Talk through the heart wounds, it’s the first step to healing: Salt&Light Family Night panellists on helping children through trauma

by Christine Leow // September 2, 2021, 10:42 am

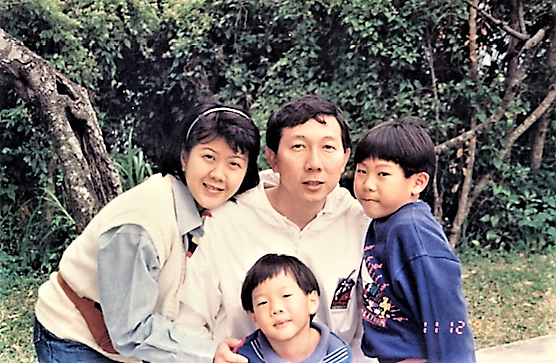

When her husband died after battling two rounds of cancer, Joan Swee was left to help her young sons, then aged six and eight, through the trauma. Photo courtesy of Joan Swee.

When Joan Swee lost her husband of close to 12 years to cancer, she was left with two grieving sons who were just six and eight.

“My children were very badly affected,” she recalled.

“In my desperation, I really cried to God.”

But she had no clue how to help them.

Too young to be able to express their grief, they reacted in the only way they knew how.

“There was a lot of acting out, hitting each other,” said Joan. “There was so much anger. They were angry with God.”

She had few resources at hand. This was 1994, well before the days of the Internet and Google searches.

“I saw my sons being so disturbed but I didn’t know what to do. I was grieving myself.

“In my desperation, I really cried to God and God heard my desperate cry.”

As Joan sought out books for help, she came across one that seemed to have been written just for her sons.

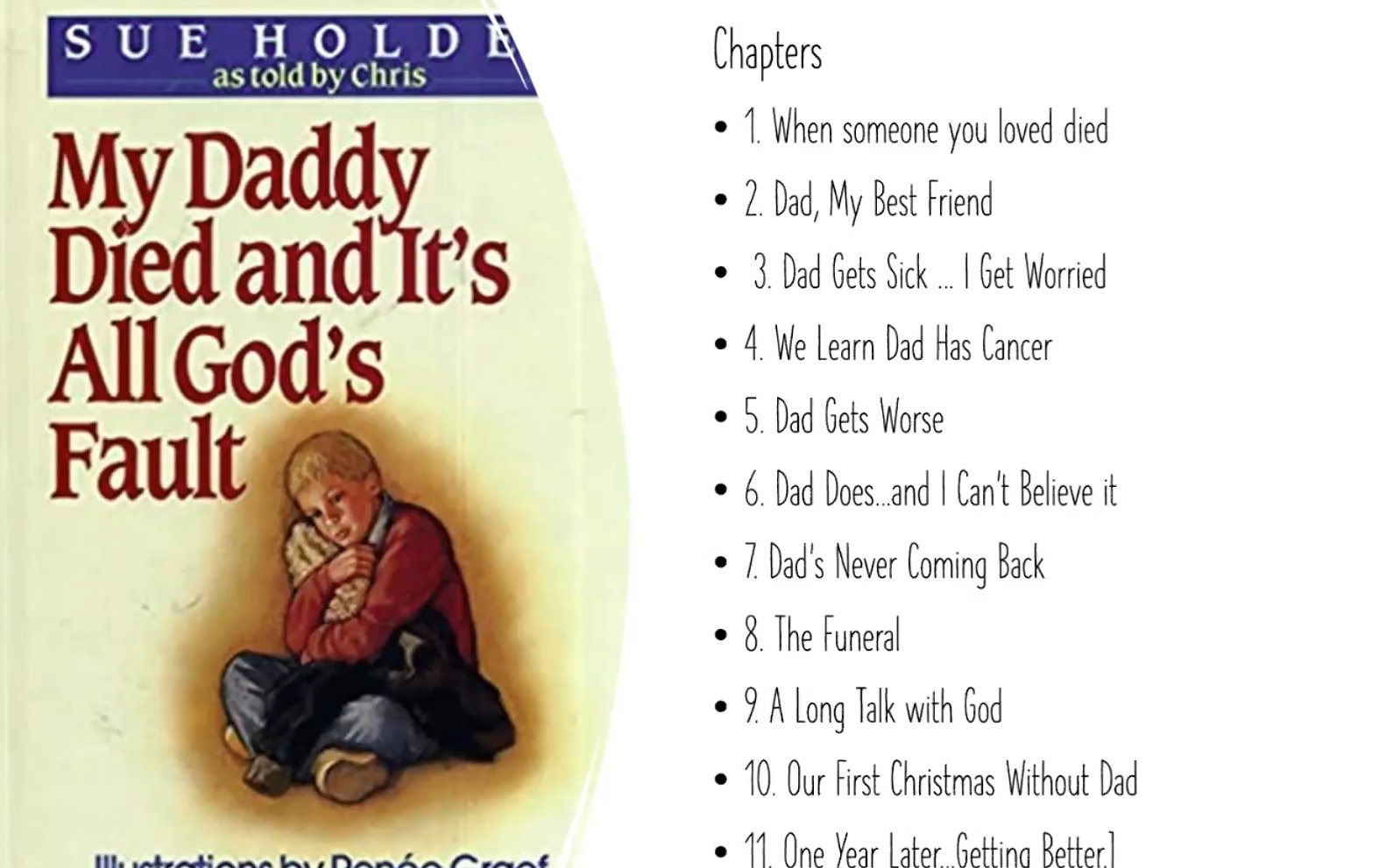

Called My Daddy Died and It’s All God’s Fault, it was written by Sue Holden through the eyes of a nine-year-old boy whose father passed away from an illness.

This book helped Joan to talk to her children about their grief over losing their father. Screengrab from Salt&Light Family Night.

“I read the whole book first. Then, chapter by chapter I read and dialogued with my boys, asking them what they thought about what was written, what they were thinking, how they were feeling about what had happened.

“I literally used the book to process their grief with them.”

As Joan sought out books for help, she came across one that seemed to have been written just for her sons.

Joan shared this on Salt&Light Family Night (August 31) as the chat show discussed how to talk to children about traumatic events. Nearly 200 viewers came on the Zoom chat, where about 1 in 3 had children or knew someone in their lives who had experienced trauma.

Since that first attempt at talking to her children about their trauma, Joan has walked with countless widows and their children as co-founder of Singapore’s only widow support group, Wicare.

Now a counsellor and grief recovery specialist, she is also the founder of Whispering Hope Singapore, a consultancy that helps people manage their losses.

On the Salt&Light Family Night panel with Joan were Senior Consultant Psychiatrist at Adam Road Medical Centre, Dr Ken Ung, who specialises in adolescent psychiatry, as well as Reverend Chan Mei Ming, Assistant Pastor at Faith Methodist Church who trains people in trauma healing.

(Left to right) Joan Swee, Dr Ken Ung and Rev Chan Mei Ming lent their insights as counsellor, psychiatrist and pastor to help parents and caring adults talk children through trauma. Photos courtesy of Joan Swee, Dr Ken Ung and Rev Chan Mei Ming.

The panellists started the episode with the definition of trauma and went on to offer tips on engaging children who have been traumatised.

What is trauma?

Trauma comes in many forms. Death, like the one Joan and her sons experienced, is a form of trauma. But loss can be traumatic, too, said the speakers.

When Joan’s husband, Henry Chia, passed away, the family who had been living in Hong Kong returned to Singapore for good. With that move, Joan’s sons lost the only home they really knew, as well as their community – friends in church and in school. So they basically lost all that was familiar to them.

“Even food and special parks that we used to go for picnics – everything was taken away from them. We were facing multiple losses.”

The effort to adapt to Singapore was another traumatic experience.

“Even food and parks that we used to go for picnics – everything was taken away from them. We were facing multiple losses.”

“We had to adjust to multiple things, to new living conditions and, for my boys, the scariest thing was the Singapore education system.”

One day, her younger son returned home from school in tears. His classmates had teased him about his name. Bullying is another form of trauma.

Joan’s older son had ADHD, dyslexia, as well as difficulties in sensorial perception and fine motor skills. For him, the Singapore education system was traumatic.

“He couldn’t spell at Primary 2. He couldn’t even write half a page of composition.

“All he got was scolding and red marks in his exercise book. He literally tore his exercise book because it was full of red marks.”

Trauma is simply “something that is adverse, something not very pleasant”, Dr Ung summed up.

Explaining the science behind how trauma is perceived, he said: “When we experience trauma, the brain remembers trauma differently from other memories. That’s how God created our brain.

“The more sensitive you are, the more likely you are to be overwhelmed.”

“Traumas are stored in centres of the brain, very deep inside, called the amygdala and the hippocampus. They are designed to bypass the usual thinking centres.”

What is perceived as trauma differs from person to person.

In this way, trauma can be both subjective and objective, said Dr Ung. The same incident can happen to three people, but one may not be flustered, another only a little affected, yet another very affected.

“The difference in response has to do with a lot of factors. The resilience of the individual is one factor. Past events in another.

“The more sensitive you are, the more likely you are to be overwhelmed,” said Dr Ung.

What are the signs of trauma?

“When parents come to see me, I talk to them about two major things: One is about the distress the person may be experiencing. The other is symptoms.

“These are changes that we look for – changes in sleep, in dreams, avoiding things – these are all indicators that suggest that we are not coping so well,” said Dr Ung.

“There will be a lot more non-verbal manifestation in young children.”

Joan added: “If the child is not withdrawn, still going to school and engaging with siblings and friends, the child is not likely to be depressed.”

In younger children, the symptoms of trauma may be expressed differently.

Said Dr Ung: “Young children are much more likely to engage in mental defences that are not too common with older children.

“There will be a lot more non-verbal manifestation. They may create imaginary friends or block out the whole experience from their memory.

“They may become frozen. They may have a lot of temper tantrums because they are less able to process and express themselves.”

Ps Mei Ming added: “Because they don’t have the vocabulary, they may withdraw. They may not want to take care of themselves – basic activities, school work.

“Some may resort to hurting themselves, cutting, trying to express what they can’t express.”

“Sometimes, as neighbours, we need to be kaypoh (inquisitive) … because the child is defenceless.”

At times, if the cause of the trauma is home life, then relatives, friends and neighbours may have to be the ones who take note, said Joan.

She shared how she would often see her neighbour’s eight-year-old son at the stairway of her condominium, shirtless, sobbing and covered with cane marks. Often, he would be left to sleep in the lobby dressed in nothing but a pair of pants.

Together with a few neighbours, Joan reported the incident to the boy’s school. Soon after, the family moved away.

“Sometimes, as neighbours, we need to be kaypoh (inquisitive). We need to make a report because the child is defenceless. My heart breaks,” said Joan.

How do we get children to talk about their trauma?

Talking things through – getting children to process why they are feeling what they are feeling – is a very important step towards trauma healing, agreed the panellists.

Ps Mei Ming explained: “When we experience bad things, our hearts and minds can be wounded. It is important to take care of heart wounds so that inner healing can take place.

“And one way a heart wound can be healed is through telling someone about what happened and how it felt.

“It is important to take care of heart wounds so that inner healing can take place.”

“God ultimately is the one who heals but He uses people in the process.”

One way of getting children to open up is by showing empathy.

Dr Ung, who has experience as a court-appointed psychiatrist in acrimonious divorce cases, said: “Usually, it’s okay to talk fairly naturally, asking the child how they feel, saying, ‘It must be quite tough going through that’.

“Be natural, check with how they feel, try to empathise with that they are going through.”

As children share, it is vital to “listen well” to their replies.

Ps Mei Ming offered three listening questions to help that:

1. Can you remember what happened?

This helps to build rapport, and establishes facts and timeline.

2. How do you feel?

Healing takes place at the level of the emotions. Enabling children to name their feelings gives clarity to what would otherwise be vague feelings.

To help them name their feelings, caring adults can provide a list of words that describe feelings. The children can then circle the feelings they may have.

The panellists shared some words that caring adults can suggest to children to help them name their feelings:

- Scared

- Sad

- Confused

- Angry

- Worried

- Anxious

- Guilty

- Ashamed

- Lonely

- Helpless

- Numb

- Rejected

- Overwhelmed

For very young children, pictures of faces showing different feelings may be given, so that children can point to the face that describes their own state of mind.

Said Ps Mei Ming: “There are no wrong feelings. Have them understand that feelings are a natural response to things that happen in our lives. It is normal to have difficult feelings when difficult things happen to us.”

3. What was the hardest part for you?

Each person is different so there is a need to hear their individual answers, said panellists. This also helps them to clarify their strongest feeling and helps listeners know what the young person does when he or she has those feelings.

Another way to encourage a young person to talk is to help them name their losses.

Said Ps Mei Ming: “Get them to think of how these trying events have interrupted their lives, their plans, talk about their fears for the future.

A Bible passage like John 11:1-44 will “help them see that Jesus understands their feelings”.

“This helps them to recognise that, for them, life can be on hold, it can be stuck, it can’t go on, they don’t know how to go on. The feeling that there is no end – is this a new normal they are going to have to learn to grapple with?

“Then, encourage them to write down their losses and how each loss made them feel.”

It is only then that caring adults can “point them to a Bible spotlight”.

“At that point in time, sometimes they think God doesn’t care for them, He’s forgotten about them,” said Ps Mei Ming.

A Bible passage like John 11:1-44 will “help them see that Jesus understands their feelings”.

What if the child won’t talk?

The panellists advised patience and sensitivity.

Said Ps Mei Ming: “If they are resistant, they are actually not ready to talk.”

Joan agreed: “I want to come in here as a mummy – having children who have grieved and also because of the 20 years in Wicare walking with widows and young children – to say this: We don’t need to be anxious when children don’t want to talk. We don’t need to force it out of them.

“In the time I was in Wicare, I always want to empower the mummies to just bond with the children.”

For her, it was all about waiting for opportunities to engage her children, allowing the children to take the lead.

“If they are resistant, they are actually not ready to talk.”

“Children process grief differently from adults. So we can’t be trying to measure it from an adult perspective about how we expect them to do grief work.

“My younger one, the worst time for him was in the shower. He would be crying in the shower, saying, ‘I miss daddy so much.’

“I would tell him, ‘Mummy misses daddy, too. Come, let me hug you.’ I take it as it comes. If they express it, I can be with them and empathise with them.

“When they start asking questions, that’s the time they are willing to listen. When they express their anger, then you enter into that place, saying, ‘Tell mummy what happened?’”

Engaging through other modalities can also help a reticent child.

Said Dr Ung: “Young children may draw it out, paint or express themselves through play – sand work, play therapy.”

Ps Mei Ming advised that when children express their emotions through such means – for instance, drawing angry, jagged lines in dark colours – adults can hold their hands and say: “I would be very angry if my daddy died. Is that what you are feeling now?”

“When they start asking questions, that’s the time they are willing to listen.”

Helping to remove the stigma of being traumatised can pave the way for more openness as well.

Said Joan: “I was in Wicare for 20 odd years. I’ve met children who didn’t want others in class to know about their trauma for fear of being ostracised or bullied.

“Even teenagers are afraid.”

Underscoring the need for adults to be sensitive, Joan shared an incident involving a nine-year-old who had lost her father.

When the child wrote a composition for her school about her family, her teacher called her out and accused her of lying in her composition because she no longer had a father.

“The child was traumatised,” said Joan.

Editor’s note: This report is Part 1 of the Salt&Light Family Night episode on helping children through trauma. Look out for Part 2 of the report in the coming weeks.

A full recording of this episode will be available within two weeks. You can watch past episodes of Salt&Light Family Night on our YouTube channel here.

RELATED STORIES:

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light