Her son took his own life, she would not let others do the same

by Christine Leow // October 29, 2021, 12:18 pm

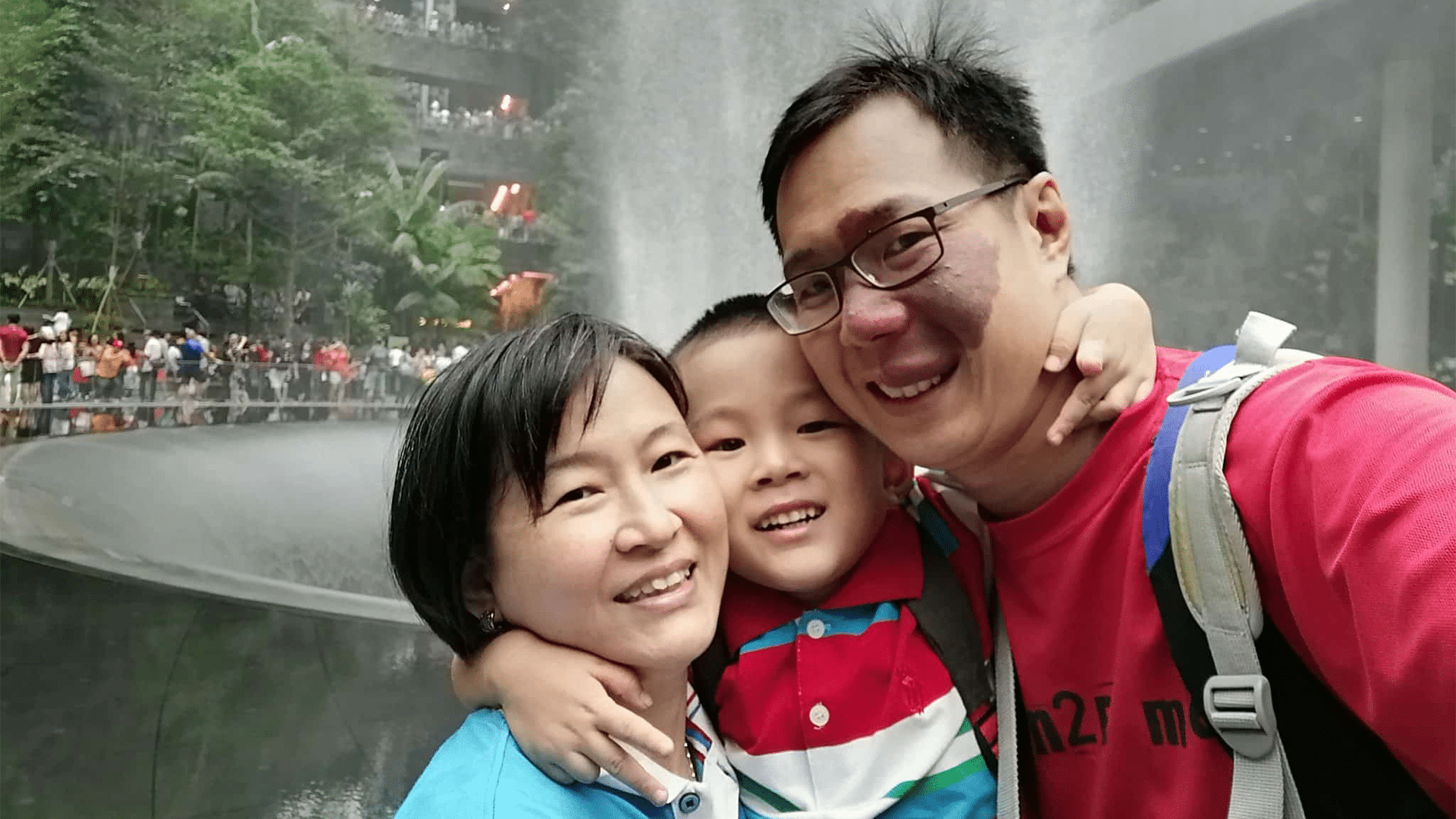

Zen Dylan Koh and his mother Elaine Lek in Melbourne in 2018. He was in Melbourne to finish his junior college education; Elaine visited him often. All photos courtesy of Elaine Lek.

Trigger warning: This story contains material about the suicide of a minor that some may find distressing.

Every morning when Elaine Lek wakes up, she places her hands on top of a pair of handprints belonging to her son, Zen Dylan Koh. This small gesture is her way of feeling connected to her firstborn.

Three years ago, just a month shy of his 18th birthday, Zen took his own life. He had been depressed.

Zen’s handprints and a lock of his hair were presented to the Kohs by DonateLife Melbourne after the family donated his organs.

“Losing my child to suicide caused me such immense pain as a mother,” said Elaine, 56.

“I could see tears rolling down his eyes. That night, he was brain dead.”

His passing was all the more gut-wrenching because the paramedics had managed to revive Zen after his suicide attempt.

For three days as he laid in the intensive care unit in Melbourne where he had gone to further his studies, Elaine and her husband Koh Say Kiong clung to the hope that their child would recover.

Said Elaine: “For three days and three nights, I cuddled him while he had non-stop seizures.”

Then, the doctors broke the news to them.

“They told me that even if he did pull through, he would never be the same. I couldn’t be selfish to ask him to fight. He was such an active boy. I had to let him go.

Zen on holiday in Aspen, Colorado, at 15. He was very sporty. Apart from horse-riding, he played golf, hockey and football. He could also ski, water-ski, roller-blade, dive and picked up skateboarding in Melbourne.

“I told him, ‘Son, thank you so much for choosing me as your mummy for 17 years and 11 months. Go and find your happiness and your eternal home.’

“I could see tears rolling down his eyes. That night, he was brain dead.”

A hidden pain

Zen had come along late in Elaine’s life.

She had been busy with her career, first as a buyer for major department stores, then working at Luzerne, a tableware company started by her late grandfather. She is now its Chief Operating Officer and Head of the Global Brand Team.

She was in her mid-30s when Zen was born after a “not-so-easy” pregnancy.

Having Zen changed Elaine’s mind about motherhood.

Loving, lovable and intelligent, Zen was a light in his parents’ lives.

“He was a very easy child. Lovable, loving, intelligent – really a blessing. Because of him, I was in love with motherhood. He made me enjoy being a mother.”

That was why Elaine and her husband were eager to have another child. Two years after Zen was born, they welcomed their second son Max into the family.

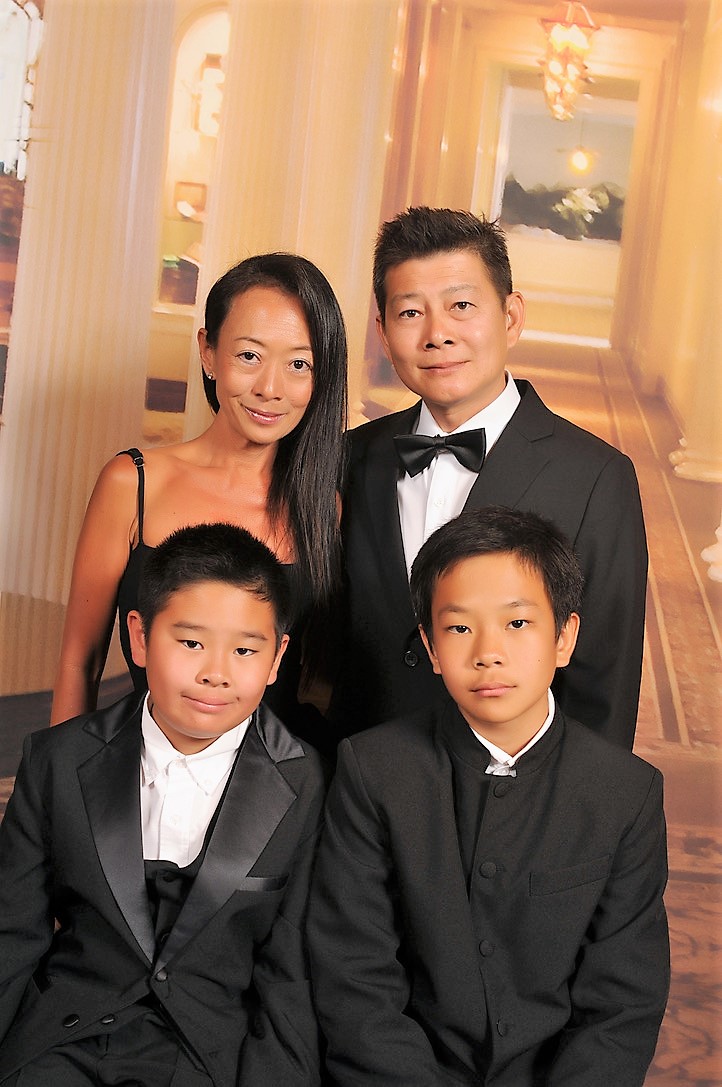

The Kohs with their sons, Max (left) and Zen (right), on a Mediterranean cruise.

Sporty and outgoing, Elaine and Zen shared many interests and were very much alike.

Fashionable, sporty and popular, Zen and Elaine shared much in common.

“Because of him, I was in love with motherhood.”

“They always say that sons will never share with their mothers as much as daughters. But Zen was different.

“He also knows that I am not the kind who is judgemental. I always told him, ‘I am your mum but I am also your friend.’”

But the boy with a “goofy sense of humour who wouldn’t hesitate to make his friends laugh” lived under a cloud of darkness.

Elaine would find out at Zen’s wake that this ran in her family. Many of his cousins and her relatives across generations shared with her that they, too, battled depression.

“So, in Zen’s case, there was a genetic predisposition. It’s a myth that only those from dysfunctional families suffer from depression.

“Zen lived a blessed life and was really loved by everyone. He had everything and yet we lost him. Depression does not discriminate.”

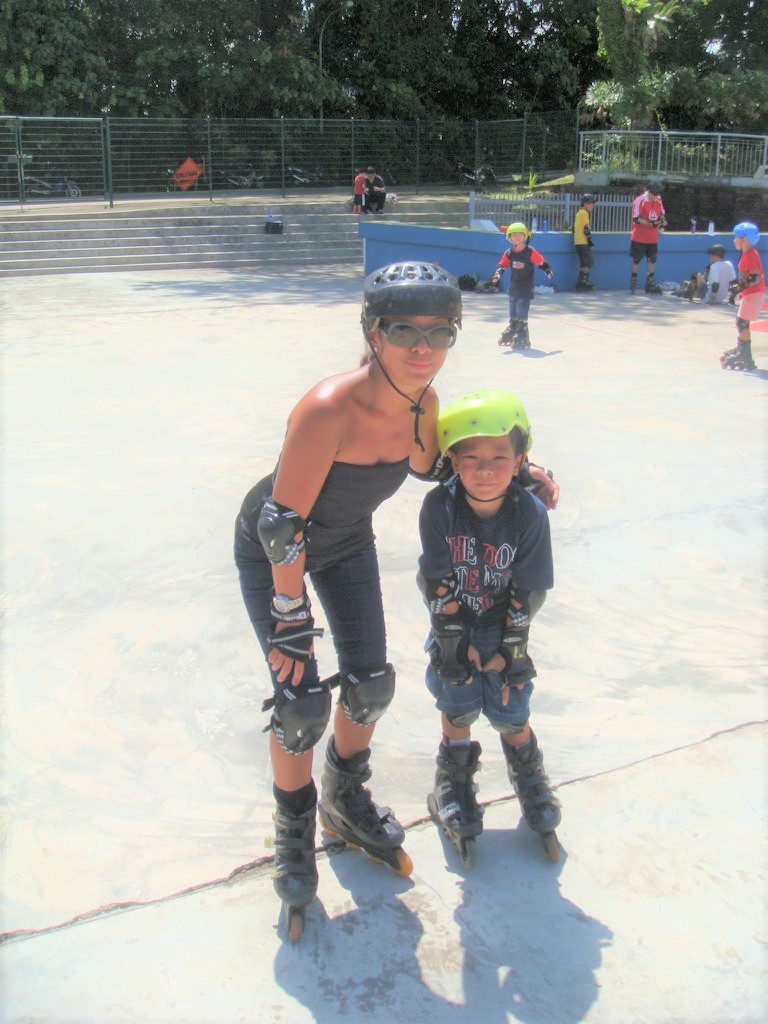

Zen diving with his brother and mother. He was an advanced diver.

When Zen went to junior college, Elaine and her husband started to notice a change in their usually upbeat son.

“He was having a lot of anxiety. He would skip classes because they made him anxious.”

Zen (right) in junior college. He was popular and seemed happy in the beginning.

Then, Zen experienced relationship problems that caused him to become withdrawn and resort to self-harm.

Elaine sought professional help and the psychiatrist diagnosed him with Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD) and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). For a while, Zen took medication for the ADD. But he stopped because, while the medicine helped his concentration, it exacerbated his anxiety.

To give him get a fresh start and alleviate academic stress, Elaine sent Zen to Australia to finish his junior college education.

Zen (bottom right) with his friends in Melbourne. In his hands is his favourite skateboard. He picked up skateboarding while in Australia and that was how he got about in the city when he studied there.

At first, he appeared to thrive. But, by the second term, the anxiety re-surfaced and he was self-harming again and talking about suicide.

Elaine believes that playing counsellor and confidante to his friends who were also struggling with mental health issues “dragged him down”.

(Left to right) Elaine enjoying ice-cream with Zen and his best friend in Melbourne. She visited him often when he was studying there.

When Zen came home for the holidays, Elaine took him to another psychiatrist who confirmed that he had GAD as well as mild depression. Zen was prescribed anti-depressants. But he would return to Melbourne worse off than before.

“He had everything and yet we lost him. Depression does not discriminate.”

“Within less than two weeks, he became very erratic. He went on an online shopping spree and wiped out his bank account. He refused to take my calls or answer my WhatsApp messages.

“He became withdrawn and refused to go for classes. And he started banging his head on the wall and caused a big crack.

“One day, he bought a rope from a hardware store and demonstrated to his friends how to tie a noose.”

That was when his friends called Elaine and she flew to Melbourne to help him. They had dinner. He confided in his mother that he had seen a school counsellor and even agreed to go for professional therapy with a psychiatrist.

But that night, Zen attempted suicide.

This was the last picture taken of Zen. A few hours after dinner with Elaine, he took his own life.

“At 1.30am, I received a call from his house mates. My hotel was a five-minute walk from his house. I ran there. It felt like the longest run of my life,” said Elaine.

Three days later, Zen passed away.

It was only after he had killed himself that Elaine discovered that anti-depressants could cause increased suicide ideation in a small percentage of youths in the first few weeks of use.

“The psychiatrist didn’t warn us. The pills were packed in clear plastic. There were no contraindications.”

Not in vain

After Zen was declared brain dead, Elaine and her husband decided to donate his organs.

“We wanted to focus on saving lives.”

“I just could not let Zen’s death be in vain. Somehow, some good had to come out of it,” she said.

Six people would receive her son’s organs – heart, lungs, liver, pancreas and kidneys.

“I always tell myself, while Zen took his life, he gave six lives back.”

But husband and wife wanted to do more.

Three months after they lost Zen, they started The Zen Dylan Koh Fund. The fund supports youths with mental health issues in need of therapy by paying for their professional counselling.

Zen (bottom, right) was popular and well-liked, often displaying his goofy side with his friends. He was also a steadfast friend, often providing a listening ear and comfort to others.

Those under the age of 25 who do not have the means, those who do not want their parents to know about their struggles, or those whose parents are not supportive of their efforts to get help can turn to the fund.

“We wanted to focus on saving lives. The fund focuses on high-risk youths, those who have suicidal thoughts or behaviour, including self-harm.”

“He wanted to help others like him because he thought he would be able to understand them.”

They also wanted to spare other youths the pain that Zen had suffered. After his passing, Elaine had found a heart-breaking text message on his handphone that he had sent to a friend.

“He wrote, ‘I am born to be sad. I can never be happy for more than a week at a time. If I can take away the sadness from everyone around me, I would because I cannot be any more sad.’”

Elaine would also find out from his text messages that Zen had planned on studying Psychology.

“He wanted to help others like him because he thought he would be able to understand them.

“It gave my husband and me the idea that maybe we can help Zen fulfil his last wish to help others.”

Since the fund was started in 2019 with the S$100,000 the Kohs had raised, more than 30 youths have benefitted from it, including 10 who were added to the list this year. Of these, 10 have since managed so well that they no longer require therapy.

Hope beyond this life

Even as Elaine tried to make meaning of Zen’s death, there was one question that troubled her: Where was Zen now?

Raised in another religion and educated in a Catholic school, she had always known that there was a God. She was less certain about the afterlife.

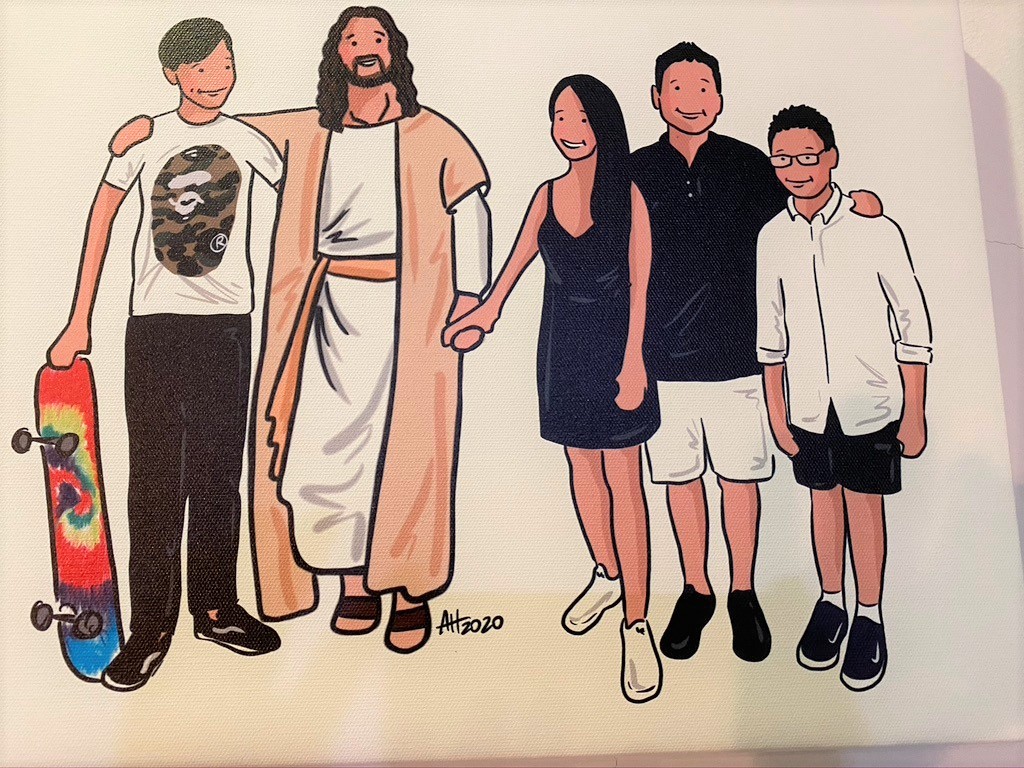

A family portrait that would inspire Zen’s friend to create a piece of art.

When she asked those who had come to perform the non-Christian last rites for her son in Singapore about the afterlife, she was told that she had to perform various tasks to earn merits for Zen to be reborn. But there was no answer as to where he had gone after death.

“The best thing about being a Christian is the hope.”

Google searches about the afterlife threw up different opinions.

“There cannot be so many different heavens for different people,” said Elaine.

Then, a friend took her to church.

“When I entered the church, there was this feeling of calm. Hearing about a loving, compassionate God made me full of hope.”

But what brought Elaine the greatest comfort was the three-hour conversation she had with the Catholic priest afterwards. He taught her about God and answered her questions about life after death.

This artwork presented to the Kohs by Zen’s friend was particularly meaningful to Elaine who yearned to know where her son was after death.

Zen had gone to a mission school and, clearing his room, Elaine had found his Bible with verses that he had highlighted.

“Every morning that I wake up, I am one day closer to seeing my son again.”

“I was assured that Zen was in heaven. Talking to the priest, he was able to tell me what no one else could.”

Drawn by the compassion of God and the hope that there was life everlasting for those who believed in Jesus, Elaine decided to turn to God. She spent a year going for classes to learn more about the faith and was baptised in 2020.

“The best thing about being a Christian is the hope. I know I have hope. I am so sure that when I die, it is not the end.

“I will see Zen again. In the meantime, he is not in pain. He is having a blast with Jesus. That gives me a lot of comfort.”

Zen and Elaine in Nepal in March 2017. They had gone there to do volunteer work with a doctor.

Her faith has also given her a new way to view a life bereft of her elder son.

“Every morning that I wake up, I am one day closer to seeing my son again rather than one day further away from having him here with me.”

Remembering Zen

Meanwhile, Zen is still very much a part of Elaine’s life.

“I often host the mothers who have also lost their children. With them, we can talk about our children and no one would think we were bonkers.”

Her advocacy work is her way of remembering him. She is part of the PleaseStay Movement, an advocacy group calling for the prevention of suicides among young people.

She regularly gives talks about suicide prevention and also joins support groups for parents who have lost their children to suicide.

“I often host the mothers who have also lost their children. With them, we can talk about our children and no one would think we were bonkers.

“We have journeyed together for three years. When we get together, we don’t cry anymore. We are now able to talk and laugh. All that laughter helps.”

Every evening, Elaine and her husband light a candle on the balcony to remember Zen, and they sit there talking about him.

“They are my way of keeping Zen close.”

Elaine also literally carries the memory of Zen with her wherever she goes. A month after his death, she got two tattoos. One is an infinity sign with her son’s name on one side and the word “mummy” on the other on her left wrist.

“It symbolises my bond with Zen that can never be broken.

“In the early days of losing him, when I walk, I would put my right hand over my left wrist and it would feel like he was guiding me.”

The tattoo on her right wrist says “We part only to meet again”.

To mark the second year of his passing, Elaine tattooed the design of Zen’s favourite skateboard on her arm.

This year, she added two more tattoos.

Added this year to commemorate the third year of Zen’s passing, this tattoo is a reminder that though her son is gone, Elaine is not alone. Jesus walks with her.

These are different. They not only remind her of Zen, they also remind her of the hope God has given her despite her loss.

“It’s my way of keeping Zen close.”

RELATED STORIES:

“To live is Christ, to die is gain”: A full-time church worker’s struggle with suicide

He tried to run away, but God taught this ultra-marathoner to run from depression instead

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light