Almost two years on, a doctor at the heart of Covid care since the start reveals why he soldiers on

by Juleen Shaw // November 11, 2021, 12:36 am

Dr Malcolm Mahadevan (centre, in dark blue) and the team, with Ministers Gan Kim Yong and Lawrence Wong, co-chairs of the Multi-Ministry Task Force on Covid-19, at the Big Box Community Care Facility. All photos courtesy of Dr Malcolm Mahadevan.

Heart-pumping.

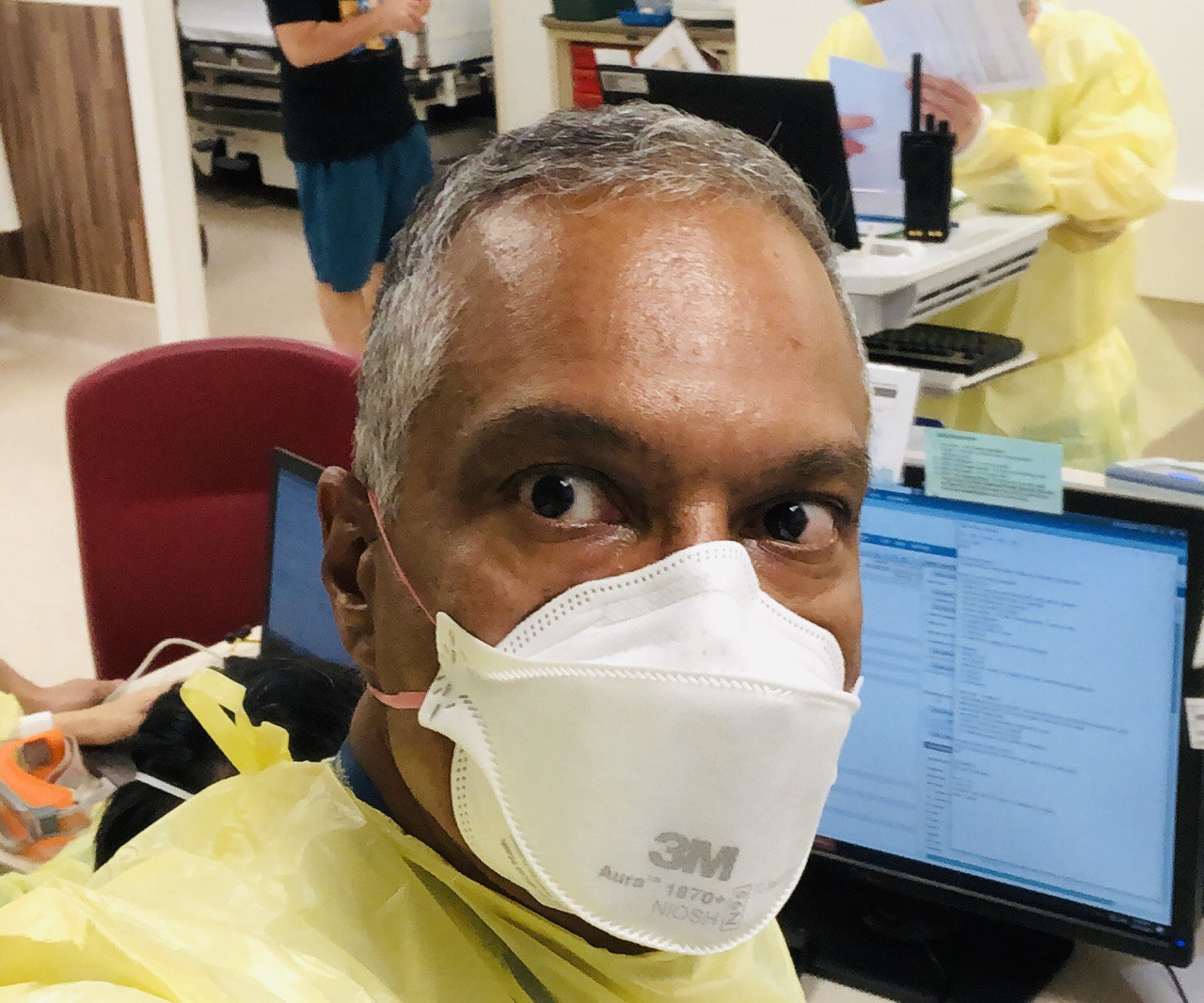

We might use the words flippantly to describe an action movie or a rollercoaster ride. But for emergency medicine specialist Dr Malcolm Mahadevan, 56, heart-pumping literally describes his every day for 26 years.

The Group Chief of Emergency Medicine at the National University Health System (NUHS), has a string of accolades to his name, including the Singapore Healthcare Humanity Awards 2015, and the Team National Medical Excellence Awards – not once, but twice – in 2012 and 2014.

His “classroom” for medical students and junior doctors includes, not just the NUS Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, but hospital waiting rooms and the emergency room floor, amidst distraught family members, screeching machines, clipped communication and urgent action.

Clearly, it takes someone who can handle the adrenaline.

“My sister laughs at me, because she says even when I was a child, five minutes before the bus arrives then I would get ready,” the amiable doctor told Salt&Light.

Dr Mahadevan (centre, in dark blue) and his team with Minister Lawrence Wong (third from right) at a fever facility in NUH.

The point was reiterated recently when some of his medical colleagues in non-emergency specialties dropped by his workplace. They told him: “Every time I come to your department, I feel stressed.”

“Why?”

“It’s all the sounds and all the activity,” they replied.

His “classroom” for junior doctors includes the emergency room floor, amidst screeching machines and urgent action.

“I realised that this is every day for us,” Dr Mahadevan reflected, “but for others, this kind of environment can cause concern.

“Being able to be in a tight situation and think through the situation is a gift,” admitted the Christian.

Nonetheless, two-and-a-half decades of hyper vigilance can wear a person down.

After 10 years as Head of the NUH Emergency Department, the senior consultant was nudging burnout last year.

His plan was to switch to a lower gear, stay useful and purposeful, but preferably not gunning his engine at top speed.

But, as God would have it, the plan itself changed gears.

Rise of a pandemic

When Covid started creeping into news headlines in January last year, Dr Mahadevan was in the UK.

“I was already reading about Covid in the papers,” he related. “The minute I returned in February, Covid was on everyone’s lips. By March, we were already capacity building in the emergency department. We’d had some experience with an epidemic – remember SARS – so we knew we had to start preparing early.”

Timing was everything in the rapidly-spreading pandemic.

The Government was moving quickly to repurpose industrial buildings to quarantine migrant workers and Covid-19 patients with milder symptoms. The move was meant to free up hospital capacity for patients with serious symptoms, and save as many lives in Singapore as possible.

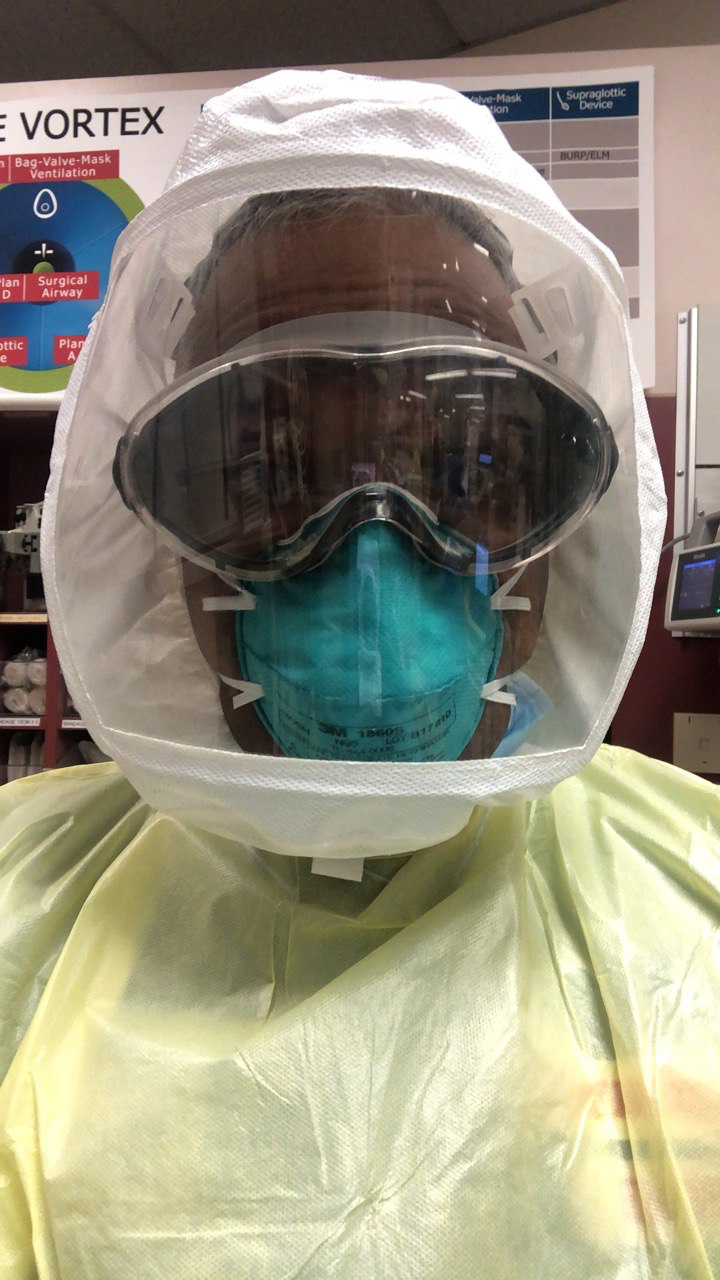

On his birthday in April 2020, Dr Mahadevan was not out celebrating, but suited up in full PPE at a migrant worker dorm.

This was a life-and-death scenario that Dr Mahadevan had faced for 26 years. He could not think of anything else more important at that moment than keeping people alive.

The lower gear would have to wait.

“That first dorm in Tengah had 25,000 workers in five blocks of something like HDB flats. It was very challenging.”

In a series of quick decisions, he stepped out of NUH to become the Medical Director in the task force setting up three dormitories for thousands of migrant workers in western Singapore. (The National Healthcare Group and Singhealth clusters would set up dormitories in central and eastern Singapore.)

On his birthday in April 2020, the doctor was not out celebrating, but was suited up in full PPE at a dorm, preparing to “go back to basic doctoring and caring for at-risk people”.

The task ahead was prodigious.

“That first dorm in Tengah had 25,000 workers in five blocks of something like HDB flats,” he recalled. “It was very challenging. We didn’t know where to start.”

The team of medical workers – some volunteers, others seconded from public hospitals and private healthcare operators – were to care for the workers here while new facilities were being refurbished.

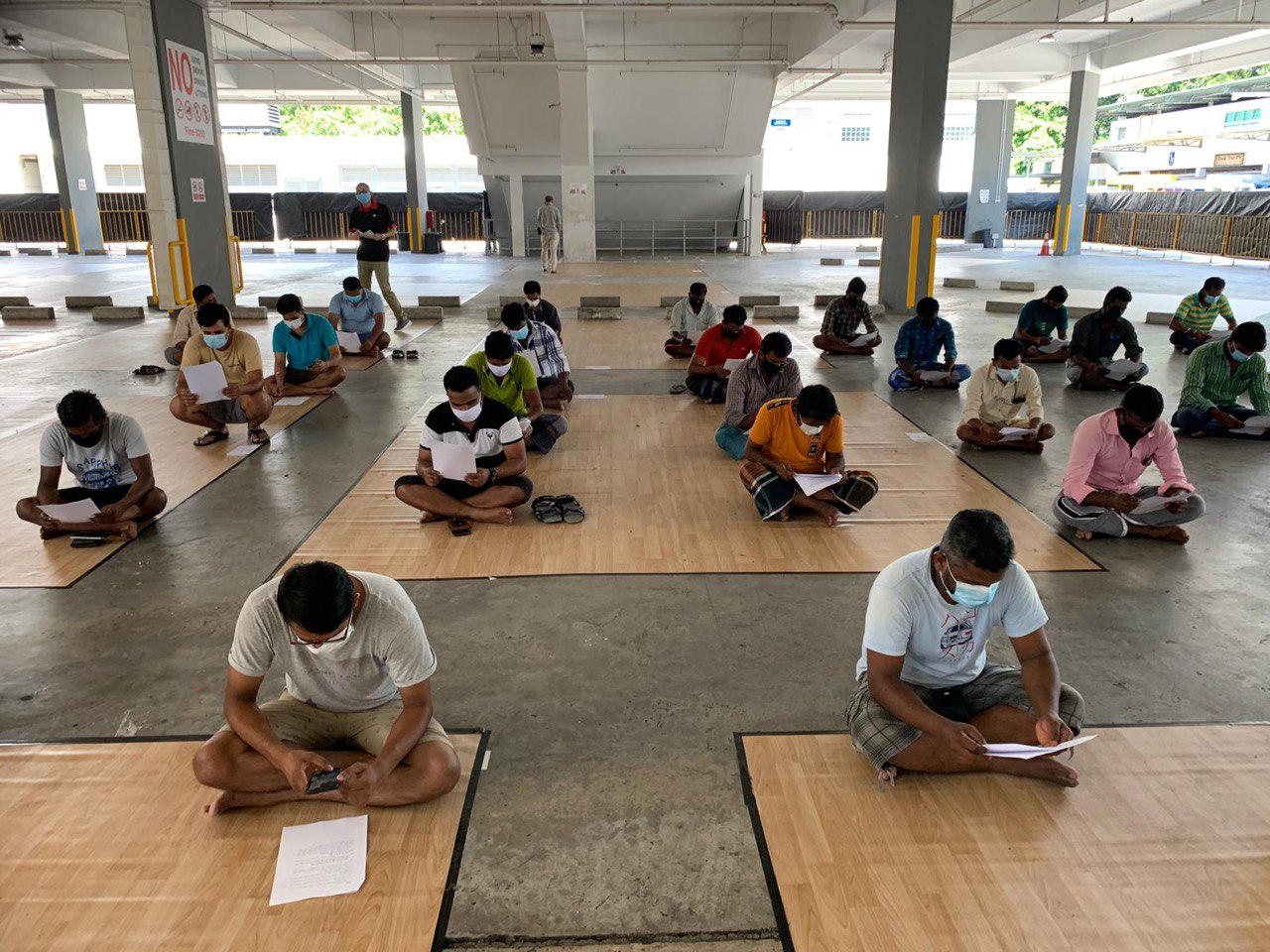

When he looked into the eyes of the thousands of workers, he saw that “everybody was scared”. The fear sometimes turned to anger – “it’s common, because when people don’t know what’s going on, they feel angry”.

“They’re young, they’re displaced from their country, they’re sick, they needed not just information but assurance,” said Dr Mahadevan of the quarantined migrant workers.

No one was prepared for how quickly Covid would spread among the workers. The living conditions of the workers became widely criticised.

Operating conditions in the dorms were also austere. Without air-conditioning, the doctors in their full PPE gear sweat so much that their goggles fogged up, and dehydration caused some to lose up to a litre of water.

“The situation was very tense. The police were there to ensure orderliness,” he said. “These workers were our patients. We had to win over their trust, somehow communicate to them that, ‘Hey guys, we need to start somewhere. Let’s work together.’”

Without air-conditioning at the migrant worker dormitories, the doctors in PPE sweat so much that their goggles fogged up.

The language barrier, the fear and the strange conditions made communication daunting.

“But we said, ‘Cannot lah, we have to engage with them.’ So through loudhailers we managed to get the leaders of the individual blocks to come down. HealthServe volunteer interpreters translated as I told the leaders, ‘We’re here to help you.’ We gave them handouts in their language to share with the rest.

“Somehow we had to try to convey our care and concern through non-verbal, as well as verbal means.”

The medical team believed that the workers would not become critically ill as there was a monitoring system in place. “But there were other things they were concerned about. They’re young, they’re displaced from their country, they’re sick, they needed not just information but assurance,” said Dr Mahadevan.

“Somehow we had to try to convey our care and concern through non-verbal, as well as verbal means.”

“We asked them what was important to them. They said wifi. So we included that. We asked HealthServe what the workers enjoy doing to relax and they said carrom, so we put carrom boards on every floor.”

Every fortnight, the team would ask the workers questions that would reveal if any were depressed so that help could be offered.

“One day they had an unusual request,” he related. “They said, ‘Can we play cricket?’ We apologised that we couldn’t give them bats (it was a security concern). But we felt really sorry for them and we said, ‘We can give you balls!’ And they were so happy.

“The majority of the workers were very appreciative because they could see that we were all trying.”

Through the entire experience, the medical team was humbled time and again.

“It was such a learning experience. Mistakes were made, like with their food – we thought all curries are the same, but no, curry is nuanced! So our ignorance was exposed and we had to learn these things.”

But the team pressed on. “Love is taking care of people’s needs, not just paying lip service,” said Dr Mahadevan.

“The workers used to be almost invisible, people we would see at a construction site or by the road. Covid has taught Singaporeans so many things. I hope we never forget these lessons on really seeing the people in our midst and saying ‘thank-you’ to them.”

Fighting for the team

As soon as the dormitories were set up, Dr Mahadevan was whisked away to another Covid role: Setting up three community care facilities (CCF) at Tuas South, Chia Ping and Big Box.

“You weren’t just fighting for the patients, you were fighting for your teammates.”

The minutiae involved in converting an existing industrial building, flatted factory and shopping mall into hermetically sealed living quarters for almost 5,000 patients was mind-boggling.

As the first wave, Dr Mahadevan and the task force had to make sense of the situation. And fast.

Suddenly he found himself in a project manager role.

Everything from food to cleaning to removal of garbage had to be considered to make the facilities habitable. Infection protocols were numerous – even the cleaners had to be PPE certified.

An army of doctors was pressed into service. In the NUHS cluster, doctors hailed from hospitals such as NUH, Ng Teng Fong and Alexandra, together with volunteer healthcare professionals and private healthcare providers.

“They were the unspoken heroes in the whole story.”

“There were people laid off from the casino industry and Gardens by the Bay who were channelled to run the patient care – from the time they were dropped off in buses, to checking them in, to assigning rooms, to taking care of their food … it was like running a medical hotel.

“So many people were pulling together, from medical workers to interpreters, cleaners to dorm operators, contractors to service staff who had been retrained for these Covid times. The police officers and security personnel, too, faced a lot of struggles.

“They were the unspoken heroes in the whole story. Some who had lost their jobs came to work daily despite the high risks. Some were volunteers who were never celebrated nor thanked, but they gave their all anyway.

“When I saw everyone banding together, it really motivated me to keep going,” he said, clearly moved by the memory.

“That teamwork is what caused us all to go back and fight another day. You weren’t just fighting for the patients, you were fighting for your teammates.”

Being the Medical Lead at the NUHS CCFs meant taking on a project manager role, throwing Dr Mahadevan out of his comfort zone.

Despite his seniority as a clinician and a medical educator, he found himself a student again, learning new hard and soft skills.

“I was completely out of my comfort zone,” he said ruefully. “There were many times when I didn’t know the answer and I had to consult my infectious diseases colleagues. Sometimes they didn’t know the answer either!”

“When you are in a Covid facility, the air is thick with the virus. The whole environment is ‘Covid-ised’, so to speak.”

At the time, exactly how Covid was transmitted was still a mystery.

“We were dealing with high-rise buildings that accommodated six, seven floors of patients and staff who occupied the bottommost level. We had to ask ourselves questions like: Will the coronavirus filter down and affect people in the lower floors? So we had to do some circulatory studies.”

The demands of the role filtered down to his family life. His wife, Dr Sheila Vasoo, a rheumatologist in private practice, joined him as a volunteer with an NGO at one of the dormitories on weekends.

“I would be lying if I said there wasn’t any fear, but it’s a healthy fear that keeps us on our toes,” said Dr Mahadevan. “When you are in a Covid facility, the air is thick with the virus. The whole environment is ‘Covid-ised’, so to speak, and we had to be careful, even with our footwear.”

With the team at the Tuas South Community Care Facility.

He and his wife had been young frontliners during the SARS outbreak in 2003, when their sons were just toddlers. Dr Alexandre Chao, the vascular surgeon who died from SARS while serving in a hospital fighting the virus, had been Dr Mahadevan’s classmate in school.

“The boys said, ‘Yeah, don’t worry, Mum and Dad, if we get Covid, we get Covid.’”

That was the time the couple decided to “get our will sorted out”.

When Covid hit, they had a family consultation with their three sons. Two of their sons, Joshua, 21, and Joel, 20, are in medical school, while their youngest, Benjamin, 15, is in secondary school.

“We told our sons, ‘So Mum and Dad will be working among Covid patients, guys. We don’t want to isolate ourselves. Are you all okay with that?’ And they said, ‘Yeah, don’t worry, if we get Covid, we get Covid.’ So we had a family pact.”

By the end of 2020, the facilities were running smoothly and the task force handed over the project to a private healthcare operator. During the recent Covid spike, some CCFs were reactivated as Stepped-Up Community Care Facilities.

The power of faith

Caught, not taught, is how Dr Mahadevan describes the deep care that motivates him.

As a child, he had two great influencers – the family GP and his grandmother.

“Dr Wilmot showed me that the art of healing was seeing the whole person, not just about treating the illness.”

“When we were young, my dad used to take my sister and me to see Dr Wilmot Rasanayagam when we had coughs and colds. He was a Christian GP in the Selegie area,” he reminisced. “The clinic was always packed. My dad told me that many of the patients were poor and Dr Wilmot would see them for free.”

That made an impact on the young boy, who saw both suffering and kindness in the simple clinic. Dr Wilmot, who was also the Chairman of the Singapore Red Cross in the 1960s and 70s – became one of the reasons he would choose to become a doctor.

“Dr Wilmot showed me that the art of healing was seeing the whole person, not just about treating the illness.”

Another Godly influence came from his praying grandmother.

“After the Japanese Occupation, my grandfather died, leaving my grandmother poor and widowed at a very young age with five children,” he said.

The picture he has of his late maternal grandma is of her in her widow’s white sari, shawl draped over her head, praying for hours on her knees as she interceded, sometimes weeping, for those who were on her heart.

“My father went to church for my grandmother’s sake, but slept through all the sermons.”

“Even strangers from church would ask her to pray for them,” he remembered. “She would evangelise to the grandchildren and give us Ladybird books on Jesus to read.”

His late dad, a quiet, disciplined man in the police force, also spoke into his life.

“He was not a conversationalist,” said Dr Mahadevan. “But through his deeds and actions, you could tell he was a good man. After a bypass at 50, he was retired early at 55, something I think he struggled with because he still had a lot to contribute. But God had other ideas for him.

“My dad came from a traditional Indian family. He only converted to Christianity, at my grandmother’s insistence, to marry my mother.

“He went to church for my grandmother’s sake, but slept through all the sermons. I used to ask my grandma, ‘Why is he still hiding idols in the cupboard?’ And she would reply, ‘Pray, pray, pray for your dad.’

Dad Eric Mahadevan dedicated his life to Christ after his retirement from the police force. His quiet faith and genuine care for others impacted the young Malcolm deeply.

“Then one day in church – he never told us why – he actually listened to the message. And after that, there was no turning back. He smashed all his idols and truly gave his life over to Christ.

“So when he was forced to retire, he devoted his time to serving God. He would drive up to Malaysia on the weekends, go in to a Tamil church to preach and serve there.

“You know the question many of us have in our minds: What will my funeral be like? Who will come?

“When my dad died, the people who turned up for his funeral bore testimony to his life. Although he didn’t talk much, he always went out of his way for people and they could see his genuine care. So the Gospel was still being ‘preached’ at his funeral.”

Soft side of the house

Dr Mahadevan’s current job title is a mouthful: Designated Institutional Official (DIO), a role he officially took over in July 2020.

In essence, driving the training of the hospital cluster’s corps of residents in the NUHS Residency programme deeply answers the Associate Professor’s core values.

Some years ago, when he was one of the assistant deans in NUS, he met up with about a dozen medical students who were struggling.

“Singaporeans are very task-oriented. But the soft side of the house, the relational aspect, is critical.”

“At the time, there was a student who had ended his life, and everybody was very upset and wondered, ‘How come we couldn’t even tell?’

“I wanted to hear the students’ narrative – what were their struggle points, whether there were unintentional barriers to their reaching out for help,” he said. “When I asked, ‘How are you?’ I was surprised by how openly they shared their distress. Perhaps no-one had given them the space or opportunity for honest conversations.”

He ended up writing a thesis on stress in medical school, and found that 80% of his role in nurturing post-graduate students had to do with navigating relational problems.

“In tertiary education, we have this saying: Assessment drives behaviour. That means, for instance, if I set an exam and tell the students a particular component carries greater weight, they will naturally focus on that component. It drives behaviour.

“So, as leaders and organisations, what are we focusing on? Competency, character, calling? How are we driving our team’s behaviour?”

Looking back, the Emergency Medicine Senior Consultant believes God prepared him for his roles during this pandemic.

Relating a recent encounter with two med students, he said: “It was the last day of their attachment with me and at the end of the day I saw them peering into their computer. I asked what they were doing.

“The nurses asked me to come into the tearoom, sat me down, and gave me a warm cup of Milo and sandwiches.”

“They were following up on a patient – a 40+ year old man who had jumped down from the sixth storey. He was still barely alive, and they were pretty traumatised. It was the first time they had witnessed such a case and saw his chest being opened up in surgery. But nobody had really helped them process that.

“Singaporeans are very task-oriented. But the soft side of the house, the relational aspect, is critical for well-being and even getting the job done.”

In an interview for an NUHS video, the Senior Consultant shared a story that epitomises his idea of team ethic:

“When I was a houseman many years ago, there was one night when I was on call, and I was so busy, and suddenly I received a call to go to a ward … I ran there. And there the nurses asked me to come into the tearoom, sat me down, and gave me a warm cup of Milo and sandwiches.

“You know, this really almost brought me to tears … realising that there are team members who love one another, are kind to one another. And this helps us to do our work better. To look after the patients better.

“We know how we can teach knowledge and skills. But attitudes and values is something we have to role model.”

Living water

Ask if any of his pursuits is motivated by Scripture, he gives a quizzical smile. “All of it is.”

“In the Old Testament, the nation of Israel is given a clear mandate to care for the foreigners in their midst, the widows, the fatherless, people who could not care for themselves. (Deuteronomy 14:28-29, Leviticus 19:10, Psalm 146:9)

“This is something that was impressed in my heart early on,” he said.

“In this pandemic that’s dragged on for 22 months, it’s easy to have compassion fatigue.”

When he was a Medical Lead at the dormitories and CCFs, his chief consideration was: Primum non nocere. (Latin for “first, do no harm”.)

“My chief perspective was to look after the migrant workers, the Covid patients, the whole bunch of volunteers working at the facilities, including elderly cleaners. We didn’t want any harm to befall them.”

Looking back, he believes God had prepared him for the role. Even as a medical student and young doctor, he had been involved in medical mission trips to the Philippines and Cambodia. At NUS, he was the Associate Dean in charge of electives and would help link students up with needy communities.

While friends joked that he had jumped from the frying pan into the fire (so much for stepping into a “quieter” role), he was glad to be where the need was.

Dr Mahadevan with his wife, Dr Sheila Vasoo, a rheumatologist, with their sons, Joshua, Joel and Benjamin. Conversations around the family table inspired the two elder boys to also pursue medicine.

“One of the paradoxes of the Gospel that I try to wrap my head around is that the same God who tells us, ‘I came that they may have life and have it abundantly’ (John 10:10) tells us to daily pick up our cross and follow Him (Luke 9:23).

“This knocks at our paradigms of what an abundant life is. We think of abundant in terms of a big house and three cars, but even when we have that we may not have joy.

“I believe Jesus is saying that there will be many struggles in this world, but if we live it giving glory and thanks to God, our life will still be rich.”

How does he not get jaded and desensitised in the face of suffering and illness?

“In this pandemic that’s dragged on for 22 months, it’s easy to have compassion fatigue. This is when we find calibration from God and His Word, so we don’t become callous and jaded. All the attributes of compassion, grace, mercy – they come from God. If we tap on our own reservoir, we dry up quickly. But He is a stream of living water (John 4:10) and we just need to be the conduit for His peace and grace.”

“If we tap on our own reservoir, we dry up quickly. But He is a stream of living water (John 4:10).”

He has seen a lot of behaviour driven by fear.

“People come to the hospital with a lot of fear – fear of dying, of getting Covid, of vaccines, the migrant workers fear losing their income, the Government might fear that their policies will have the wrong outcome because they want to do the right thing.

“It has helped me understand what drives people who get angry because of fear, and to not scoff at or belittle them.

“The Bible talks about how we should fear God. (Isaiah 11:1-3, Deuteronomy 10:12). At the same time, we are told ‘perfect love casts out fear’ (1 John 4:18). This used to puzzle me … fear or don’t fear?

“I’ve come to realise that there is a good fear and a bad fear: Good fear draws us to God, while bad fear drives us from him.”

Where is God is in the pandemic?

“He’s exactly where He’s been since the beginning of time … on His throne.

“There are no surprises for Him. He has provided answers for us. In a sense, we fear the smaller things when we don’t fear the largest thing we ought to fear: God.

“When I am old and maybe demented and can’t remember anything, I just hope that the one word I have in my brain and on my lips is ‘Jesus’.”

RELATED STORIES:

“We were meant to be here”: SARS doctor who arrived in Singapore just before the outbreak

“There was no big blueprint, just the fingerprint of God”: HealthServe’s Dr Goh Wei Leong

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light