day’s Wages.

Referring to a research conducted in the US to study racial relationships, he said that when white people were asked to detail their relational network, out of 100 friends, 91 were white.

In Singapore, how many of us have friends who are different from us?

“You can’t really love your neighbour if you don’t know your neighbour.”

The irony is that while we are trying to have substantive conversations on transforming the society, we actually don’t know one another, Cho posited.

“It’s easy to love neighbours that are like you, that look like you, that feel like you, that worship like you, that dress like you, that go to the same church as you,” he said.

“But all of Jesus’ stories about loving your neighbour conveys to us that to love your neighbour also means to love especially those that don’t look like you, think like you, feel like you, and even those who won’t worship like you – I don’t know about here in Singapore but, in the United States, even those that don’t vote like you!” he continued, as laughter broke out in the auditorium.

“Whether we articulate it or not, there is a sinful thought festering in our minds and hearts, that says ‘I’m better’.”

My neighbour, my teacher

The founder and former senior pastor of Quest Church in Seattle went on to explain that relationship comes into play when loving one’s neighbour.

“It’s not just ‘Oh I have dignity for you’, then we walk away. When we see a person, that person reflects God’s image and therefore there is a desire to engage in a mutual reciprocal relationship – I have much to learn about God’s image in you.”

About 350 delegates attended the two-day conference at Pentecost Methodist Church in Pasir Ris.

When Kwee trains volunteers, she tells them something similar too.

There are three types of volunteers, she would say. The first type is the “I-It” relationship. “It’s a problem so I should help. It is a statistic which is growing, and it’s not good. It is a reason for me to feel good about myself,” she explained.

The second type is “I See You”. These volunteers understand that people are dealt different hands in life and some have more while others have less. It’s an “objective” relationship.

Then she would ask them to imagine a third possibility that was preferable: “This is the volunteer that holds the other with honour and respect as your teacher, as the one who will really bless you, that will shape who you are, and for whom and to whom you can be forever deeply grateful.”

“I have much to learn about God’s image in you.”

Kwee, the key mover behind NVPC’s new strategic vision of building a City of Good that was launched on Monday by President Halimah Yacob, is hoping that Singaporeans will think beyond themselves.

“It is the spirit of self-centredness that keeps us focused on ourselves, that preoccupies our mind. It keeps us from experiencing gratitude, and expressing that gratitude for what we have and where we are,” she noted.

The opposite is other-centredness, to be a steward of what we have, practising gratitude and being empathetic, she added.

Encouraging the delegates to be faithful with what they have, Kwee ended with a plea: “It is ultimately this other-centred spirit that, I pray, as the people of God, the people of good, we will lift up to bring to our City of Good.”

How “just” is your Facebook or IG post: Melissa Kwee challenges Justice Conference Asia delegates

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light