Out of the wartime darkness of Changi Prison, generations of S’pore church leaders were birthed

This National Day, Salt&Light looks at remarkable landmarks in our nation where faith sparked and grew under extraordinary circumstances, impacting the Singapore Church and beyond.

by Gracia Lee // August 8, 2022, 2:23 pm

Prisoners of war attending a church service in a small chapel in Changi Gaol. Photo courtesy of the Australian War Memorial (117658).

Did you know that there was a time in the Singapore Church’s history when it did not have local church leaders?

Up until the early 1940s, the local Church was served mainly by foreign European missionaries. While many of these ministers recognised the need for indigenous leaders, training up a local pool had proven to be a challenging task.

But it was at an unlikely time, and in an unlikely place, that God decided to move.

When Singapore fell to the Japanese during World War II, many of these European clergymen were rounded up and packed off to prisons throughout the island as prisoners of war (POWs), leaving behind their congregations.

It was a dark time for the nation, but within the confines of these prison walls the first sparks of unity between church leaders of various denominations were being ignited, paving the way for generations of local leaders to be raised up through the region’s first union (inter-denominational) theological college.

A spiritual revival within prison walls

Despite the curtailment of freedom for the POWs, they were allowed by the Japanese to carry out religious activities within the camp – which many did with great fervour.

“In the grossly over-crowded camps building material was scarce and many of the churches seemed to grow out of nothing.”

“In adversity men turn to religion for moral support,” wrote Major-General AE Percival in the introduction of The Churches of the Captivity in Malaya.

“The officers and men who fell into Japanese hands at Singapore in February 1942 … were no exception to this rule.”

Published shortly after the war was over, the book documents the makeshift churches, built and attended by prisoners of war, that had sprung up in the prison camps.

Written and compiled by Rev JN Lewis Bryan, it records eight such churches in Changi, including St George’s Church, of which the Changi Chapel was modelled after.

An altar in a chapel that was built by Australian prisoners of war. Photo courtesy of Australian War Memorial (043172).

Major-General Percival recounted: “In the grossly over-crowded camps building material was scarce and many of the churches seemed, as it were, to grow out of nothing …

“Every Sunday the churches were filled, and, where there were no churches and no chaplains, services were held in ordinary buildings or in the open air and were conducted by the prisoners themselves.”

A packed church service in Changi Chapel. The chapel was shipped to Australia in 1947 to be a memorial for the POWs. A replica of the chapel was built and now sits at Changi Chapel & Museum. Photo courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

At the Changi camp, there were Sunday and weekday services, confirmation classes and ceremonies, choir practices and daily celebrations of Holy Communion, even if it had to be taken from under the bars of the prison cage.

There were daily celebrations of Holy Communion, even if it had to be taken from under the bars of the prison cage.

For bread, they used rice flour, maize flour or tapioca, depending on what was available.

For wine, they boiled blackcurrant jam or raisins, and even gula melaka, served in pewter mugs that had been bought from Thieves’ Market at Rochor Canal and smuggled into the prison.

Rev Dr Andrew Peh, a lecturer at Trinity Theological College (TTC) whose research interests include colonial missions history of Southeast Asia (Singapore), told Salt&Light that there are records of POWs, many of whom were nominal Christians, finding their faith renewed in prison.

“Because of the ability to just gather for prayer, for chapel services on Sunday, they were then exposed to what it meant to live out the faith that was taught to them when they were younger,” he said.

Every block under the care of a priest

With this spiritual fervour also came an unprecedented unity among clergy of denominations who, up until that point, had been operating more or less independently.

“At Changi, faced with uncertainty and the constant threat of death, the POWs were stripped not only of their freedom, but also of the bounds of denominational divisions,” details At The Cross: The History of Trinity Theological College (1948–2005).

“With limited resources and space, and the unquestioned need to depend on each other for survival, it became instantly clear from the first days of their incarceration that interdenominational differences had to be put aside.”

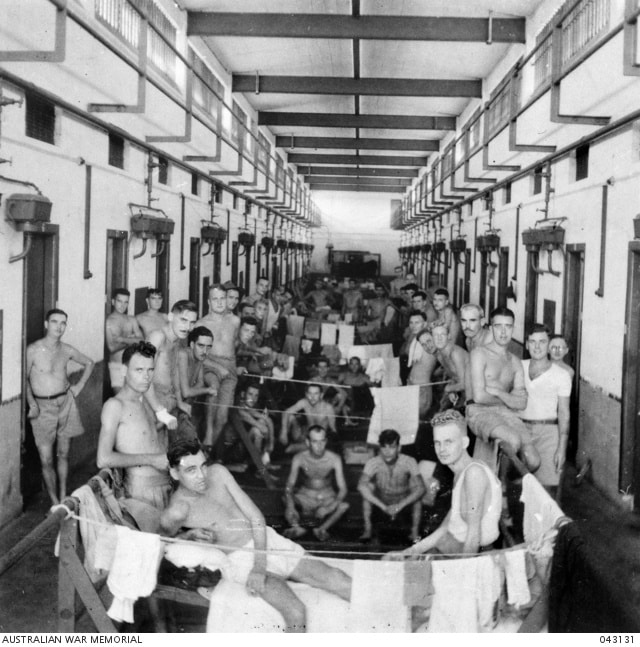

Australian prisoners of war in the Changi Gaol. Photo courtesy of Australian War Memorial (043131).

The various denominations started having combined church services that were held regularly throughout the Occupation years. They also began to think about what it meant to serve God together, especially during a time of war.

With nine Anglican clergymen, three Methodists, two Presbyterians, one Brethren and 14 Salvation Army officers interned at Changi Prison, it became possible for every block in the prison to be under the special care of a priest.

“The various denominations … began to think about what it meant to serve God together, especially during a time of war.”

In his book Priest in Prison, a firsthand account of living in Japanese-occupied Singapore, Rev John Hayter wrote: “We all got on with one another extremely well. This feeling of close fellowship between the non-Roman clergy made many aware of the need for Christian reunion.

“It was difficult to avoid being conscious of our divisions and being ashamed of them, when we were living and working at such close quarters … The loyalties of each individual to his own Church were fully recognised, but we found ourselves going further than that. There appeared a sense of shared Christian loyalty which rose above narrower divisions.”

Rev Hayter also recounted how a group of clergy and laity, called the Friends of Reunion, would meet every week in the prison to exchange views on Christian doctrine and living, as well as to have robust discussions on their differing opinions.

“For a time, as was to be expected, it was the differences between us which became most prominent and the exchanges sometimes tended to become almost heated.

“However, once that stage was passed, we began to discover the things about each other which we had in common and we found a new and greater understanding of one another,” wrote Rev Hayter.

Training up local leaders

This experience, along with the personal friendships that were formed, led these ministers to think of ways to work together after the war was over.

In the Trinity Theological College Annual (1964–1969), Rev Robert Greer, a Presbyterian minister who was among those interned at Changi, wrote: “We felt it would be quite wrong to return to insulated denominational establishments from where we would wave to each other from a distance but would in actual fact have little contact.”

“We began to discover the things about each other which we had in common.”

In particular, they felt it was time to unite their resources and together staff a theological college which would raise up local indigenous leadership to serve the needs of the Church.

Up until that point, the local Church had relied on European missionaries to run its ministry. For the most part, Asians were only trained to become assistants to these missionaries.

Due to the challenges posed by a multiethnic and multilingual society, however, the foreign missionaries began to see the need for a pool of trained local clergy who could preach and minister effectively to the locals in the local languages and dialects.

Raising up local clergy would also reduce the over-reliance of the local Church on foreign missionaries for its growth and permanence, an issue that became more apparent during the war after most of the church leaders were interned.

But the establishment of such training facilities had proved to be challenging.

Prior to the war, the Methodists had set up two training schools: The Jean Hamilton Training School in 1898 and the Eveland Training School in 1902. Both faced several obstacles, such as a lack of funding, resources, native helpers and quality applicants.

“The majority of the clergy had been recruited from outside Malaya … Henceforth, we would train our own people.”

Not only were the students of varying abilities, “there was also a multitude of languages with which the school had no resources to cope, be it teachers or books”, details At the Crossroads: The History of Trinity Theological College (1948–2005).

To consolidate resources, both schools merged in May 1940 to become the Malaya Methodist Theological College (MMTC).

When the Japanese invaded in 1942, the students and staff were scattered. The principal of MMTC, Rev Hobart B Amstutz, was among those interned in Changi.

Yet it was within the confines of these prison walls that Rev Amstutz found a solidarity with ministers of other denominations, who vowed to establish together a union theological institution that would eventually become Trinity Theological College (TTC).

In the Trinity Theological Annual (1964–1969), Rev Greer writes: “We do not forget the work that had been done in this direction by the Methodists before the war, but the new College was to be a much more ambitious project.

“Hitherto the majority of the clergy had been recruited from outside Malaya to serve in the Malayan Church. Henceforth, we would train our own people.”

Passing on the spirit of unity

In October 1948, three years after Singapore regained its freedom from the Japanese Occupation, the ministers made good on their promise to form a union theological college in Singapore.

“The story of Changi Prison reminds us that the road to the mountaintop often necessitates passing through the valleys.”

Trinity Theological College – a joint venture among the English Presbytery, the Anglican Church and the Methodist Church – welcomed its first students. It would later be joined by the Lutherans in 1963.

The establishment of the College was a significant milestone for the local Church. No longer would it need to rely on foreigners. No longer would it need to send people overseas to be trained. A new generation of local leaders could be raised up right here on Singapore soil.

With the school motto being Lux Mundi, Latin for “light of the world”, the founding principals also set their eyes on a greater vision.

“The intention was that Singapore would be that centre in which local pastors and leaders in various Southeast Asian countries could be trained and could assume leadership in those other countries, so that indeed the light of Christ would penetrate all the different countries in Southeast Asia,” said Rev Dr Peh from TTC.

“We may all have a different heritage and distinctive, yet we are all one in Christ.”

More than seven decades on, this has become a reality. International students today make up almost 40% of the student population, hailing from more than 10 countries including China, Indonesia, Vietnam and even Japan, where only 1% of the population is Christian.

Locally, cohorts of pastors and church workers have passed through TTC’s classrooms before being sent out to lead, guide and run the 600 churches here.

While these graduates come in with their own denominational backgrounds, they leave with a better understanding and appreciation of others’, passing on the same spirit of unity that undergirds the school’s history.

“In our teaching of theology, our teaching of church history, we will give equal weightage to different denominations. Even in our classes in theology, there is an emphasis on helping students understand what would be an Anglican distinctive, what would be a Presbyterian distinctive, or what a Lutheran distinctive would be, so that they are not without an understanding of what another brother or sister from another so-called denominational tradition would hold on to,” said Rev Dr Peh.

Celebrating its 74th anniversary this year, Trinity Theological College is now home to almost 40% international students from more than 10 countries. Photo by Thiam Kwee from TTC’s Facebook page.

“In many ways I think Trinity Theological College is a microcosm of this ecumenical movement within the Church, for which Jesus would have prayed for in John 17 – that they may be one,” he added. “We may all be different, we may all come from different backgrounds, we may all have a different heritage and distinctive, yet we are all one in Christ.”

Suffering precedes victory

This National Day, the story of Changi Prison reminds us that the road to the mountaintop often necessitates passing through the valleys, said Rev Dr Peh.

TTC staff and students attending chapel service. Photo from TTC’s Facebook page.

In a prosperous society like Singapore, it is easy for the Church to be preoccupied with success and victory as we yearn to advance God’s Kingdom.

“When we are united, we are able to collectively share the important message of being a disciple of Jesus.”

However, we must have a right perspective of the way God sometimes chooses to work.

Looking to Holy Week as an example, where the passion and suffering of Christ preceded His resurrection, Rev Dr Peh said: “It is through suffering that God will show His purposes for the Church.”

And as we thank God for this gift of unity within the Church in Singapore, let us hold on tightly to it even when it may be challenging to do so.

Said Rev Dr Peh: “God’s Kingdom is larger than the Methodist Church. God’s Kingdom is larger than the Anglican Diocese or the Presbyterian Synod. When we are united, then we are able to collectively share the important message of being a disciple of Jesus.”

MORE STORIES ON SINGAPORE’S FAITH LANDMARKS:

St Andrew’s Cathedral: Landmark of love and sacrifice during the darkest days of WWII Singapore

St Andrew’s Cathedral: Landmark of love and sacrifice during the darkest days of WWII Singapore

70-year-old Trinity Theological College birthed in a dark period of Singapore’s history

A Bicentennial look-back at the extraordinary history of the Singapore Church

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light