I meet Bryan Tan at his home on a drizzly January evening, and I wonder if I’ve stepped into a Toys ‘R’ Us showroom.

Neon balls nestle in plastic goalposts in the corner of a small garden, while a rubber toy bobs about in a bright blue, inflatable pool. We are meeting at his house, a quiet, rented apartment in central Singapore, because “it’s important for me to at least be at home during dinner,” he says.

We chat at his picnic table as the sky turns dark, accompanied by the sounds of piano practice from indoors. Tan’s seven-year-old son, Michael, offers me a glass of cold water.

If first impressions count, this is a home surely befitting the CEO of the Centre for Fathering, a non-profit organisation that aims to get dads more involved in the lives of their children.

Besides overseeing operations, Tan also writes columns on fathering for national newspapers, among other things. Indeed, the soft-spoken 42-year-old appears to have been preparing for fatherhood all his life.

But that couldn’t be further from the truth.

Reluctant dad

“I never wanted to be a father,” he says simply, Michael out of earshot. “When my first child was born in 2010 I didn’t know how to manage that. I was really overwhelmed with managing a marriage and a child.”

Back in 2010, Tan was an army officer climbing up the ranks, en route to what he calls the peak of his career in the military.

“There were times when I wished I didn’t have to deal with the distraction of family,” he says candidly. “I had the misconception that the early years of a child’s life was really to be spent with his mum. I was glad to just kind of leave it to my wife.”

So when his wife, Adriana, found work in Hong Kong, he says he “naturally encouraged her to go”. Adriana took his son along, and they lived overseas for the next three years, during which time he became a “commuting dad”.

He enjoyed the independence only for the first two days. The house started feeling empty soon after.

“My wife really liked the job there, but I think she also left because she knew that I wasn’t around most of the time,” he says. “To her it didn’t make much of a difference.”

For Tan, this reticence towards fatherhood stems from his own experiences growing up.

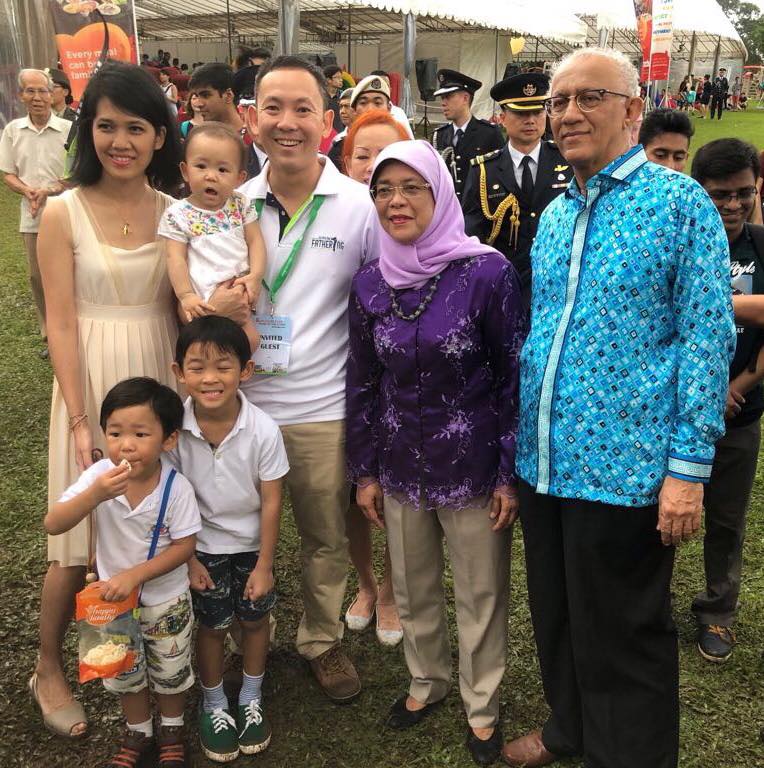

Bryan Tan and his family with President Halimah Yacob at the 2017 Family Weekend Picnic

“I didn’t have a (positive) role model,” he says. “My dad was so busy providing for the family that he wasn’t around in the early years.”

But despite being a self-professed “reluctant dad” himself, something was stirring within him – a desire to “serve the fatherless and give voice to the voiceless”.

“I couldn’t understand it,” he says. “I wasn’t even a dad then. So I left it there and I threw myself deeper into work as a form of distraction.”

In 2014, his second son, Joshua, was born and the family had to move back to Singapore. But instead of a happy reunion, he only found frustration. The couple had grown distant.

Despite the family “being well taken care of”, there was “little emotional investment”. He knew it, and so did his wife. He had avoided the issue for years, until he could do so no longer.

“I started to develop feelings of guilt for not being a good husband, for not being a good father, and naturally not being a good son because I had a strained relationship with my dad,” he says.

“At that point I knew that whatever I did at work didn’t matter if my wife couldn’t love me like she used to, and I did not know my kids.”

That year, he started developing “chronic pains” in his body. And work slowly but surely began to lose its charm.

“Dealing with the family that had moved back, the new child, the pains, and also the lingering feeling that I wasn’t getting much satisfaction out of my career – it got to the point where I didn’t know what to do with my life.”

The Father’s heart

At that point in 2014, he was “a faithful Sunday Christian” growing up with a mixture of religious influences. Faith and church for him was a matter of fulfilling an obligation, nothing more.

“But when I broke down, that was when I first encountered God,” he says. “I just didn’t know what to do. I went down on my knees and wept and submitted my life back to Him. And there was that sense of peace and reassurance that He was there, that He was going to guide.

“I knew I had to make some changes, but I didn’t know how.”

In October 2014, despite being just 38, Tan signed up for Halftime, a one-year coaching programme designed to help mid-career adults rediscover or find their calling in life.

There, his mentor helped him rediscover and finally embrace his purpose: To serve the fatherless and to give voice to those who didn’t have a voice.

The next step for him was to get connected with people who were involved in the local fathering community, or as he puts it, “realising that you’re not alone”. Among others, he would meet Jason Wong, founder of Dads for Life, a national movement that the Centre oversees today. Wong would become one of Tan’s spiritual mentors.

“For the first time, that gave me the first sense of community,” he says. “And because these were godly Christian fathers, I got grounded in what being a good Christian father was. I finally got to understand the Father’s heart.”

One evening over dinner, Wong asked him to join the Centre for Fathering.

“Everything in me protested,” he says. “I wasn’t prepared to leave my job, to give up the security of a public service job to join a non-profit.”

Tan (extreme left) with Patron of Centre for Fathering & Dads for Life, Speaker of Parliament Tan Chuan-Jin (centre), and Centre for Fathering Chairman Richard Hoon (extreme right) at a 938 Now radio interview with deejay Susan Lim

Ten questions

The Centre for Fathering programmes include talks, workshops and camps designed to bring fathers and their children closer together. One such event that Tan attended with his son Michael – “Breakfast with Dad”– eventually led him to take the plunge.

“There were 10 questions I had to answer about my son,” he recalls. “I realised I couldn’t answer a single one. I didn’t know his shoe size, his favourite colour. I didn’t know the name of his teacher or even his best friends in school.”

About 14 fathers took part that day. At one point, the children had to stand around the corner while the dads would call out their names, an exercise to see how well they knew their father’s voice. The first two fathers shouted but the wrong kids came. Everyone started displaying looks of disapproval.

“But when it came to my turn, it wasn’t funny anymore,” Tan says, his voice quivering slightly. “I had to shout three times before my son came – and when he came, he actually asked, ‘Daddy, is that you?’

“I felt like my heart was stabbed and torn in two. I didn’t know my son, my son didn’t know me, and at that point I knew that whatever I did at work didn’t matter if my wife couldn’t love me like she used to, and I did not know my kids.”

Peace amidst the storm

He resigned soon after to join the Centre for Fathering, a process that took about eight months. “Every day was a struggle,” he says. “Every day I wanted to retract that decision. And there was the fear of the unknown, the anxiety of a change in lifestyle for the family as well.”

Jason Wong and other spiritual mentors helped guide him along the way, but Tan says it was God that finally brought him peace … something he would sorely need in the coming days.

His wife was retrenched the week he tendered his resignation. And at the end of the same week, the couple discovered that they were going to have a third child – “so all signs pointed to me retracting (the resignation), and staying put”.

“I mean I struggled with all this,” he says, unclasping his hands. “As a couple we struggled. But we found the peace to go ahead and we continued to stay the course.

“I found my confirmation directly through Him. It’s through my relationship with Him, my time with Him that I could really find the peace to take that leap of faith.

“And it’s also through my wife. I don’t do anything that she’s not congruent with.”

On August 1, 2016, the day before he would start work at the Centre, Tan discovered that his parents were undergoing a divorce.

“I felt most unworthy to be helming this organisation,” he tells me. “When I entered the Centre for Fathering, I entered the Centre as a broken person.”

But to paraphrase Paul’s words in 1 Corinthians 1, God hardly calls the qualified.

“It was quite apt that I entered Centre for Fathering to be restored as a father, as a husband and as a son,” he says. “Even though my parents were filing for divorce and I felt so broken, I found my identity in Christ. I was a child of God. I had been given a second lease on life to make things different.

“When we take that first step of obedience, the rest of the way is revealed. God has already been at work in all these communities and spaces, and all I had to do was to see where He was and just to partner Him.”

Reconciliation

Divorce rates are the highest in years, according to official statistics. More children and fathers are living apart. But more individuals, companies and schools are getting involved with the Centre for Fathering.

Over 600 organisations took part in the Centre’s annual “Eat With Your Family Day” in 2016, twice the number from the year before, Tan says. The Centre has also been approached by groups from 21 countries for advice on starting similar movements.

“What keeps me going is really the excitement, because I get to see what God is doing, get to steer our efforts towards partnering Him to fortify families and to help families seek reconciliation – and this applies across all faiths, all families.”

And for Tan, that reconciliation has also happened close to home. In June 2017, he set out to patch things up with his own father.

“I was led to the revelation that it wasn’t so much about what my dad did to me, but the bitterness that I held,” he confesses. “I started to see my father for who he was – as a child of God.”

Today father and son are in the midst of reconciliation. His chronic pains are completely gone; they disappeared “the moment I made the decision to reconcile”.

And he is not done yet. As our conversation draws to a close, his sons emerge from indoors and rush into his arms. He tells me he does not hide his own past from his kids, including his relationship with his father.

“I want them to see me (reconciling), to see me vulnerable,” he says. “Because I owe it to them. Every time they ask ‘Where’s Grandpa?’ I have to tell the truth: This is where we are, and this is what I’m trying to do.”

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light