The story behind the world’s most commonly used Chinese Bible

The Bible Society of Singapore // August 14, 2019, 4:34 pm

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Chinese Union Version Bible. Photo by chris liu on Unsplash

In 2019, the Chinese-speaking churches across the world celebrate the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Chinese Union Version (CUV) Bible, known as heheben (和合本) in Chinese, which means “drawn together in a whole book”. Today, it is the most predominant translation used by most Chinese Christians and Chinese-speaking churches across the globe.

Bible translation work had begun in China since as early as 7th Century AD.

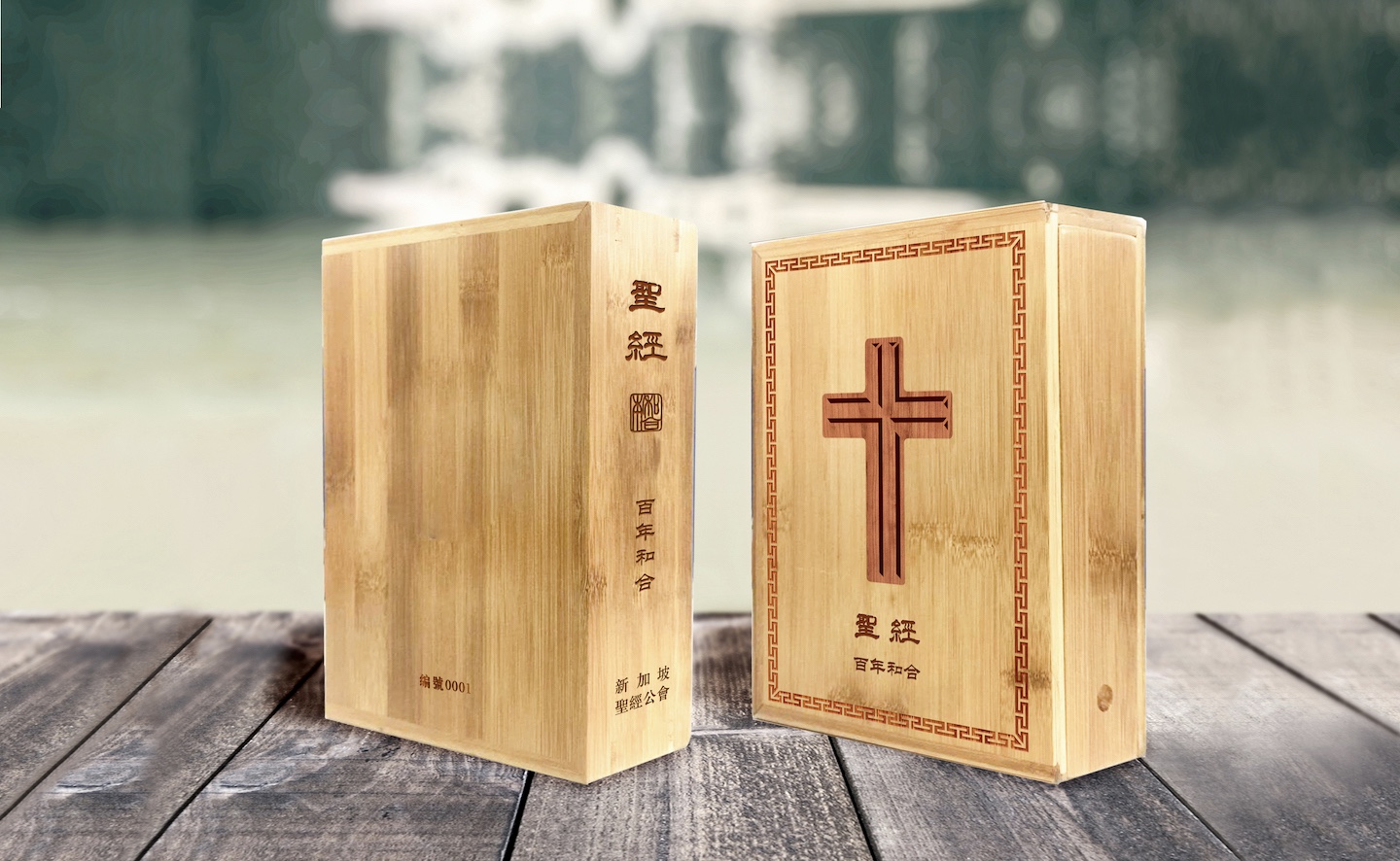

In celebration of this significant milestone, The Bible Society of Singapore has produced a Special Edition CUV Bible – a replica of the original CUV Bible texts that were first published in 1919. This Bible is a limited global edition, with only 1,000 copies available.

The Bible comes in a wooden box, with a three-dimensional engraving of a cross on the front, and a serial number inscribed on the back.

The cover of the Bible is made from bamboo, a material that is highly valued in Chinese culture because of its versatility. Ancient Chinese scholars also interpreted bamboo as a symbol for gentleness, one of the beatitudes from the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5:5).

Origins of the CUV Bible

Even though Bible translation work had begun in China since as early as 7th Century AD, the first Chinese Protestant Bible only appeared in 1822 – translated by Joshua Marshmann, in easy Wenli (文理), a language which was closer to the way people spoke.

A year later, Robert Morrison and William Milne produced a translation of the Bible in high Wenli, a language only understood by scholars. The 1823 Morrison-Milne Bible, in spite of its use of complex language, eventually became the foundation for Chinese Bible translation. There were also versions of the Bible translated into the Mandarin dialect, such as the Peking Version, published in 1872.

By the second half of the 19th Century, there was a plethora of Chinese Bible translations – in easy Wenli, high Wenli, and vernacular Chinese, baihuawen (白话文) – done by missionaries hailing from different countries, denominations and mission societies.

The Mandarin Bible was a 29-year-long translation project, the largest in the history of the Chinese Protestant Church.

Eventually, the need for a unified version of the Bible that was accepted across all Protestant denominations grew, for more effective evangelising and nurturing of Chinese Christians.

In 1890, at the General Conference of Protestant Missionaries held in Shanghai, a formal proposal was approved to translate a “Union Version” of the Chinese Bible into three languages – high Wenli, easy Wenli and Mandarin, to reach out to different audiences.

The union version in easy Wenli was published in 1902, while the high Wenli version was published in 1907. The Mandarin version took a much longer time to be translated – the New Testament required 13 years to complete, and the Old Testament another 16 years – making it a 29-year-long translation project, the largest in the history of the Chinese Protestant Church.

The translation of the CUV Bible into Mandarin was a complex endeavour for a few reasons.

Firstly, Mandarin had yet to be a clearly defined language at the beginning of the 20th Century. Hence, the missionaries had to enlist the help of various Chinese scholars to help with the translation, such as Zou Liwen, Wang Yuande and Cheng Jingyi.

Secondly, Mandarin was not as highly regarded as Wenli; the latter was known as the language of the Chinese classics, while the former was regarded as a language that did not have much cultural significance. In spite of initial difficulties, the Mandarin CUV Bible was eventually published on April 22, 1919, with the collective effort of various Chinese scholars, missionaries and Bible Societies.

Increasing popularity of the CUV Bible

Although scholars and missionaries initially underestimated the value of the Mandarin CUV Bible, the events in China’s history would eventually propel it into the spotlight.

From the mid-1910s to 1920s, efforts to transform China from a traditional dynasty into a modern nation-state meant that there was a need to replace classical Chinese and the various dialects with a single, unified spoken and written language. The breakthrough came in the form of the May Fourth New Culture Movement, just days after the publication of the CUV Bible.

In celebration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Chinese Union Version (CUV) Bible, The Bible Society of Singapore has produced a Special Edition CUV Bible – a replica of the original CUV Bible texts that were first published in 1919. Photo courtesy of The Bible Society of Singapore

Following this, the CUV Bible quickly became recognised as one of the few texts that used a vernacular, Mandarin-based unified national language, thus gaining the endorsement of many. One of the unique features of the CUV Bible was that it was largely based on vernacular Chinese, while also incorporating some elements of classical Chinese – which made it appealing to both mainstream and educated audiences.

The CUV Bible hence became a model for vernacular Chinese; it was also used as a literary reference for some Chinese writers.

Impact of the CUV Bible

Apart from its role in helping to spread and standardise Mandarin as the national language of China in the 20th Century, the CUV Bible also helped to shape the growth of the Chinese Church.

The years after the publication and distribution of the CUV Bible marked the formative years of growth for the Church in China. Chinese Christians began to assume leadership positions in churches; some of them even began to initiate evangelical revivals across the country.

The availability of the Bible also contributed to increasing literacy rates in China.

Furthermore, the translation process of the Bible had produced a rich treasury of theological terms in the Chinese language, which helped to shape Chinese Protestant theological understanding and tradition.

The availability of the Bible also contributed to increasing literacy rates in China. In the 19th Century, 99% of women and 90% of men in northern China were illiterate. With the CUV Bible now available in Mandarin, it proved to be a useful medium for the masses to learn to read and write in the vernacular.

Protestant missionaries used the Bible to teach the Chinese, while simultaneously preaching the Good News. Baptism regulations also became an added impetus for Chinese Christians to acquire literacy skills, as it required believers to memorise the Ten Commandments and the Lord’s Prayer.

To meet this need, some churches and evangelistic meeting points began running literacy classes for their members.

Protestant missionaries used the Bible to teach the Chinese, while simultaneously preaching the Good News. Photo by Chris Liu on Unsplash.

Today, Chinese academia still acknowledges the CUV Bible’s influential role in modern Chinese literature.

The CUV Bible is also the most cited Bible translation used by scholars when quoting biblical terms in secular writing, and is still well-loved by Chinese-speaking churches and congregations across the world.

Bibles in 21st Century China

Since the implementation of the Open Door Policy in 1978, the demand for Bibles in China has increased exponentially. To meet this need, Amity Printing Press was established in 1987, printing affordable Bibles for those that hungered for Scripture.

Majority of the Bibles are distributed to Christians who live in rural areas and are unable to afford Bibles of their own.

Since its establishment over 30 years ago, Amity Printing Press has printed more than 180 million copies of the Bible for Christians in China and beyond.

Today, it has an annual printing capacity of nearly 20 million Bibles, producing an average of one Bible per second. A large majority of the Bibles produced by Amity are distributed to Chinese Christians who live in rural areas and are unable to afford Bibles of their own.

In the province of Henan alone, there are 3.8 million Christians living in remote areas, surviving on less than US$150 a year. The standard Bible costs about US$2, equivalent to the cost of 20 eggs.

Li Yue Ying carrying her two-year-old niece, Li Si Ying, to church – a two-hour walk away from her home. Photo courtesy of The Bible Society of Singapore.

In Hunan, Li Yue Ying endures a two-hour long walk to Luo Shui Church every Sunday, while carrying her two-year-old niece, Li Si Ling, on her back. Despite the physical strain, she faithfully goes through this routine because of her love for God and the community that she has in church.

When she found out that a Bible Distribution van would be visiting her church, she was ecstatic. She had been longing for a brand-new Bible, as her old one was worn out.

The Bible Society of Singapore supports Bible distribution efforts in China by mobilising Bible Distribution drives, so that more like Li Yue Ying would be able to receive and be blessed by the enduring Word of Hope.

Donations of $500 and above made to The Bible Society of Singapore will receive the special-edition CUV Bible. Donors may also customise the serial number at a separate cost. Please contact [email protected] for more information. All proceeds will go towards the furthering of the Bible Mission and Bible distribution efforts in China.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light