An abandoned building in Tomioka Town, Fukushima. Although the evacuation notice for Tomioka was lifted in April 2017, less than 10% of the population have returned. All photos by Rachel Phua unless stated otherwise.

Rows of silent hostess bars and izakayas line the streets of downtown Iwaki, misty on a cold mid-March morning. The cherry blossom trees are still budding in this city, which lies 50km south of the Fukushima Daiichi reactor.

The city is now the hometown of many evacuees from the surrounding towns affected by the nuclear meltdown of 2011.

“They were not here when I first visited Iwaki in 2011,” mentions my friend, who led this trip to visit several churches and missionaries in Fukushima.

In the car, she rebukes the spirit of mammon as she prays. Money from government compensation, a spike in property prices and the arrival of decontamination workers have caused friction in the once-sleepy fishing port.

It is a metaphor of sorts for the situation in the prefecture – struck not only by an earthquake and tsunami that left more than 22,000 dead or missing across Japan (including disaster-related deaths), but also a major radiation leak that has left its septic trail for years to come.

While most parts of town are back to normal – only 2.7% of the prefecture remains closed – spiritual adversities remain in the aftermath of the tragedy, where mental health issues have gone up after temporary housings closed, and pastors battle against time to reach out to non-Christians.

A lone Paul

In Tomioka, one of the previously restricted zones until April 2017, Pastor Eiji Sumiyoshi, 66, is restoring an abandoned house to launch the town’s only church by fall this year.

He will call it Futaba Hope Church, referring to the district Tomioka is part of. This is on top of his duties as a pastor of Nakoso Christ Church in Iwaki an hour’s drive away where, like many pastors around the country, he plays for worship, preaches, does home visitations, organises outreach events, maintains and lives in the church building, and serves after-service lunches with his wife.

The house that Pastor Sumiyoshi hopes to convert into a church. A church member donated the house, which had belonged to his late parents. The house sits on a hill away from the coast and was only damaged by the earthquake.

But since Tomioka’s reopening, other religions have set up their shrines and sent their priests to support the townspeople, Pastor Sumiyoshi said.

Meanwhile, not everyone at his church in Iwaki is on board with his vision. Many of the members are aged, a few in nursing homes, and have requested for visits, which Pastor Sumiyoshi hasn’t been able to fulfil as frequently as he would like. Some of them have asked why he doesn’t solely focus his efforts on their well-being.

“It’s been hard to keep a balance,” he said. “Every day I’m praying that God will send a helper, like Paul, who didn’t fulfil God’s vision alone.”

Inside the house, which is currently undergoing renovations.

Pastor Sumiyoshi is also worried about the viability of Futaba Hope Church. Only 922 people live in Tomioka, less than 10% of the pre-disaster resident count, and he is not sure how it can be sustained in the long-run once the elderly pass on and the Daiichi decommissioning workers will move away when the project is complete in 30 to 40 years’ time.

A battle against time

Age is another factor the pastors are facing against their ever-burgeoning work for the Lord.

Haramachi Bible Church is located 22km north of the Daiichi plant in Minamisoma. Its pastors, Makoto and Motoe Ishiguro are 72 and 71 years old respectively, but their dream is to set up a share house for its mainly-elderly congregation of about 15.

Soon, many of these members will not be able to travel to church, so living together will make it seamless for them to attend service, and they can live up to the Christian ideal of being a family.

The members of Haramachi Bible Church, taken during their 20th anniversary in 2017. The Ishiguros are on the far right of each row. Photo from Haramachi Bible Church’s website.

Both Pastor Sumiyoshi and the Ishiguros are past the usual Japanese retirement age of 60, and they are unsure how long they can keep the fervour going. The pastors are looking for successors, but it is hard to attract younger folks back – especially due to radiation fears – and there are fewer missionaries to tap on in Fukushima compared to Miyagi and Iwate prefecture.

According to the Japan Evangelical Missionary Association (JEMA), a network of over 1,000 members that connects missionaries in Japan, there are only five missionaries in Fukushima currently, compared to 24 in Iwate and 72 in Miyagi. JEMA’s figures are based on the members registered in its directory, and does not account for all the missionaries in Japan.

Wrestling with loneliness

Simultaneously, the pastors are trying to figure out how to combat the problem of social isolation after a growing number of evacuees moved from their temporary homes to permanent housing.

Though many Christians went out to minister to the survivors who stayed in these temporary housing complexes, the volunteers lost contact with them once the the latter moved to permanent housing across all parts of town, field workers said.

A dosimetre near the coast of Tomioka town, which measures the level of radiation in the area. A level of less than 0.1 μSv/h is considered normal.

Besides the lasting trauma of the triple catastrophe, the victims now have to grapple with lost friendships after the community they formed at their interim homes dissolved.

A 2019 study led by researchers from the Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine published in BMJ Open found that a greater percentage of survivors who moved from temporary housing to their new homes faced social isolation, which has been known to lead to depression and suicide.

Asahi Shimbun reported a growing number of people dying alone in these permanent houses, particularly among men.

Both articles reasoned that these new dwellings provide greater privacy, so neighbours interact less with one another. Social events have become infrequent as well.

One group of local missionaries trying to address the issue of loneliness in the evacuation zone are three sisters from the Catholic order the Sisters of the Visitation.

In 2011, they moved up to Miyagi prefecture from their base in Kamakura city to serve in relief efforts.

After three years, when the physical needs dwindled, they made a decision to stay and serve, eventually finding a home in Naraha, the town south of Tomioka.

The nuns moved to Naraha to offer a ministry of presence.

Returnees who have lived in Naraha for generations found the newcomers suspicious at first, but the nuns pushed through by joining the activities at the newly-built community hall, making small talk at the local clinic and train station.

The owner of a local bakery called Algernon was one of those who said she was grateful for the visits the nuns paid to her elderly father.

The three nuns hope that by offering their ministry of presence, the locals will open up about their sorrows and feel less downcast in their solitude.

Being an all-female team, the nuns face difficulty reaching out to the men in town, whom they say have become disengaged since moving back. Having lost their previous homes and farmland, there is no reason to leave their apartments anymore, they said.

The nuns showing their finished product from a recent community indigo dye workshop they participated in.

Lifted out of brokenness

At the same time, it is in the wilderness that God can reveal his might by rescuing the broken (Psalm 25:10).

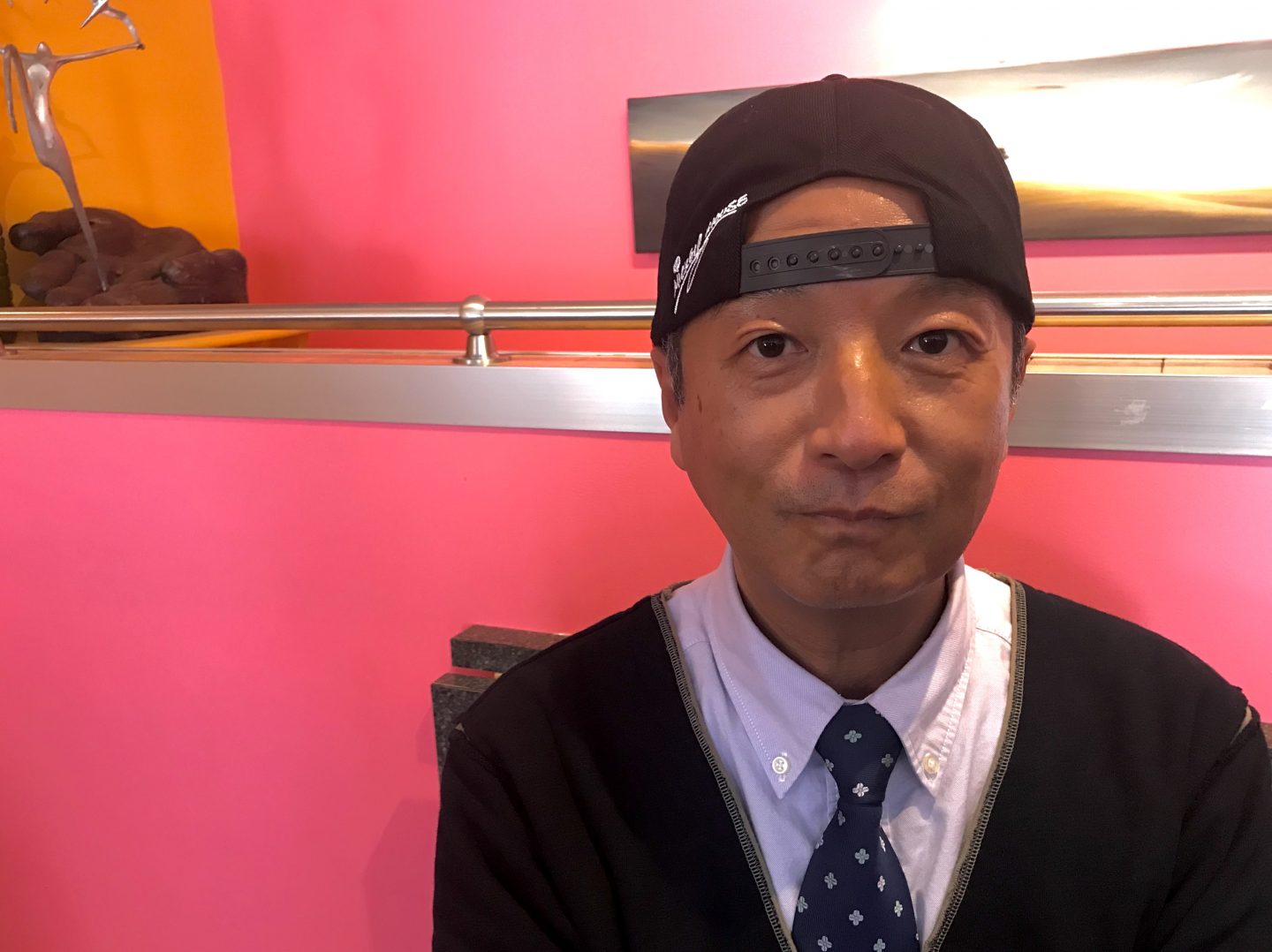

Kei Sato, 51, is one of the evacuees from Fukushima. Originally from Minamisoma, he left his hometown permanently after he lost all he had – his car, home, farm, mother and fiancée.

He is still sad about losing his closest ones, Sato said, but he also knew his preservation meant God had something for him to do.

One day when he was standing amidst the ruins on the beach, crying, he heard God tell him: “From now on, you care for others.”

Kei Sato moved to Chiba prefecture after losing everything, including his mother and his fiancee, in the tsunami.

Sato moved to Chiba prefecture, next to Tokyo, where he leased two plots of land to harvest vegetables and send uncontaminated produce to the elementary schools in Fukushima, and volunteered with a homeless ministry in Tokyo.

Pastor Toyomi Sanga of Grace Garden Chapel in Koriyama, a city 60km east of Daiichi, believes the time has finally come – eight years after the tragedy – for churches to “fill the spiritual void”.

The pastor told him there was no sin God couldn’t forgive … The man never killed himself.

With hype for next year’s Tokyo Olympics building up, she feels that the situation in Fukushima could be pushed aside. The prefecture’s residents need to know that they haven’t been forgotten, and it is the Christians who should step up.

Though the “disaster continues”, as one pastor puts it, all of them have been able to discern its upside: Unity among churches in a system once divided by denominations, recognition from the global church, and the opportunity to sow seeds even if the current generation doesn’t change.

Pastor Yoshiya Kondo was in Morioka city, Iwate, when the calamity occurred where he is the pastor of Morioka Bible Bapist Church. Iwate prefecture was affected by the tsunami and earthquake but not the radioactive fallout.

But news from Fukushima hit home hard – Pastor Kondo is originally from Okuma, one of the two towns that flanks Daiichi. Like the homes there, he noticed during brief visits back that his family home had been ravaged by wild boars. His home church Fukushima First Baptist Church, which sent him to Morioka 15 years ago, had to uproot itself to Iwaki.

Pastor Yoshiya Kondo started a church network days after the disaster to coordinate relief efforts in Iwate prefecture.

Yet, Pastor Kondo quickly mobilised himself. With four other pastors, he set up the 3.11 Iwate Church Network 13 days after the disaster happened.

News about the network spread, and other field workers joined to see how they could coordinate and participate in relief activities, regardless of their denomination.

Christian agencies also started sending their missionaries to Japan, a country where organisations were reluctant to send their workers to due to its barrenness. Since 2011, the 3.11 network has known more than 100 missionaries who have come (and go) to Iwate, Pastor Kondo said. JEMA’s figures show that there were zero missionaries in Iwate before the disaster in 2010, nine in 2012 and today, 24.

Our part to play

And with a growing Christian presence comes a softer view towards Christianity. Pastor Kondo speaks from experience.

The network was looking to set up several bases for their relief operations along the Iwate coastline. In Ofunato city, one home owner backed out after learning that the organisation was a Christian one. But another survivor stepped in and offered his place for a rental fee of just 2,000 yen (about S$25) a month.

Pastor Kondo wondered aloud why the survivor would rent his place out for so little.

Believers in Singapore can consider not just feeding the poor (Matthew 25:35-40) but also seeking the lost (Luke 19:10) in all nations.

The man said that in junior high school 60 years ago, it was an American missionary who had taught him English. This left him with a positive impression of the faith. When he heard that Christians were helping in Ofunato, he wanted to play his part.

He and Pastor Kondo struck up a friendship, and the man opened up to him, divulging that he wanted to die because he was ashamed of his past life and he didn’t have hope for the future. The pastor told him there was no sin God couldn’t forgive. It was also the Lord who led him to reflect on his life.

The man never killed himself. When he was in hospital, he would call Pastor Kondo for prayer. He eventually moved to a nursing home in Aomori prefecture, where Pastor Kondo visited him before he died. There was a Bible by his bedside.

Pastor Kondo said the man never confessed to believe in Christ. “But I trust God’s hand,” he said, mulling over the special bond they had.

Even after the catastrophe, Japan is still undeniably a wealthy nation. Temporary housing was quickly offered to the victims, followed by permanent ones and monetary compensation. The disasters in Aceh and Haiti killed at least 10 times more people, likely due to disparity in structural engineering and preparedness.

So why bother to help a developed country, seven hours away by air, compared to taking a ferry south of Singapore?

I posed a similar question to an American missionary during my pit stop in Tokyo: Was it difficult to raise funds for an “expensive” place like Japan? He said no, once donors recognised it isn’t about the physical, but about lostness.

Okuma town, which hosted evacuees from Daiichi with Futaba town, remains mostly closed to the public. Signs and barricades are up to prevent people from entering, and there is heavy police presence along the main road.

The Japanese are the second-most unreached population in the world. It is known to “chew missionaries alive”, as one former field worker said.

Pastor Kondo recalls that pre-3.11, Christian leaders told him they were reluctant to send their missionaries to Japan, as they wouldn’t be able to send “positive reports” back to their donors.

As the world continues to recognise the grief and misery in Japan, believers in Singapore can consider not just feeding the poor (Matthew 25:35-40) but also seeking the lost (Luke 19:10) in all nations.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light