“We need to change the whole way we do missions”: OM’s Global South Initiative director

by Christine Leow // December 22, 2021, 11:45 pm

Saw Seang Pin (in the middle) with former and current co-workers in OM GSI. Working with the global south missionaries was a "God thing" for Saw who, while open to new things, tended to pick the "safe" routes in life. Photo courtesy of Saw Seang Pin.

She is a missionary but she lives in Singapore. She is a missionary but she builds no schools, wells or toilets. She is a missionary but she plants no churches.

Saw Seang Pin, 54, is a missionary different from those with whom the world has become familiar – the First World believer sent to developing nations to preach to the unreached or those with no access to the Gospel.

Her work as the Director of Operation Mobilisation’s Global South Initiative (OM GSI) is a response to the changing face of the Church.

“I like working in an environment where you are doing new stuff.”

A century ago, about two-thirds of Christians came from Europe; the rest were from America. By 2030, 80% of the world’s believers will be in the “global south” or “majority world”, terms for that region of nations formerly known as “Third World” or “developing”.

This means Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and much of Asia will have the largest pool of potential missionaries. Saw’s team intends to empower these people to share the Gospel.

It is unchartered territory, but Saw relishes the challenge: “I like working in an environment where you are doing new stuff.”

New beginnings

Yet for most of her life, Saw went for the conventional. She chose to read law, a conventional choice, and started her career practising corporate law in a big law firm – another safe choice.

She landed her next job at the in-house legal department of an international bank not by design but purely by circumstance. This turn in her career would start her on the road away from the tried and tested.

Working in an investment bank introduced Saw to derivatives trading. A relatively new arena in the 90s when she started in it, derivatives trading would develop into one of the most innovative and fast-paced branches of investment banking.

“I was thinking: ‘This is a bit meaningless that I am working so hard just to make more money.’ ”

This played to Saw’s strengths: “I don’t like to do the same thing over and over again. I’m the type of person who really has to do new things.”

She would spend the next decade in investment banking. But before she turned 40, she was burnt out.

“I started to ask myself, ‘What is this really for?’ It was not a very good theology of work (at that time) but I was thinking: ‘This is a bit meaningless that I am working so hard just to make more money.’ ”

She now believes that doing a job well is itself meaningful. But the “extreme reaction” to her environment back then was just the right push to make her re-think her career.

Ripple effects

On Boxing Day 2004, a tsunami hit various parts of Asia, sending 30-metre waves crashing onto coastal areas in 18 countries. Nearly 230,000 people were killed and 1.7 million made homeless. It remains one of the most devastating natural disasters in history.

Saw found herself more interested in thinking about what was sustainable relief for the victims than in her job.

“I wasn’t reading the Financial Times before bed. I was researching and reading up on disaster response and thinking about how best to help: Do you send money, and if so who to? Should you send used clothes? And the answer to that is ‘No’!

The 2004 tsunami that devastated many parts of the Asia got Saw thinking about sustainable relief and a career change. Photo by Debbie Meroff (OM).

“I was caught up in questions of how best to help people. I started thinking: Can I make this my life? Can I give up my secure job in banking?”

So began a serious search for a job in the non-profit space. Saw insists the move was a God thing because, while she enjoyed encountering the new, she had always leaned towards the more established paths in life.

“I knew I had to start at the bottom – which is what you do when you change course and know nothing.”

Nothing turned up with non-profit organisations but an opportunity arose in leadership development with a mission organisation.

Working in missions was never on Saw’s agenda because of her husband’s work commitments in Singapore. She is married to Reginald Tan, a professor of chemical engineering with the National University of Singapore (NUS) and the Executive Director of Science and Technology Research at A*STAR.

But she took up the job anyway, even though it was an administrative position that came with only a modest allowance.

“I knew I had to start at the bottom – which is what you do when you change course and know nothing. So, I was willing to do the hard work and learn from scratch.”

So big was the drop in her salary that, months after, a tele-marketeer calling to offer her a new credit card hung up when she heard that Saw was no longer earning a decent salary.

“She didn’t even say, ‘Sorry.’ Tele-marketeers are now hanging up on me! I had become such a nobody,” says Saw with a laugh.

But she did not mind. “All along, I was never really into all that money. My husband and I don’t live the luxe life.”

Personal discoveries

Her new job required her to tidy up PowerPoint slides for leadership training workshops. Though she enjoyed it, Saw would soon discover that she had a knack for training. It was not long before she started conducting the workshops.

“I fell into a lot of things,” she muses. “God was just there protecting me even though I had no idea how or what to do in missions. God landed me in all the right places.”

“God was just there protecting me even though I had no idea how or what to do in missions.”

Ten years on, though, Saw would again be looking for a new job.

“I was stuck in Singapore. So, my options were limited. I tried mobilising for a bit, sending short-term mission trippers to serve as professionals on fields closed to the missionaries.

“But that job, while rewarding, was too routine. I found that even in mission life, if I was in a job that stayed the same, I would get bored very fast. I had to move on.”

At first, Saw tried setting up a leadership development consultancy for non-profit organisations. “It really wasn’t my intention to join another mission agency.”

That was why, when a church friend who worked with Operation Mobilisation (OM) mentioned an opening, Saw did not consider it.

Then, her business plan fell through. “I went on my own adventure. Only when my own adventure crashed did I go back to ask her (about the job).”

She learnt more about the work to bring believers from the global south into the mission field. It was future-forward work that required breaking traditional models of missions.

“The project was just too interesting to pass up on. I joined their vision of the project.”

That was how she ended up at OM.

The work of integration

Within a year of Saw joining the team, the original three-pronged approach of looking at organisational structure and culture, promoting leadership development for global south missionaries, and ensuring financial sustainability was sharpened to focus on business as mission.

The objective was to equip global south missionaries with the skills and start-up funding to run businesses as a means of outreach as well as a source of financial sustainability.

Asked how this form of missions works, Saw talks about integration. This is when a missionary chooses a business that allows plenty of people-contact. Gig businesses such as wedding photography, and tailor and barber shops are good options, as are sports and gyms.

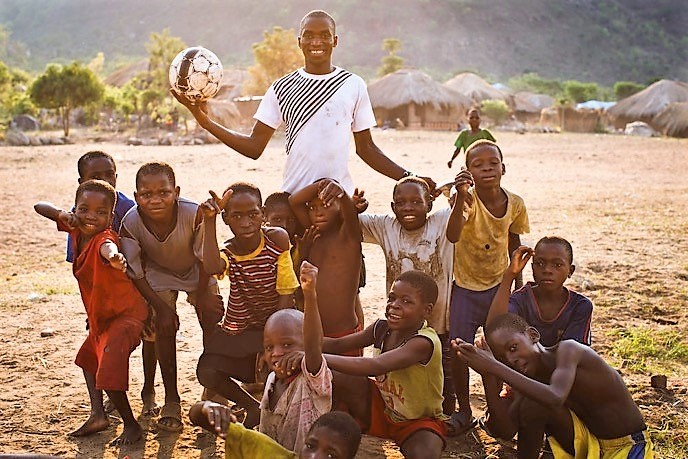

A soccer coach and his team in a ministry in OM Africa. This is part of the business-as-missions model at OM. Photo by Brad Livengood (OM).

“In sports, people build bonds and relationships. There is a lot of mentoring. You learn life values. When people are interested in wellness, how to do better, how to live better lives, it is easier to slide in the Gospel.”

“When people are interested in how to live better lives, it is easier to slide in the Gospel.”

Which is how God’s Word is shared. As the missionaries go about their work or life, they weave the Gospel into their conversations.

“You tell them Bible stories. You ask, ‘How is your life?’ They tell you and you say, ‘Let me pray for you. Let me tell you about Jesus. We can meet at my house and I can tell you more.’

“That becomes the Bible study group that forms the foundation of your church. So, from the start, you train them to look at the Bible, hear from God and learn how to put it into practice in their lives. And you do it even with non-believers.”

Organic farming takes off

One particularly successful OM business in Asia that has incorporated business and the Bible has been organic farming. In one Asian capital, organic farming took off because there were plenty of tourists as well as restaurants, ensuring constant demand.

The farm also teaches farming methods with “God’s story woven into it”, Saw explains.

Farmers planting crops in an OM business in South Asia where Christian farmers share how God is evident in their farming, which then becomes a way to spread the Gospel. Photo by Rebecca Rempel (OM).

“It is good farming methodology that is biblical: You pray for crops, rely on God’s provision, don’t exploit the land but let the land breathe. It’s a live demonstration of stewardship and dependence on God.

“If the neighbours ask, then you can share how you pray and God sends the rain, or how God’s soil is sufficient for you.”

Armed with these farming skills, the missionaries are sent to rural regions to use farming as an evangelistic tool. If it sounds a lot like being a Christian in the marketplace, it is. What makes it missions is that it is done intentionally and among the least reached.

Lessons from the global south

The GSI team has had to be innovative and flexible, ready to learn quickly and change course – everything Saw enjoys doing.

At one point, they thought that focusing on just a few business ideas might be better than trying out too many different ones. But they discovered that narrowing choices did not get them very far.

“We tried chicken farm ‘franchising’ because chicken is quite universal – everyone eats chicken. But we found that small-scale chicken farming does not work everywhere. In one country in Africa where we tried it, we could not compete with the big chicken farms in the area.

OM GSI supports chicken farming projects like this one in Africa. Photo courtesy of Saw Seang Pin.

“We realised that it is hard to ‘franchise’ business because it is contextually sensitive – even farming. You have to consider where is your farm, which part of the country it is in, where is the nearest market, the nearest main road, the type of soil.”

The team had to pivot to customising rather than standardising.

So, the team had to backtrack on this strategy and pivot to customising rather than standardising.

“Telling them what business they should start doesn’t work. Unless it is an idea that the people themselves are passionate about, the business would fizzle out in a matter of months.”

The other lesson learnt is to start small, “because when they are big, when they fail, they fail big.

“They lose heart and resources and don’t know what to do next.”

“Anybody can”

The businesses that did eventually thrive were often small ones that arose from personal interests. One woman chose to sell cosmetics because that was her passion. Her business did well.

So, now the question they ask their missionaries is: “What is in your hand?”

“Think small, think of your own interests, what your parents did, what you are familiar with in your own hometown. Very often, we help them discover what they can do.”

That was how another missionary landed on the idea of growing roses to supply to florists. Her parents had grown flowers in her home country.

Saw points out that such a model allows for anyone who is willing to become a missionary. “I was struck by the vision of ‘anybody can’.

Missions to the global south demands a re-thinking of the traditional “West to the Rest” model.

“When we think about missionaries, we often think about the ‘haves’ going to the ‘have-nots’. Our mental image is of Christians – usually Western – going with their education, expertise, wealth, resources, and Christian traditions and know-how to save people who lack these things.

“This is a bit of a caricature of what happened when missions was from the West to the Rest (of the world),” explains Saw.

Missions to the global south demands a re-thinking of this traditional model.

“We must be open to many more mission models, such as Kenyans going to Japan as nurses, English-as-second-language teachers, hip-hop dance teachers, or business people.

“It cannot be that the Kingdom of God can only be extended by atas (posh) people. (For me), it’s a bit of a justice issue.

“Justice demands that God’s mission force not exclude believers who may not have fancy degrees from First World countries, but love Jesus and have the gift of evangelism.”

These missionaries, Saw maintains, would also be more relatable to the unreached people of the world. “Who is best able to reach the unreached nomadic herder in Mongolia or trek in South Asia to live in the villages to tell them about Jesus?”

This is truer to the biblical model of the Kingdom of God, says Saw.

Money issues

The other mindset shift when working with the global south concerns financial support. In the past, missionaries were expected to raise their own support.

“If we do missions in a way that doesn’t depend on having excess money, you can multiply.”

“Some of (the global south missionaries) don’t have churches who can support them. For example, they are first generation converts, or are in churches that are persecuted.

“Or they may come from communities where people don’t have disposable incomes, and they can’t raise support from friends and family. Everyone is struggling. How can you raise support?

“We are trying to send people who do not come with money. Anyway, even if you have the money, how many churches can you start if every church plant comes with a project such as a school that needs constant funding?

“But if we do missions in a way that doesn’t depend on having excess money, you can multiply.”

In true Saw fashion, there are more changes ahead for OM GSI.

“Maybe it’s ill-conceived to expect missionaries to be businessmen. Maybe we have to recruit missional businessmen because business is not for everyone,” she reflects.

“In any event, business is not a magic bullet. We can’t just try to increase input such as money into the same old ways that we do missions. But we need to change the whole way we do missions.”

This is where the work may be heading in the next few years. The hope is that the people in the global south will take the lead in this.

Saw does not yet know how they are going to pivot but she welcomes the challenge. “The most fun problems are those that can’t be solved in a few years.”

A paradigm shift ahead

The years at OM GSI have taught Saw well.

“I feel sad when people approach this issue from the standpoint of how we must lift the majority world, how we must help them because they are unable.

“They have a lot to give. They are very resilient. They pick themselves up when they fall. They know how to suffer. They can be very creative. They know how to get more done with less. They learn on their feet.”

A planner by nature, she has discovered that living without plans is “almost a spiritual discipline”.

Her African counterpart who fronts OM’s interactions with OM workers running businesses in that area has been her teacher in many ways. He has taught her to be more flexible. For example, going through some business applications, Saw would find some discrepancies.

“On one form you say $10 and on another you say $50. When I went to Brian, he told me to give them the benefit of the doubt.

“He told me, ‘Just because they can’t fill a form doesn’t mean they can’t run a business. Many market stalls do fine and they don’t use a single piece of paper’.”

Saw has also learnt to let go of schedules. A planner by nature, she has discovered that living without plans is “almost a spiritual discipline”.

“When we have meetings, the Africans are like, ‘See you at the conference!’ I’m like, ‘Yes, but when? Which day and what time?’

Sitting under a tree can be considered God’s work, too. This was an important lesson Saw learnt in building cross-cultural relationships. Photo courtesy of Saw Seang Pin.

“But their lives are really like this. They can be two days late for meetings because the border crossing took a day instead of 20 minutes because the office closed for the day.

“I’ve literally sat under a tree waiting and then some random person comes to chat with me. After a while, I realise that sitting under the tree is work, too.

“It is the meeting. It is how you get to meet people and find out what is going on. All because it’s a different way of doing things, doesn’t mean it doesn’t work.”

RELATED STORIES:

I was a failure but a family gave me a home; today I’m the National Director of YWAM Singapore

Would you let your daughter go to Congo and Rwanda? “It’s our honour,” say this missionary’s parents

Be Part of the Global South Outreach

The church in the global south is growing fast. Help OM mobilise the largest pool of missionaries in this part of the world and increase witness to those who have not heard of Jesus: www.omgsi.org

Follow OM Singapore on Instagram and Facebook.

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light