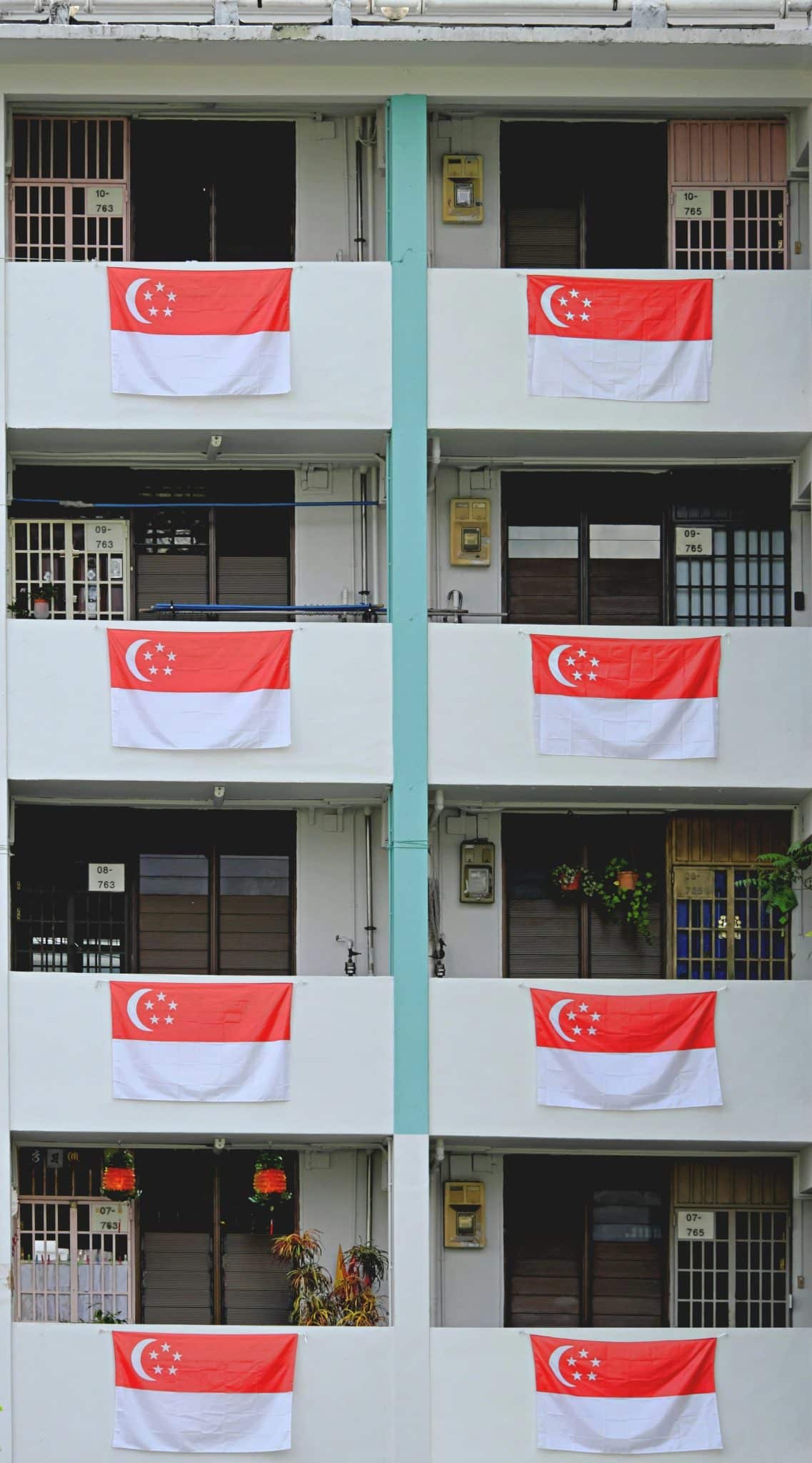

The latest slate of restrictions is aimed at reducing the pressure on our healthcare system. Photo by Amir Arabshahi on Unsplash.

These days “reprieve”, though a word, is a number – like “917”, which was the tally of new Covid-19 infections on the one day (Sept 21) last week when the current surge dipped to three digits.

That seems to have been an anomaly. The four-digit figure is now the norm, going by the updates of the last 10 days, and a peak of 3,200 new infections by next week is highly plausible, Health Minister Ong Ye Kung has said.

The hope is that a stable trough will come sooner rather than later, and that daily Covid deaths will no longer be just a matter of fact.

At press time the toll was 78, with the victims so far identified only by gender, age and comorbities, along with their vaccination status.

That number is about to change.

Someone I know just died of Covid.

“My mum passed away around 8-plus this evening,” the first text said. “We are all in shock. Coroner’s case.”

When the odds are stacked

The odds were already stacked against her when she tested positive. She was in her nineties and had the attendant old-age issues plus dementia, putting her squarely in the “vulnerable to severe illnesses” category.

Her main caregiver had tested positive, and the Ministry of Health (MOH) sent someone in full PPE gear to her home to swab her too. It was a foregone conclusion that she would be infected, and that an ambulance would be despatched to take her to the hospital.

“Last night they arranged for us to see mum’s body via video. Very sad. Wrapped in two big plastic bags.”

Four days later she was doing well enough to have an exit PCR test administered. If the result came back negative, she was to be discharged.

Sometime that night, however, the nurse on duty realised the blood pressure monitor was not registering a reading. Her body was cold.

Sudden death in a Covid-positive elderly person is not alarming, the attending doctor said. But because her passing had no specific cause at the point of death, further investigation was mandated by law.

Hence, the “coroner’s case” classification. A specialist doctor would be called upon to look over the medical history and certify no foul play. If necessary, an autopsy would be done.

In the meantime, standard protocol was in place. The morning after’s update: “Last night they arranged for us to see mum’s body via video. Very sad. Wrapped in two big plastic bags.”

The next text: “A police officer returned mum’s belongings, said we better trash it. She asked us to take out the dentures from the bag. I had to cut the bag and seal it back.”

Last days

I didn’t think I would feel so sad, but I did.

To me she was a person with a name and a face, of tender flesh and blood – with loving bonds to a closely-knit family, a soul behind what’s now a statistic.

The finality of it all seemed harsher than it needed to be.

Looking on as she was being stretchered into the ambulance, the family’s fear of losing her was palpable.

She was a person with a name and a face, a soul behind what’s now a statistic.

Nonetheless, little did they realise that this was to be their last chance to see her, let alone say goodbye. Besides their respective Quarantine Orders and personal decisions to self-isolate, there was also the no-visitors-to-hospital-wards rule.

The pace at which events then unfolded proved bewildering. All too quickly, they were to find out that Covid-positive deceased go from the morgue to the crematorium as soon as a funeral could be arranged, with coffins sealed. There was no wake to be had.

It reminded me of the passing of a relative of mine during the Circuit Breaker last year. The cause was not Covid but cancer. While the death was not unexpected, there still was a similar quality of it all being eerily surreal.

She died one Saturday evening, was embalmed that night, and cremated at Mandai the next afternoon. Wrapping it up in less than 24 hours was our way of circumventing the tight restrictions at the time.

Only 10 were allowed in a funeral then; the limit is now 30.

Because of the physical distance, you felt like you were crying alone behind your mask.

Just to drive in through the Crematorium’s imposing gate, we had to show official passes – one pass per person. In the service hall, it was two persons per row, everyone seated alternately, one metre apart.

Her pastor gave a short message of hope, then we walked to the coffin to pay our last respects in single file. The undertaker had prepared individual white roses for us to put therein – a small token of beauty in the face of a desolate circumstance.

Because of the physical distance, you felt like you were crying alone behind your mask. You could not hug anyone. You were not even supposed to be near anyone.

In the viewing gallery, it was also only two persons per row – that was as much as safe distancing permitted. We watched the coffin roll into distant memory. After it was gone from sight, we made our way down a flight of steps, washed our hands, paid the undertaker, and left.

There was no socialising. Was there anything to say anyway?

The upper hand

One thing.

“Whoever believes in Me, though he die, yet shall he live.” – John 11:25

After almost two years, the Covid-19 pandemic’s scourge may seem as relentless as ever, leaving us with fewer choices about the way we live and even fewer about the way we die.

Yesterday (Sept 27), to minimise the strain on our hospitals, a new slate of restrictions kicked in. Whether we have grief to share or gripes to vent, it really only matters that life’s everlasting words have already been said: “Whoever believes in Me, though he die, yet shall he live.” (John 11:25)

There remains yet a response to be made about the reality that Christ died for our sins, was buried, and on the third day rose again (1 Corinthians 15:3-4), defeating death and paving the way for sinful man to be reconciled to holy God: “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised Him from the dead, you will be saved.” (Romans 10:9)

My hope is that you would take some time to consider the length and breadth of your days, the height and width of your concerns.

The New Living Translation puts it this way: “Teach us to realise the brevity of life, so that we may grow in wisdom.” (Psalm 90:12)

The truth is, the Father’s commandment is eternal life (John 12:50). The choice where you spend it is yours.

RELATED STORIES:

“It was a miracle”: Dr Cynthia Goh on the chain of goodness that led Bangladeshi worker home

Let there be the vital signs of life, even with our first COVID-19 deaths

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light