Former Apple engineer trades prestigious job for bedbugs and broomsticks at Habitat for Humanity

by Janice Tai // July 23, 2021, 11:08 am

Hands-on: Habitat for Humanity Singapore's National Director, Yong Teck Meng, participates in the building projects he organises, like this one in Krabi, Thailand, in 2018. All photos courtesy of Yong Teck Meng.

Not many people know that Habitat for Humanity Singapore’s Yong Teck Meng wasn’t always working in the dirt.

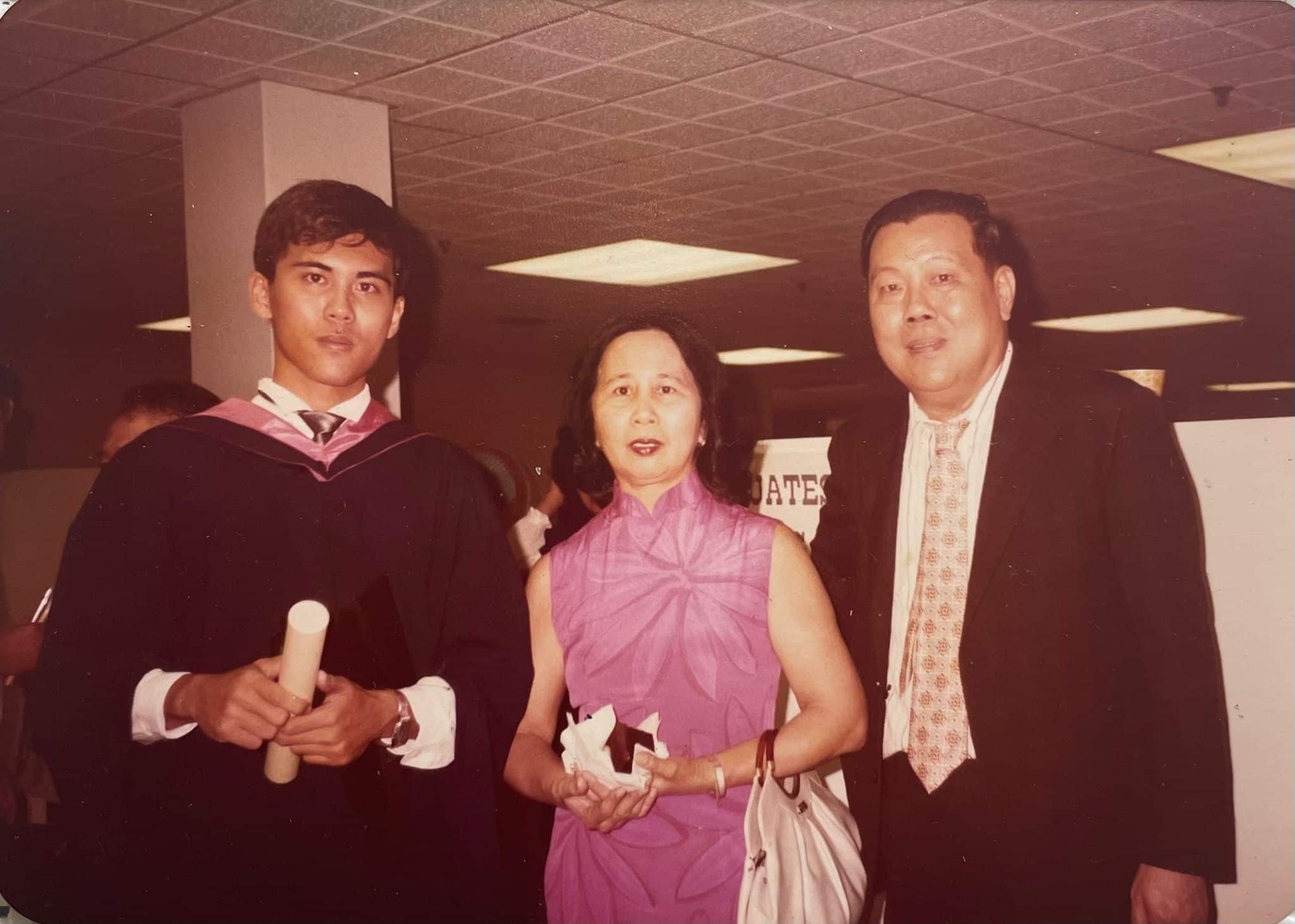

The Rafflesian had his pick of the hottest tech jobs available when he returned from his studies in the States in the late-80s, armed with an engineering degree from an American university.

He went with computing giant Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), then was headhunted by Apple Computer Singapore in 1990 and handed a cushy position as product manager.

Back then, Apple was not yet one of the world’s most valuable companies as it is now; even so, it was hailed as a pioneering and prestigious place to work in.

Cubicles were lined with Herman Miller furniture and robots would transport things from one part of the futuristic office to another. A popcorn cart would shuttle around the desks in the middle of the day and there would invariably be an ice cream party, or beer or satay party, every Friday.

All employees, whether head honcho or cleaner, was entitled to buy a Mac at $2,000 (retailing at $14,000 then) and could get seven weeks of sabbatical leave after working five years for the company.

But 10 years changed Yong – and his outlook on his future.

Solid ground: Yong helping to build houses in Krabi, Thailand, in 2018.

All things new marked the turn of the millennium, and in what seemed like the blink of an eye, he was cleaning up rental flats of the elderly that had bedbug tracks adorning the walls and dried faeces lining the floor.

His job title: National Director of Habitat for Humanity Singapore, a non-profit organisation known for building houses in disaster-ridden areas abroad and providing other humanitarian aid.

Empathy quotient

It wasn’t an unforeseen outcome.

“I didn’t see why we had to be only concerned about our own happiness and not the happiness of others.”

Yong came from a poor family and grew up in a kampung. When he was five, he noticed that the street vendor peddling sugarcane juice no longer had to grind the cane by hand as he had acquired a new machine that was able to crush it.

Overjoyed for the man, Yong dashed home to tell the adults the happy news. The response he received was apathetic: “Why do you care about that? What has that got to do with you?”

Then and there, young Yong imbibed the life lesson that his capacity for empathy was unique. “In Mandarin, there is a saying: 独乐乐不如众乐乐 (the happiness of a group triumphs individual happiness).

“I didn’t see why we had to be only concerned about our own happiness and not the happiness of others. I strengthened my resolve not to live life just for myself and my own happiness.”

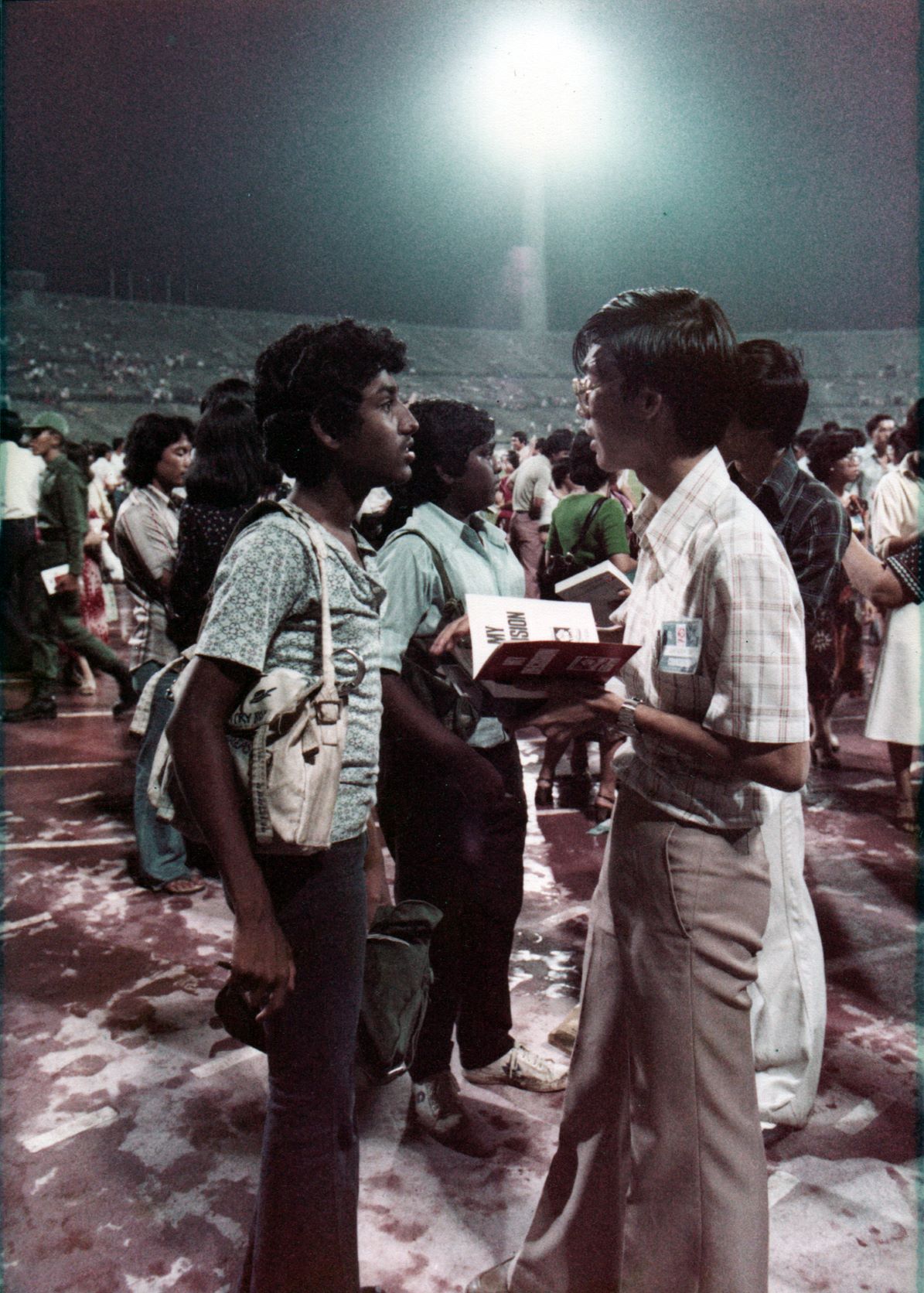

Bold witness: Yong as a teenager sharing the gospel with people who responded to the altar call at the Billy Graham Crusade in Singapore in 1978.

His tender heart would experience a greater awakening – and disillusionment – during his National Service stint, when he was posted to the Philippines for a special forward air controller course.

There in a place called Angeles City, Yong witnessed debilitating poverty. Observing a long row of gambling and prostitution dens, for instance, he saw American soldiers throwing pesos on the ground and children rushing forward to grab the coins.

In the bars, young girls would gyrate and dance in front of men, hoping to seduce them in return for some tips. Some were “adopted” by the soldiers as “wives”.

When Yong asked one of them what would happen to his “girl” when he returned to the US after his three-year posting, the nonchalant reply was: “She was off the streets for three years, now it’s time for her to go back.”

Sickened, Yong wondered: “What’s happening? What’s all this about? Why do people here have to live like this?” He knew he could not do nothing about it.

The altar call

He took this unease with him to the US, where he spent his undergraduate years. Serving in a church called Hyde Park Baptist Church as a youth leader, he took groups out frequently to visit the neighbourhood’s elderly.

Yong was also the church pastor’s resident translator for its mainly American-born Chinese congregation.

“Jesus was asking me then whether I had the compassion to be a shepherd.”

In December 1986, however, he found himself able to sit in the pews instead of having to translate the sermon live, because the congregation had gone home for Christmas.

The church hall was near-empty, and the pastor was droning on about Matthew 9:37. To prevent himself from falling asleep, Yong turned to the Bible passage, but his eyes landed on the preceding verse.

He read that it was in the context of Jesus seeing the crowds and having compassion on them – “because they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd” – that He told His disciples to ask God for more workers to tend to the harvest.

“Jesus was asking me then whether I understood that the people around me were harassed and helpless, and whether I had the compassion to be a shepherd,” said Yong, his voice breaking as he recounted the call he received 35 years ago.

He raised his hand at the altar call, and his pastor was shocked.

A certain breakthrough: Wong speaking at his ordination ceremony in 2016.

Yong’s father, too, was shocked when, upon returning to Singapore, Yong spoke of his desire to go into full-time ministry. The older man cried. It was the first time Yong had seen his father cry, and they weren’t tears of joy.

Yong’s father had paid for his overseas education, and it was his hope that his son would make “good use” of his engineering degree. Not wanting to disappoint his father – and to give him at least a few years of “bragging rights”, Yong joked – he took up those plum jobs at DEC and Apple. They had, after all, the “multi-national corporation” branding.

Marketplace minister

Doing so did not mean Yong had turned his back on God. He felt he could still honour God by doing his best in the secular world. He became the youngest senior engineer at DEC. Studying part-time for a graduate diploma in theology at the Biblical Graduate School of Theology, he graduated with summa cum laude.

When Community Chest began seeking working professionals to help it raise funds from their peers, he was the first person in his office to volunteer to be seconded to the charity for the task.

He turned out to be an excellent fundraiser – partly due to his thick skin, but mostly due to his diligence. His job involved going to various workplaces to publicise the ComChest fundraising scheme and convince working adults to donate a small part of their salary – say, $5 – monthly.

“Sometimes, the lower the positions the workers are in, the more money they give.”

Nobody wanted to take up the 7am or midnight slots, except Yong. He figured out that being at the Japanese factories at 7am was the best time to talk to the bosses before they buried themselves in work. At midnight, he would go to the bars to talk to the bar girls and get them to donate.

“I preferred to go to the factories and bars. You learn very quickly in fundraising that sometimes, the lower the positions the workers are in, the more money they give. I didn’t like to go to law firms as the lawyers will ask many questions about the scheme but end up not giving a cent.”

In 1989, at 27, Yong received the Special Volunteer Award from then-President Wee Kim Wee on behalf of ComChest. He continued to volunteer for many years and later also received a long service award.

At the age of 33, he left Apple to strike out on his own. A former colleague, who’d noticed an animated film he’d done, convinced him to ride the dot.com wave and start a company doing animated children’s books.

Yong was on the cusp of getting his company listed in Hong Kong in 2001 when the September 11 terrorist attacks happened in the US. The fallout tanked his hopes.

He went on to dabble in running a private school, a corporate training outfit and a listing agency in China – none of which took off.

Peace like a river: Yong and his family holidaying in Japan in 2019. His wife runs a social enterprise.

The serial entrepreneur had two daughters by then. Riddled by anxiety about providing for his family, he learnt that following God’s leading and guidance was not always a guarantee of success. Neither was it assurance that things would go smoothly.

“In Luke 4:1, it was the Holy Spirit that led Jesus to be tested by the Devil.

“I have learnt to commit every single decision I make to God and even if things don’t turn out the way I hoped, I am at peace that He is leading me and He allowed it to happen,” said Yong.

Rising up

In the early 2000s, a fellow ComChest volunteer who had joined Habitat For Humanity International asked Yong to set up a local chapter. “Make it happen,” she challenged him.

He devoured a copy of Habitat founder Millard Fuller’s The Theology of the Hammer, and was sold. Its many biblical ideas resonated with him – like Fuller’s principle of win-win acts of service in the “economy of Jesus”, in which both the giver and beneficiary gain from the interaction and the beneficiary also is empowered to give back.

Staff bonding: Yong put his hands to the shovel for a building project in Batam, Indonesia, in 2019, in which all staff members were encouraged to participate in the actual work of building houses.

Future hope: Yong taking pains to level cement in a housing project in Chiang Mai, Thailand, in 2009.

“In all of Habitat’s projects, we encourage the beneficiaries to ‘pay back’ in some way, so that the model is sustainable. It could be a form of ‘sweat equity’ in which they chip in to build or clean their own house, or they could also donate a token sum to defray expenses,” Yong described.

“We are not giving a handout but encouraging people to put their ‘hands up’ to serve one another.”

“This is an important principle, because then it becomes a catalyst to promote serving each other and there is interdependency. We are not giving a handout but encouraging people to put their ‘hands up’ to serve one another.”

Waves of change

The Indian Ocean tsunami on Dec 24, 2004 revved things up.

Habitat Singapore – which had only one employee – received a US$8 million (S$9.8 million) infusion from the Singapore Red Cross for rebuilding efforts. Yong resigned as HHS’ volunteer chairman and became its full-time national director to oversee the construction of 1,700 houses and five wells in the devastated town of Meulaboh in Indonesia’s Aceh province.

After the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, it got another US$7 million boost. It spent less than half erecting 875 houses and a nursery in Chengdu and returned the unused money.

Both times, Habitat Singapore was hailed for its exemplary fund management. Yong said they continually tapped on God’s wisdom to make full use of every cent of the donations that came in. Through His favour, HHS in the course of its extensive work was also able to circumnavigate the corrupt practices of many developing countries.

In the meantime, Yong had steered Habitat Singapore onto new ground locally. During a 2006 home visit to a flat in Bukit Merah, he found himself entering a room reeking of the stench of urine.

An old lady, who was paralysed from the waist down, sat on the bed. There were many brown stains on the wall behind her.

“It was like an abstract painting. How it happened was, the old lady would notice a bed bug and kill it against the wall, and its blood stain would turn brown over time. She was also not mobile and defecated in her bed,” said Yong.

The scene was deeply disturbing to Yong. He kept thinking: “How could we leave the elderly woman to live like that, knowing that God had created her?”

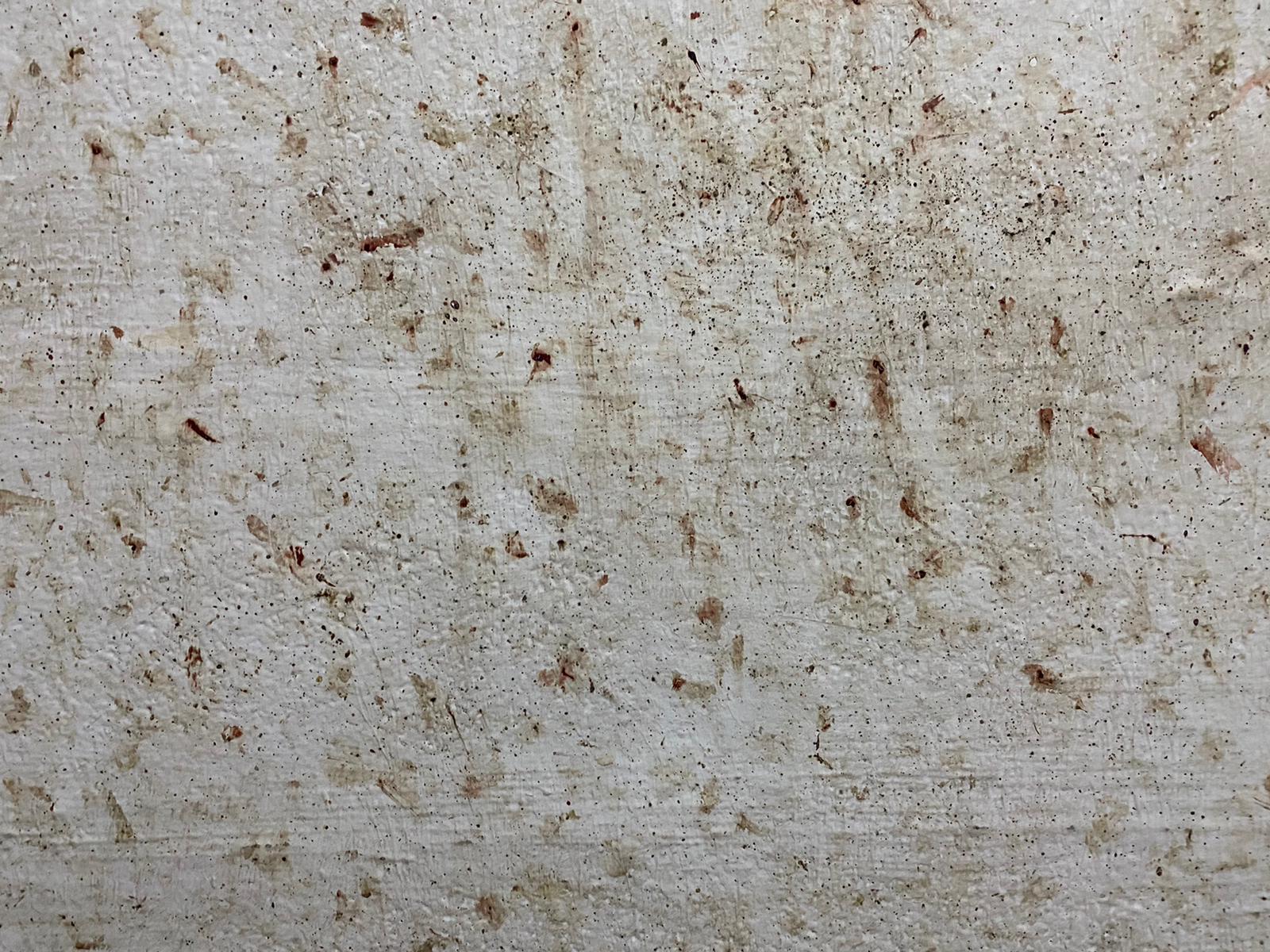

Marks of neglect: A Chinatown home infested with bedbugs is among those HHS has cleaned up.

That night, he happened to be invited to share the word of God with a group of Christian leaders. He preached on the parable of the sheep and goats (Matthew 25:31-46). Giving the real-life scenario of the old lady he had met in the day, he broke the leaders up into groups to discuss an action plan.

The first group said inequality was a complicated societal issue, adding that they were there to study God’s Word and the matter was not on their list of “KPIs” because they had no capacity to handle it. The second group agreed.

The third group observed that this was a long-term issue and more suited to those with the gift of compassion. The fourth group insisted that it was not that they did not want to do something but they were otherwise committed to short-term mission work in Thailand.

“As they gave me their responses, I would say the same thing back to them. ‘Yes, but the old woman is still lying on that bed.’

“Actually, it is not that complicated. Since the woman was lying in filth, everyone could chip in to provide her with adult diapers that cost about $76 a month.

“Then, they could also arrange for her home to be fumigated. It is not that they could not do something, but that they would not.”

No conclusion from the discussion was reached that night. Two weeks later, the old woman died.

Not wanting to be an “ivory tower theologian” – who preached the Word but little else – Yong started Habitat Singapore’s Project Homeworks. After consent is obtained, volunteers go into the flats of the destitute elderly to scrub, mop and fumigate.

Use your hands: Yong helps out in Project Homeworks as well.

Project Homeworks does about 300 cleanups a year, up from 100 when it first started. The non-profit organisation, which also does other projects apart from Project Homeworks, operates on donations of some $1.3 million a year. More than 80 per cent of those they serve are elderly, many with mental health issues.

“Everyone, no matter how poor or weak, has the capacity to help others,” Yong emphasised, citing James 2:17 and telling of an 80-year-old elderly woman whom his church helped to support with a $500 allowance: She recently took in an abandoned 90-year-old lady to live with her.

Art therapy: In 2015, Yong and HHS volunteers taught the residents of Ling Kwang Home to produce artwork for sale to support the nursing home.

Building lives

Now also a pastor at Reformed Evangelical Church, Yong is additionally the Chaplain for Far East Organisation, the largest private property developer in Singapore.

“It takes great courage to be known as a Christian enterprise, though its employees can be of various faiths. Many businesses don’t want to, because they know they have to lose some freedom and may be exposed for their hypocrisy.

“So, it is not easy but if we succeed, then we can be a model for others to follow.”

Bare Your Sole: Habitat for Humanity Singapore’s annual barefoot fundraising and advocacy campaign in 2016 included the participation of Far East CEO, Philip Ng (second from right).

His role is to uphold the conscience of the company by – for instance – ensuring responsible advertisements and appropriate staff behaviour. He provides counselling and pastoral care for all faiths and is a neutral voice for grievances of employees.

He runs the daily devotions and Friday chapel service as well. “You discover that a lot of people don’t want to be Christian during the week days,” he said with a smile.

Different strokes: Yong relaxes by imitating painting’s masters, usually Impressionists. His latest is a replica of Claude Monet’s ‘Walk by the Cliff at Pourvelle’.

To relax, Yong does oil paintings, sculpturing and other crafts. “There is no need to strive. We are already the salt and light that God has created us to be. We just need to be obedient and do what we were made for.”

In that vein, he continues his interpreting work and is the translator for Indonesian evangelist Stephen Tong, whom he has worked with for a long time. He has also translated for international speakers such as Timothy Keller.

An instructed tongue: Yong is Indonesian evangelist Stephen Tong’s Mandarin translator.

Yong translated for American pastor and apologist Timothy Keller at a conference in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, in 2019.

The abundant life

Though Yong is preparing HHS for leadership succession as part of its regular renewal, he plans to continue to serve there till the day he dies.

“I am blessed that the Lord has made me who I am, so I enjoy everything that I do. It has been a multi-faceted life and I want to live the abundant life that Jesus promised us in John 10:10,” said Yong, whose wife runs a social enterprise.

The builder remains true to his roots. The Covid-19 pandemic has prevented him and his team from doing much building overseas these days, but he continues to get his hands dirty cleaning homes in Singapore.

Just last month (June 2021), he took another “abstract painting” photo of a wall full of brown stains in a house he helped to clean up.

Abstract art: Streaks of dried blood left on the walls of a bedbug-infested house that Yong helped to clean in June 2021.

“The photo will be framed up and placed in our conference room. It is to remind ourselves why we do what we do, which is about impacting lives in a tangible way. We need to be hands-on and in touch with the ground, and not lose focus.”

RELATED STORIES:

How do you love a child who is not your own? Parents who foster with the Father’s heart

Is the middle-class Church in Singapore getting too comfortable?

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light