“Less of me and more of You”: A nurse’s journey from aesthetic medicine to end-of-life care

This series of interviews commemorates Singapore Nurses' Day on August 1, 2020. Salt&Light salutes all nurses for their dedication and care!

Anna Cheang // July 29, 2020, 4:03 pm

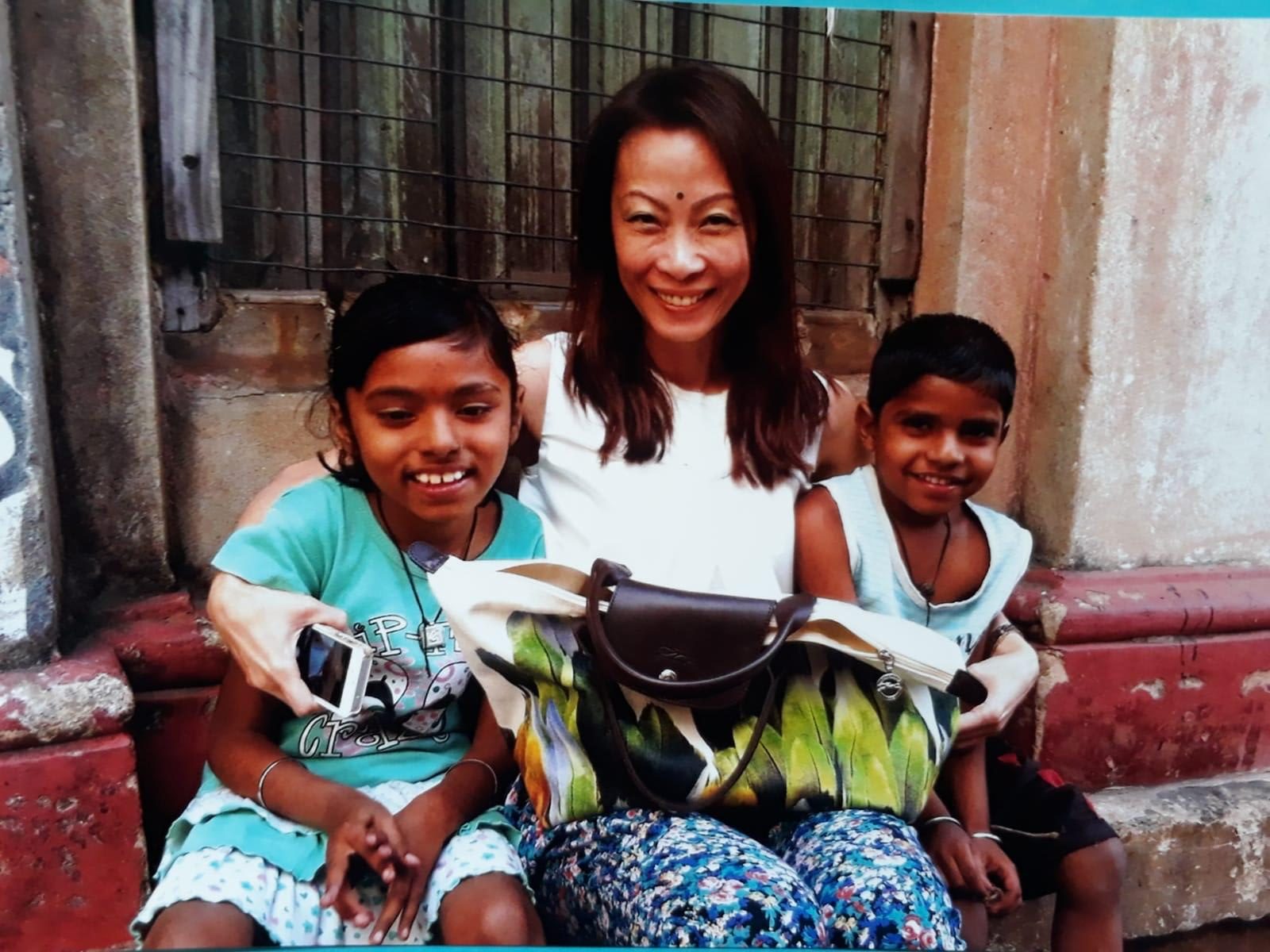

Award-winning palliative care nurse Amy Lim with Augustine Dhirgahayoe, an Indonesian patient she took care of for a year. All photos courtesy of Amy Lim.

The Prada slippers that nurse Amy Lim had taken off on her patient’s doorstep were gone by the end of her visit.

The frantic search of the HDB block was futile. Lim, then 42, had no choice but to leave for her next home visit wearing the best slippers from her patient’s family.

She broke down the moment she entered the taxi: “God, this is the life you’ve called me to?”

It was 2008. Lim was three months into her job with HCA Hospice Care. The association provides free home hospice care to terminally ill patients from all walks of life. The passing of Lim’s father-in-law had inspired her move to palliative care.

“The drab uniform was bad enough. But if I also had to wear the black ugly covered shoes you see at the hospital, I would not have stepped in,” Lim, now 54, told Salt&Light, only half in jest.

Overcoming her initial vanity, Lim has gone on to receive recognition, including the prestigious Nurses’ Merit Award in 2014, for her dedicated service.

Since 2019, she has been in charge of training and supervising new nurses on home visits, and formulating SOPs (standard operating procedures) for HCA as a nurse educator.

Cosmetic love

Lim became a Christian at age 13, but she had made little effort to build on her faith. “God was never so important to me,” she says, admitting that she only turned to God when she needed help.

But she heeded the call of Philippians 2:3 in her choice of career: Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility count others more significant than yourselves.

“I looked at that verse and thought: Hey, that is the call of a nurse.”

Lim started her nursing career in 1986. She was in obstetrics and gynaecology (O&G), before moving to aesthetics in 2003.

But she heeded the call of Philippians 2:3 in her choice of career.

The aesthetics clinic was luxurious and spa-like, always air-conditioned, with a sweet aroma in the air. She assisted doctors with laser treatments, Botox, fillers and the such.

She attended to beautiful air stewardesses, models, celebrities and the Who’s Who of society, and was well-liked by them. It only served to reinforce her pride.

“No matter how famous they were, they had to be nice to me, because I was doing treatments for them.

“I was in a very comfortable place.”

At the time, she attributed her competence and achievements to her own positive attitude towards work and life. Not to God.

SARS wake-up call

But while working at a clinic in 2003, Lim attended to a family member who was subsequently diagnosed with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

“Whether or not I walk out alive from CDC, it was all within the hand of God.”

Lim developed a persistent fever while quarantined at the Communicable Disease Centre (CDC) and was later diagnosed with the respiratory disease. It was just six months after she had given birth to her youngest son. She had to give up breastfeeding prematurely.

The experience made Lim realise that she was not invincible.

“Human beings are so vulnerable. No matter how much you plan, no matter how powerful you are, you can be gone in an instant.

“Whether or not I walk out alive from CDC, it was all within the hand of God. There is no one and nothing more powerful than God,” she says.

The dilemma

Lim’s father-in-law contracted pancreatic cancer in 2006.

A first scan showed that the tumour had not spread.

But Lim could tell that something was off after her father-in-law went for surgery. He remained fatigued and had no energy – a stark contrast to his usual active self.

Lim regretted that she lacked the knowledge to provide the care that her father-in-law required.

Unsettled, Lim took him back to the hospital. A second scan revealed that the cancer had spread to his lungs and liver.

The family now faced a devastating dilemma: Have him go through chemotherapy for six months and wipe out their savings, or forego the treatment and let him pass away.

Lim felt anger at the false hope the initial scan had given, and utter helplessness at the situation.

She stayed at his bedside throughout his hospital stay, witnessing the way his condition quickly deteriorated, and how he coughed fresh blood for the first time.

Her father-in-law passed away a day after he was discharged from the hospital, three months after being diagnosed with cancer. The home palliative care that had been arranged never had a chance to happen.

Lim regretted that she lacked the knowledge to provide the care that her father-in-law had required.

Just five months earlier, she had witnessed a team of nurses caring for her friend who had colon cancer, helping her prepare for death.

Lim felt the pull towards palliative care. She was also encouraged by Dr Tan Chek Wee, a longtime palliative doctor at HCA Hospice Care. “He told me that it was time for me to come into palliative care.”

And so she took that leap of faith.

The departure hall

Palliative care couldn’t be more different from her job at the aesthetics clinic.

Lim’s work is focused on improving the quality of life for patients who are terminally ill and relieving their physical discomfort. She needs to be familiar with their medical histories and previous treatments.

“These are people who are already at the departure gate. They are no longer just booking their ticket hoping for a good holiday,” she says.

Also crucial is upholding their dignity. She relates to them as individuals to understand their hopes and desires at this stage of their lives.

Besides taking a 50% pay cut, her work now involved treating serious cancer wounds. She faced a wide range of patients. Many appreciated her efforts. Some did not.

Amy in Kolkata, India, where she volunteered with Missionaries of Charity for a week. Her love for humanity has taken her beyond the comfort of home to places like Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

The nature of home care places patients “in a position of great autonomy”.

“When patients are in the comfort of their own homes, we nurses are their guests. We are in their territory,” she said.

Even as she tried her best to journey with her patients and their families, she encountered patients who refused to see her and was often critiqued unreasonably by the patients’ caregivers.

The higher hand

Although she felt like giving up during the first few months, her ego kept her going.

Lim felt embarrassed about quitting so soon. Especially after telling everyone that palliative care was her divine calling. Not even when an aesthetics doctor reached out with a job, dangling a five-figure pay cheque.

“Of course, I left a back route for myself and told him that I would take the job if palliative care didn’t work out,” Lim adds with a laugh.

She decided to give it another three months. The six months then turned into a year.

Looking back, Lim sees the higher hand that had guided her through that difficult first year. God was always in control.

“When I go out to serve patients, I’m not doing it as Amy Lim, but in the image of the Lord.”

This became all the more evident when wearing the black covered shoes became mandatory in her second year of work.

But this time, she realised that the value of her work had far surpassed these superficial concerns.

For Lim, this was a clear, if not shocking, message from the Lord.

The self-image she had always held so dearly – to the extent of only wearing her nurse’s uniform after her favourite tailor had worked some form-fitting magic on it – was really not that important after all.

“I realised that when I go out to serve patients, I’m not doing it as Amy Lim, but in the image of the Lord.”

Pain and joy

Even though it’s been 12 years since she stepped into palliative care, the pain of watching her patients suffer, and losing them to death, remains real.

“From the start, I had a motto to keep me going: ‘Your pain will now be my pain, but your joy will also be my joy.’”

Amy continues to serve her patients with a sensitive heart, sympathising with her patients’ losses and embracing their daily joys together with them.

Even as she bears the heavy emotional toll, she takes comfort in releasing these emotions to God, learning to trust in His sovereignty along the way.

“God wants us to face Him without hypocrisy, to question Him with all our anger and suffering.”

Lim’s love for her patients translates into the way she works to fulfil their final wishes.

“God wants us to face Him without hypocrisy.”

Lim roped in a team of volunteers to help a patient who had terminal lung cancer to publish a 36-page photo diary before he passed on in 2013.

It chronicled his lifelong struggle with drug addiction. The patient had hoped it would encourage young people to stay away from drugs.

In 2017, she saw how her Indonesian patient, Augustine Dhirgahayoe, visited other Indonesian patients who were going through chemotherapy to give them encouragement despite her own suffering from a cancerous tumour on her back.

Before Dhirgahayoe passed on, Lim worked together with a Bahasa-speaking social worker to record Dhirgahayoe’s life story in a book: When Fear Knocks, Let Faith Answer.

Dhirgahayoe’s husband now travels the world and preaches Christ with the aid of the book.

Even Lim’s experience in aesthetics served her patients well. A breast cancer patient had one last wish: For her 10-year-old daughter to hug her.

The patient was bloated, she did not smell good, and she had a lot of facial hair. This made it difficult for her young daughter to approach her.

Lim lovingly waxed her patient’s facial hair and groomed her eyebrows. She got soiled while helping to relieve the patient’s constipation.

But the transformation made it easier for the daughter to embrace her mother in the last two months of her life.

Lim’s journey in palliative care has been many things, including a huge lesson in humility.

“I can now tell God that it is less of me and more of you.”

This is the first story in a series of interviews to commemorate Singapore Nurses’ Day on August 1, 2020. You can find the other stories in the series below.

On the frontlines and far from home: Two foreign nurses draw comfort from giving comfort

Palliative care nurses: Bedside angels to the dying and their families

“It was a miracle”: Dr Cynthia Goh on the chain of goodness that led Bangladeshi worker home

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light