“I wanted to tell their story”: Two sisters give voice to those who cannot speak for themselves

by Christine Leow // February 28, 2022, 5:44 pm

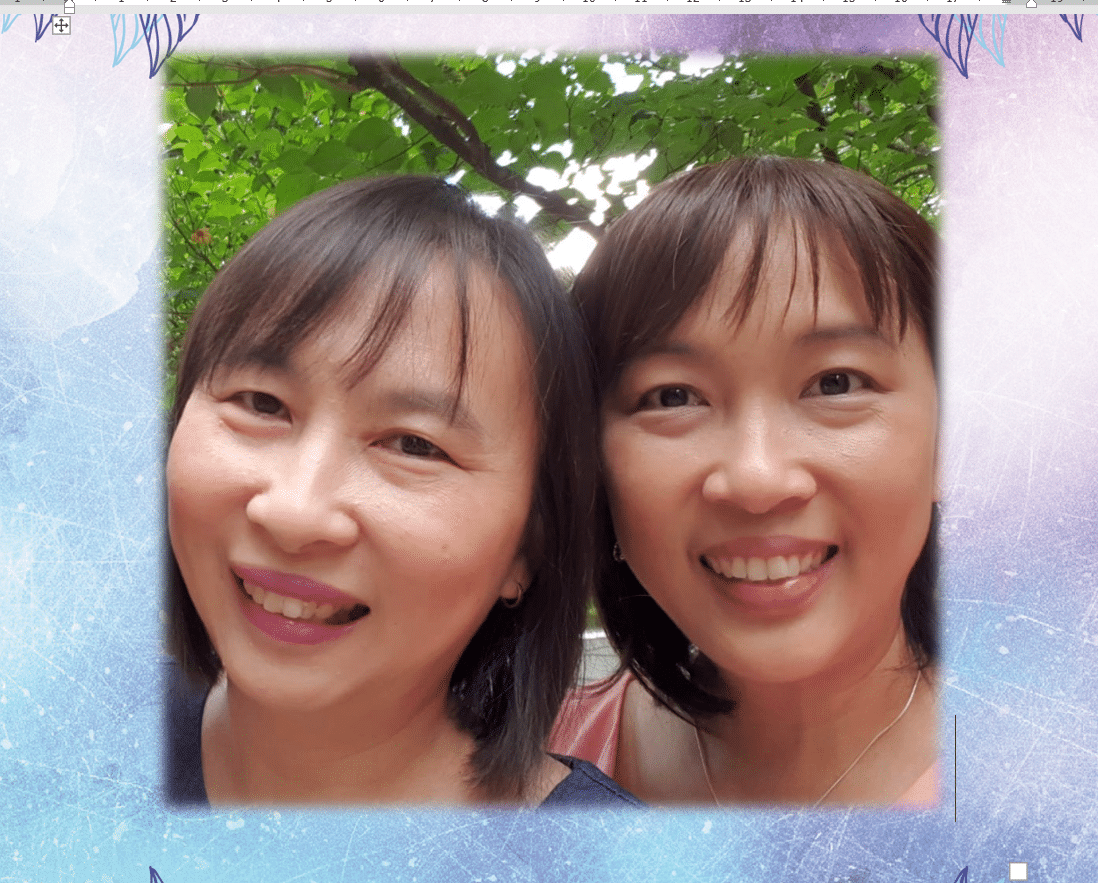

Sisters Sarah and Lois Yong grew up with a love for stories and a desire to serve others because of their parents who surrounded them with stories and showed them what it meant to serve others. All photos courtesy of Sarah and Lois Yong.

Some were children born with cerebral palsy, a disorder that affects movement and balance and, very often, speech.

Others had autism or intellectual disability and could only grunt and moan to communicate.

Then, there were adults who had survived strokes only to be robbed of their speech, and the elderly for whom age has meant a serious of debilitating conditions including Parkinson’s disease that changes the brain and slurs speech.

“I wanted people to know they have personalities, things to say.”

Every day for well over a decade, Sarah Yong, a speech therapist by training, would meet individuals with complex communication needs in her job as the Clinical Head of the Specialised Assistive Technology Centre (ATC) at the Society for the Physically Disabled (SPD).

“They had so much to say but they couldn’t speak. They were very intelligent, had a lot of personality, but there was no way to communicate all that. All of it was bottled up.”

Even as she helped them with augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), using computers, tablets and communication charts to give them a voice, her heart broke for them.

“I wanted people to know they have personalities, things to say. I wanted people to be aware of the role that we in society can play to help them express themselves.

“There is this verse in the Bible that talks about speaking out for those who cannot speak for themselves (Proverbs 31:8-9).”

Sarah considering what words to add to the ACC device.

Sarah did not simply want to champion their cause, she wanted to tell their story.

“As I looked, I didn’t see a lot of stories about people who had complex communication needs.

“And when I looked for stories about people in Asia, there were even fewer.”

That was how Sarah decided to rope in her younger sister, Lois, to write a book to “bring attention to this group of people”.

“Stories are a good way to educate people. Instructions can be threatening, but people like stories.”

Stories mother told

The Yong sisters grew up loving language.

Said Lois: “Our mother was a music teacher. Sounds and rhythms were very much a part of our lives.

“That translated into a love for the sounds and rhythm of language. There is a beauty in written and spoken English.”

“The first story I wrote was for my sister as a birthday present.”

Their mother, an English and History major, also imparted to them a love for stories.

Recounted Lois: “She would sit us down and tell the most amazing stories.”

In their home town in Sabah, Malaysia, in the 70s, blackouts were frequent. During those power outages, their mother would gather the girls and regale them with tales by candle light.

“She told us the story of Les Misérables when we were little,” said Lois.

“Yes, yes, about the candlesticks!” interjected Sarah.

That love for language and stories expressed itself early in the lives of both girls.

Only two years apart, Sarah and Lois were very close from young . Sarah, who had a love for teaching, would sit her younger sister down every day after school and teach her things she had learnt in school.

They would write stories and share them with each other.

“The first story I wrote was about a teddy bear party to throw for my sister as a birthday present.”

“To get each other’s opinions,” explained Sarah.

“As young as nine, I was writing my own fairy tales, stories others told us, about my relationship with people.

“The first story I wrote was about a teddy bear party to throw for my sister as a birthday present.”

Lois mused: “Only now do I have a vague memory of it.

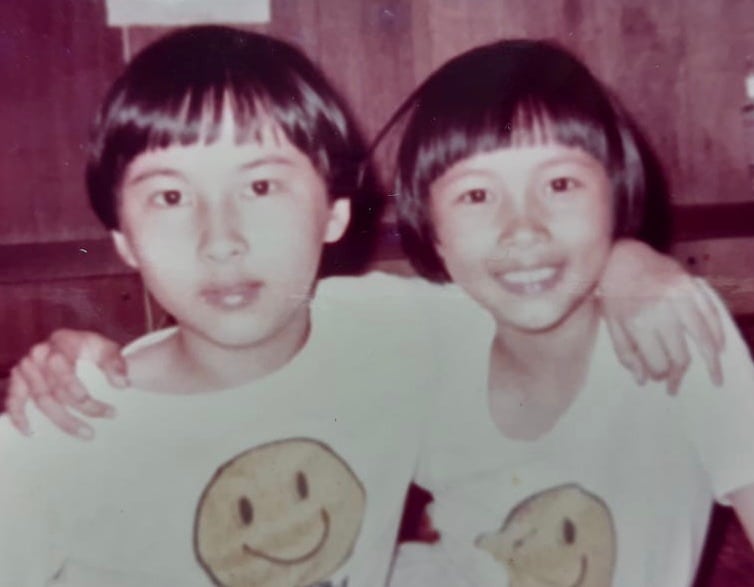

“One time, we went to the UK, Sarah was about nine and I was seven. She was like, ‘Everyday, we have to write a page.’”

Lois and Sarah on the United Kingdom trip when they wrote a page of a story a day.

Said Sarah with a smile: “I can be bossy.”

God in the flesh

But more than a love for literary pursuits, the sisters developed a love for people as well, thanks to the way they were raised.

“People from the deepest jungles of Sabah would stay in our house.”

“I grew up watching our parents have a heart for people, wanting to go that extra mile for people,” said Sarah.

Their father was a pastor and their home was often filled with visitors.

“We didn’t lock our doors,” recalled Lois. “Our home was on the same compound as the church and the school.

“During school term, if it rained, the kids would end up in our house. My mum would clothe them and feed them.”

Guest speakers from overseas would stay in their home instead of at hotels.

Lois and Sarah in their teens.

“They would take up a room in the house, and Sarah and I would move into our parents’ room.

“We got the most interesting people from all over the world including international theologians.

“People from the deepest jungles of Sabah who were part of interior mission fields would stay in our house as well when they came to town to get supplies.

“It was like the whole world came to our house.”

The girls, then only very young children, would sit and soak up the stories they told.

Beyond selfless hospitality, their parents also gave of their time. Sarah recalled how their parents had just returned from an overseas trip when they received news that someone they knew had been hospitalised.

Although it was quite late in the night, they dropped everything to visit the person.

“They could have said they would go the next day because it was late and they had just come back from a trip. But they went.”

“We learnt that putting people’s needs first, caring for others, is important.”

The sisters got front row seats to her parents’ love in action in other ways as well.

“We followed them on visitations, mission trips, went into the jungles (to visit interior missionaries) and bathed in the rivers,” said Lois.

Their parents would do this with great consistency and joy.

Said Lois: “They were never two people, like, nice on the outside, grumpy at home. They are so authentic, so genuine.

“It allows you to believe that there can be a kind God who really loves you. They gave us a glimpse of that.”

Added Sarah: “They also put us first. Other people’s needs were important but they also made time for us. We never felt neglected.

“We learnt that putting people’s needs first, caring for others, is important. It inculcated in me the desire for service to other people. I learnt to go that extra mile from them.”

Love that gives

To this day, all grown up and, for Lois, with grown children of her own aged 17 and 20, the sisters have not forgotten the faith imparted to them.

“A lot of these children she worked with touched her heart.”

Lois and her husband now live in Boston and are part of their church’s outreach to the marginalised. Just before the interview with Salt&Light, she had been busy re-homing Afghan refugees.

Sarah was part of a team that helped set up a ministry for special needs in her church.

“My parents’ genuine faith really impacted me. I saw that faith has to be lived out, it has to be real.”

The idea of writing a book about the voiceless people who crossed her path was many years in the making.

“I had been jotting down notes on my phone.”

Sarah had even written an essay on the topic.

When the pandemic happened and the world went into lockdown, she suddenly found she had the time to turn the essay into a book.

“I wanted someone who understood the protagonist. And my sister is very artistic.”

Her first thought was to make it a book for children.

Said Lois: “A lot of these children she worked with touched her heart. And the essay she wrote was about a little girl.”

Sarah’s next thought was to co-write the book with her sister as they had often done in their childhood.

“I thought it would make a really nice picture book. So, we should have illustrations. I wanted someone who understood the protagonist, and the subject matter.

“My sister is very creative and artistic, and I had shared a lot with her about the disabilities. So, I thought to ask her.”

Piped in Lois: “Also, we didn’t have the money for an illustrator.”

The voice of Mei

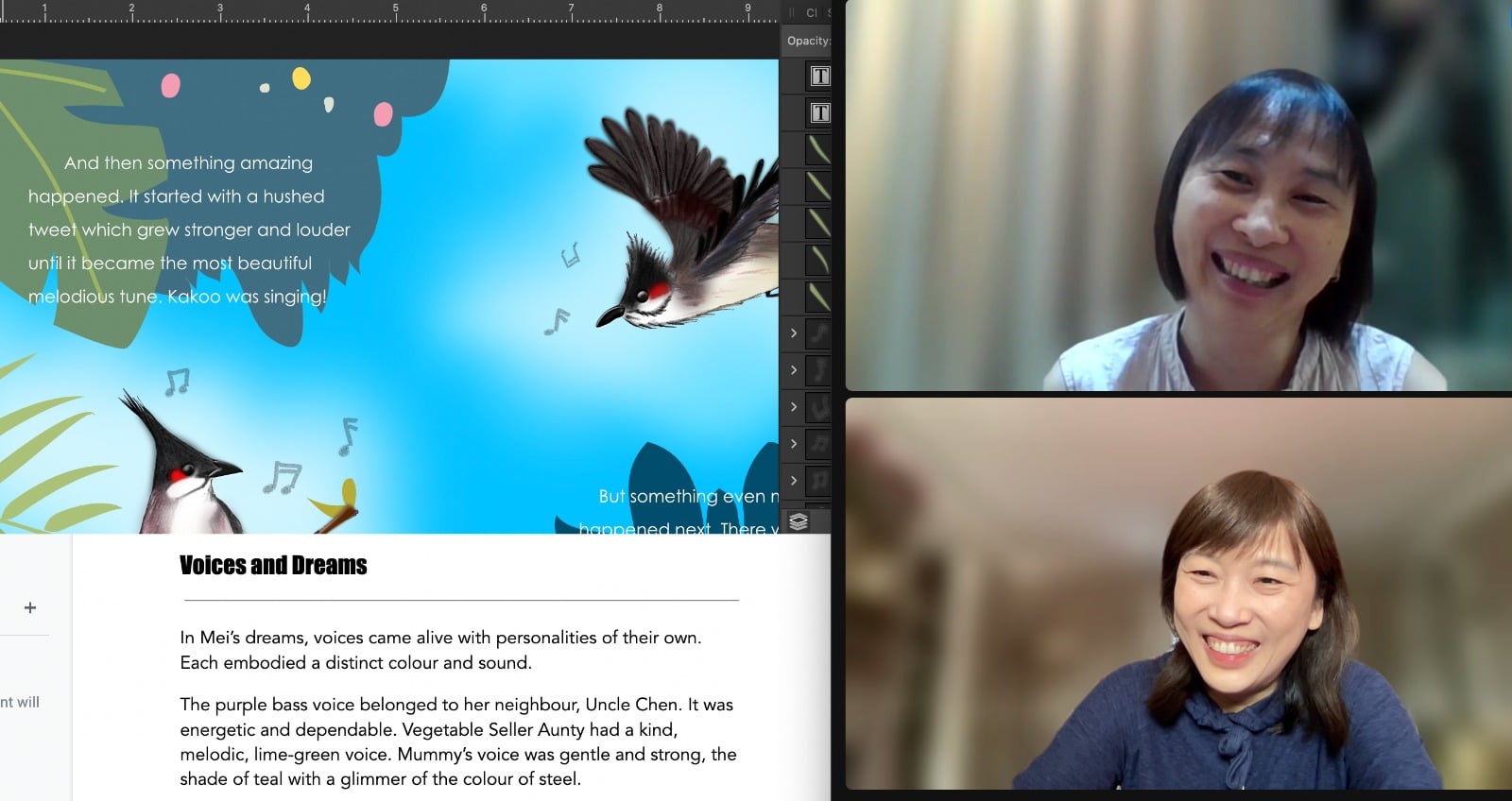

Because the sisters live apart – Sarah in Singapore and Lois in Boston – it took over a year to get the book out.

Said Sarah: “I would write from a disability advocate perspective and Lois would give me the perspective of the community at large.”

With Lois’ input, the characters of the protagonist’s mother and grandfather were fleshed out more.

Separated by time and space, the sisters nonetheless were able to work together on the book, with Sarah (top) writing the story and Lois giving her input and doing the illustrations.

Said Sarah: “That helped to make it an accessible story from everybody’s point of view.

“I hope that, eventually, there will be a Mei who can tell her own story.”

“Lois made it a better story. It’s a special thing working with my sister.”

In the end, because they wanted to “go into the character and express her feelings more”, the book was pitched at primary school children instead of pre-schoolers as originally planned.

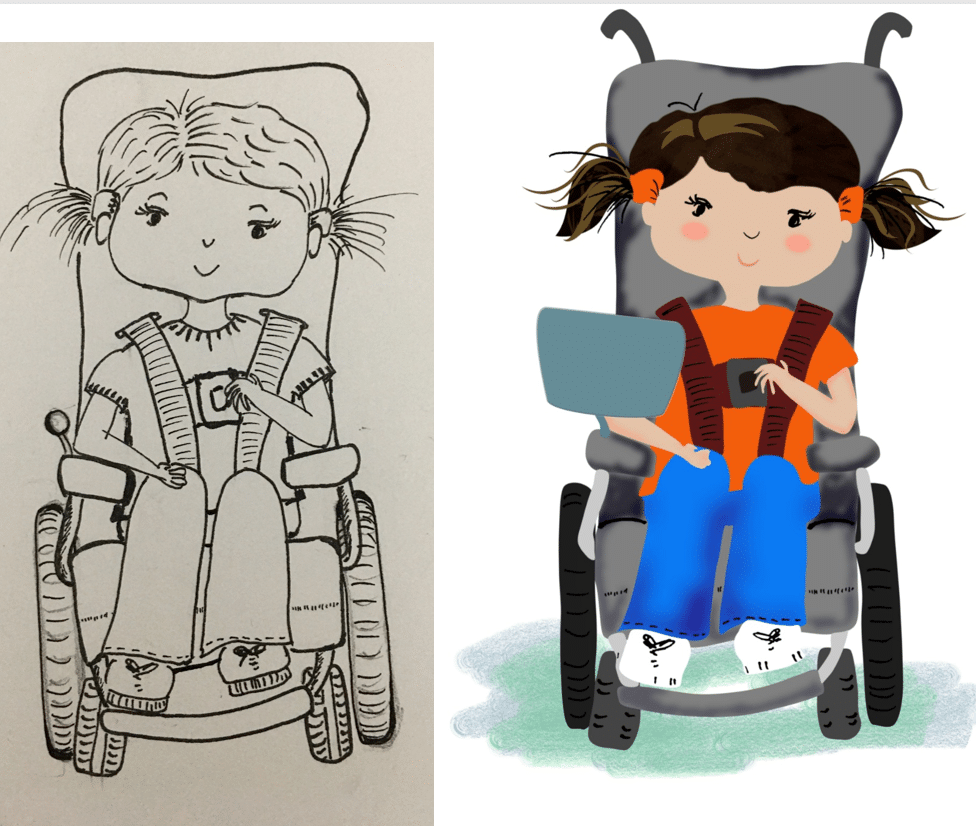

A Voice of Her Own tells the sweet story of 10-year-old Mei who has cerebral palsy. Smart and imaginative, she is, nevertheless, trapped in her own world because she cannot speak clearly and no one understands her.

Then, Mei is given a talker, an electronic device with pictures and words that allows her to express her thoughts with simple clicks.

Though fictional, Mei is the amalgamation of all the children whom Sarah has worked with in her job.

She felt she had inserted the key and unlatched the door and she was free.

With her newfound freedom, Mei is empowered to help her pet bird Kakoo find his freedom.

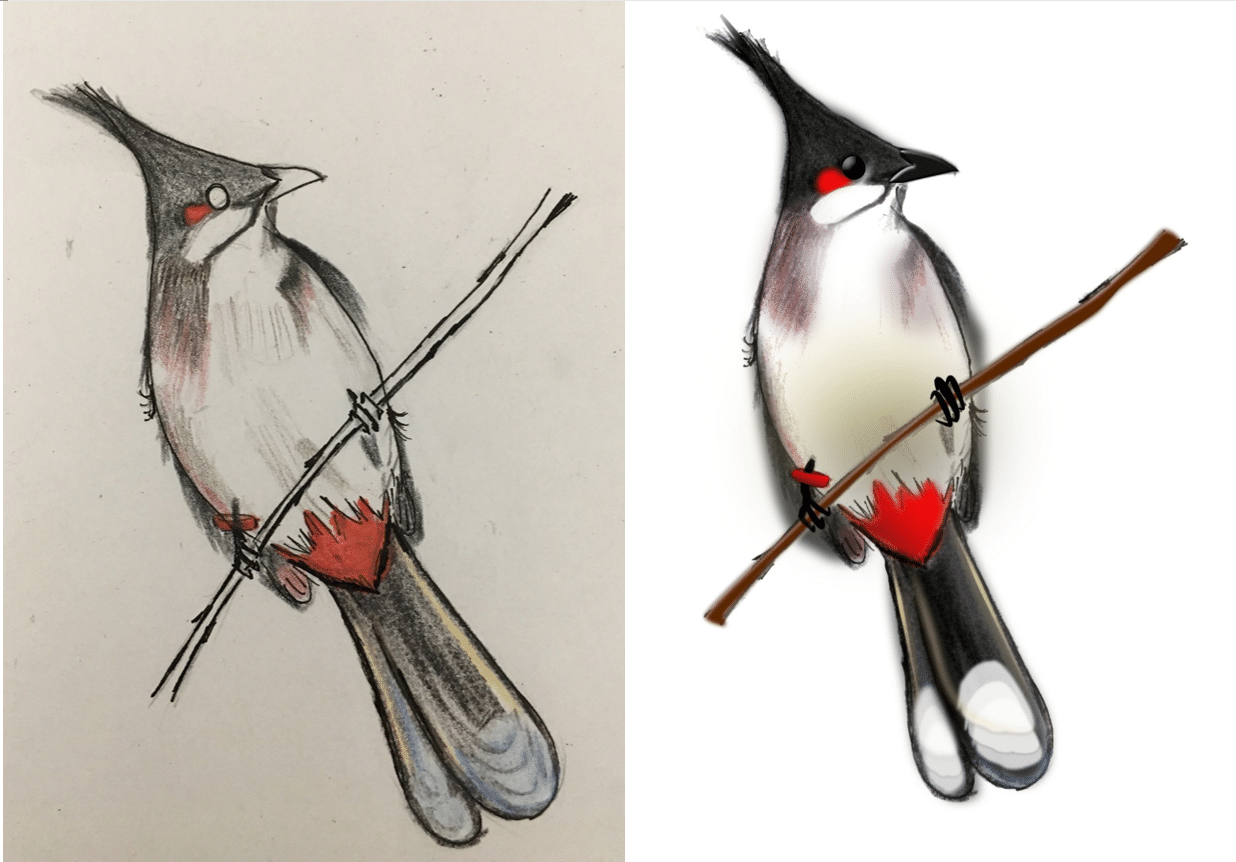

To make sure she got the bulbul bird right, Sarah went to the Jurong Bird Park to speak to the park rangers.

Kakoo, Mei’s pet bird, whom she helped after she finds her own voice.

“The rest of the story was based on real encounters. But the part about each voice having a distinct colour we embellished,” said Sarah.

Self-published in October 2021, the book is available in both soft and hard copies.

“It became a story about the inspiration and courage to find our own voice.”

Said Sarah: “From a disability advocate perspective, I really wanted to tell the story of this population who is not being heard, who needs to be heard.

“My other hope is that this book would speak to people and caregivers who are in a similar situation as the protagonist.

“I hope that, eventually, there will be a Mei who can tell her own story.”

But the book has a message for the general audience as well.

Said Lois: “When we were done, we realised it was a story about all of us who are afraid to speak up, or have something to say and cannot say it.

“It became a story about the inspiration and courage to find our own voice, not just about a kid with a disability. It is a story for all of us.”

RELATED STORIES:

“Nigel and Donavan, one day we’ll meet again,” say parents of boys in tragic Tampines accident

Three children with fatal genetic disorder, yet David Lang sees God’s sovereignty

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light