“When you’re broken, that’s when you surrender to God”: Former politician Idris Jala who has faced labour strikes, bomb threats and a hostage situation

Emilyn Tan // August 23, 2023, 1:48 am

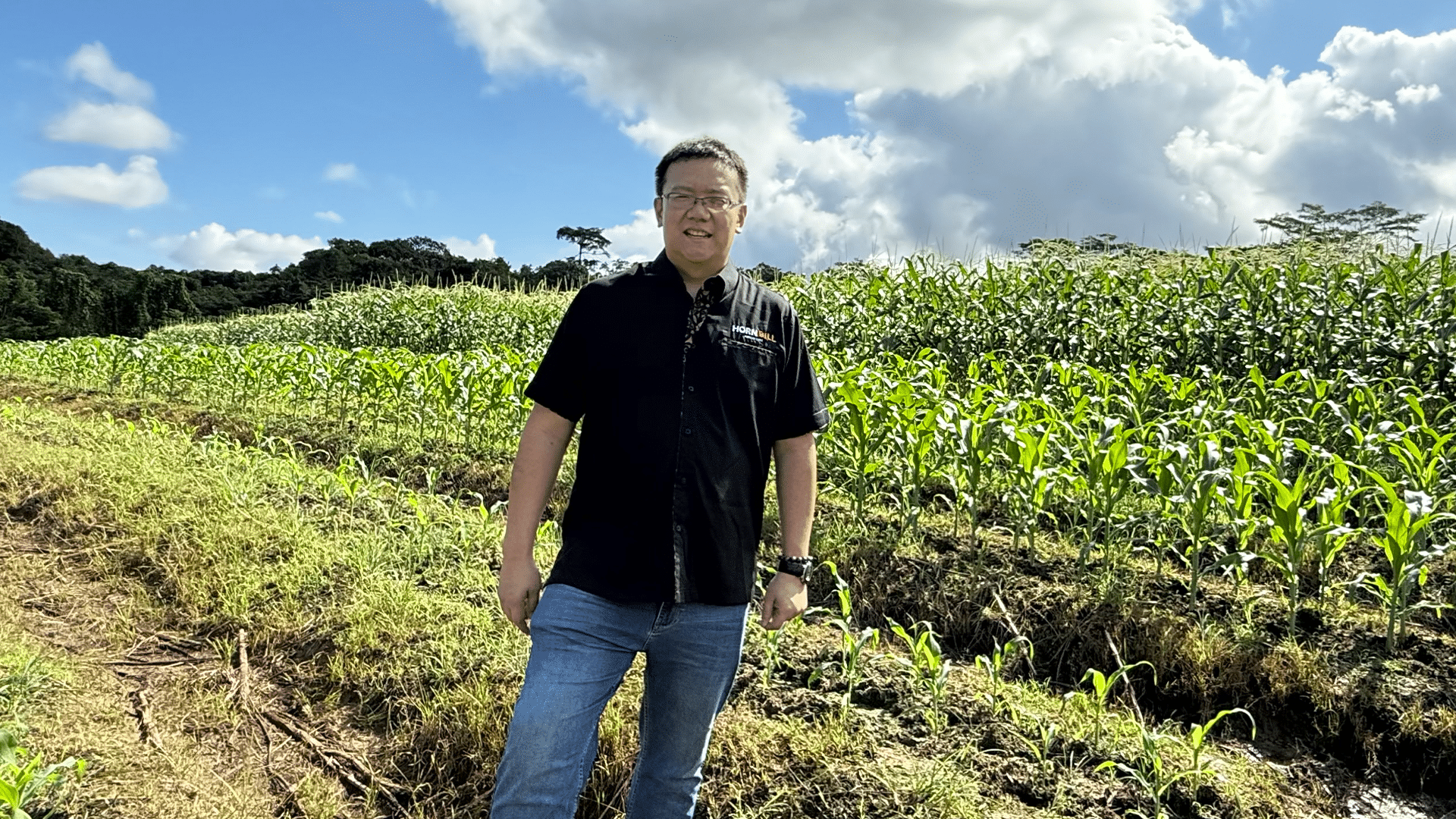

While Idris Jala is highly successful in the public and private sectors, he counts being "absolutely broken" as a pivotal point in his life's journey. "That's when I understood the idea of surrender to God," he said. Photo from Pemandu.org.

The decision to enter politics in his home country of Malaysia was not one Dato’ Sri Idris Jala made lightly. To him, the pressing issue was: “How do I make sure I am in the world but not of the world? How do I make sure that the world does not live within me?” (John 17:15-16)

The Founder/President of Pemandu Associates, a consultancy firm specialised in corporate turnaround and national transformation, has held various top corporate jobs internationally as well as serving as a Minister in the Malaysian government.

So known is he for his ability to turn floundering businesses around that, in 2014, Bloomberg rated Jala among the top 10 most influential policy makers in the world.

Idris Jala (centre) speaking at the Eagles Leadership Conference this year. Photo courtesy of Eagles Communications.

“I’m a corporate guy,” he told the rapt audience at the Eagles Leadership Conference in July this year, at which he was a speaker at the plenary discussion, “The Rise and Fall of Organisations: Lessons on Leadership”.

“When I was invited to become a minister, I actually said no, because I didn’t feel that was the right thing to do.”

“How do I make sure that the world does not live within me?”

However, he allowed himself to be persuaded to think it over, and took five days off work to seek the Lord with his wife, Datin Sri Ngan Yue Pang-Jala.

“We started reading the Bible from right from Genesis – every book, just because God says He speaks to us through the Word,” he shared.

“We went through Exodus, Deuteronomy, and by the time we reached Nehemiah, we said, ‘This is it.’”

The Old Testament statesman’s manner and method resonated. Even so, “we had to devise very specific boundary conditions. Ngan and I spoke about it very clearly.”

The caveats Jala set forth were:

- He did not want to become a member of any political party.

- He did not want to answer questions in Parliament.

- He did not want to participate in any political rally.

All of these were “so that I can focus on the work. Only when those things were ticked, then we were prepared to go and do it”.

His terms were agreed to, and he served as a Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department from 2009 to 2015 under the premiership of Najib Razak.

It turned out to be a season during which his already-rising profile was propelled to greater heights.

Full-circle turnarounds

Prior to becoming Minister, Jala had turned the troubled Malaysia Airlines (MAS) around, and before that, various arms of the petrochemical giant, Shell.

At MAS, which was fully government-owned when he was appointed CEO in December 2005, he insisted on a profit and loss (P&L) statement for every flight for a whole year.

Technocrat Idris Jala, who was CEO of Malaysia Airlines from 2005 to 2009, is credited with turning the airline’s ill fortunes around. Photo by Samuel T on Unsplash.

That meant a whopping 110,000 P&L statements. “My finance director nearly fell off his chair,” he said.

“What is the solution? Get rid of those two flights.”

He also gathered MAS employees into teams (which he called “labs”) along geographical lines and instructed them to come up with region-specific solutions based on their analyses of their respective P&L statements.

They quickly realised that two flights to London’s Heathrow Airport were profitable every day, while two consistently were not. “What is the solution? Get rid of those two flights.”

Flights from Kuala Lumpur to Sydney left before passengers from Europe via London arrived, so no connections could be made. His tack: “Change the schedule.”

Profitability was but an internal upheaval away.

Jala offered: “When you look at the P&L with that level of detail, you know the answers. But you can see it only if you drill it down to the lowest common denominator.”

Revival fire

Such astuteness had its beginnings tinged with the supernatural in his hometown of Bario in East Malaysia.

“We were so remote, I didn’t know a world existed beyond the mountain.”

Jala, now 65 and the CEO of global consultancy Pemandu Associates Sdn Bhd, was born and bred in Bario at a time when the village in the Kelabit Highlands was largely jungle. Border confrontations with the Indonesians were frequent, and the British government sent in its troops to provide a deterrent.

Among the things the foreigners did for recreation was watch movies, which were screened in the open fields. The villagers watched curiously from the other side of the barbed wire fences that surrounded the army camps.

“We were so remote, I didn’t know a world existed beyond the mountain,” Jala recalled. “I thought Elvis Presley was left-handed, because we were watching from the other side!

“The soldiers told us the passport to see the world beyond the mountain was education. So, for me and my friends, failing an exam was like consigning yourself to death.”

“Everyone was touched by God. And we didn’t want to stop praying.”

Preparing diligently in 1973 for their Form 3 exams, 15-year-old Jala and a friend would break the monotony of studying by reading their Bibles and praying.

“The prayer became longer and longer. And then the reading the Bible became longer and longer – more than geography and history.”

In their second week, “we just broke down in tears”, he said.

“We were on the floor, crying. We told ourselves never to tell anyone about this, because it was so unnatural. What we didn’t realise was that the same experience was happening among the boys and the girl in my village.”

The next Sunday at their school’s Christian Fellowship, the Holy Spirit touched individual boys and girls, and then the whole village. “Everyone was touched by God. And we didn’t want to stop praying.

“I remember it was 3 o’clock in the afternoon and we went on until 10pm.”

“People reconciled, marriages came back. People who were quarrelling over land returned the land.”

Their headmaster wanted to put an end to all that was going on. With two others, Jala stood his ground and prayed for him. “The prayer lasted no more than one or two minutes, and he was on his knees praying.

“The next day and the next and very next, nobody was studying; we were praying.”

Jala even walked for five days into the jungle to preach. His sister walked further, for six days.

“We were out there evangelising. The power of the Holy Spirit was incredible. I didn’t need to spend 10 minutes to preach. Just one verse from the Bible and prayer, and everybody accepted Christ. That’s how it was.

“People reconciled, marriages came back. People who were quarrelling over land returned the land, and there were no land disputes.

“That period was like a foretaste of what’s in heaven. That moment was the moment of anointing.”

Extreme measures

When he left Bau to go to university, he carried with him that stirring experience, adding its indelible mark to a “burning desire to win” (the opposite of Singapore’s “kiasu”, or “hate to lose”).

“If the bomb had exploded, people within a four-kilometre radius would have died.”

His take: “If you have a burning desire to win, or hate to lose, the consequence is exactly the same: It means you take extreme measures.”

He was later to find himself extended to the most extreme in Sri Lanka, where he was sent by Shell to reverse the oil company’s huge losses there.

“I was an impressionable young man,” he said. Although he had the title of Managing Director he was, arguably, ill-equipped for the harrowing set of challenges that awaited him.

Shell was the only supplier of cooking gas in the country at the time, yet “we had lost so much money and everyone was defeated”.

“When you’re broken, when you defeated, that’s when you ask God to help you.”

There were almost-daily labour strikes. His transport manager was taken hostage. He received word that an underground bomb was planted beneath 1,800 metric tons of gas.

“If that had exploded, people within a four-kilometre radius would have died.”

On the home front, his wife was having panic attacks.

“I felt absolutely broken,” he confessed. “I was on my knees, crying, because I realised I absolutely didn’t know what to do.

“That was a pivotal moment in my life journey. When you’re broken, when you defeated, that’s when you ask God to help you.

“I understood in Sri Lanka the idea of surrender to God, the idea of asking God to take over. I would say 80 to 90% of what happened to me had nothing to do with me. They were all the works of God.

“That was a lesson learned.”

Innovation is key

Subsequently, he took just six months in 2003 to reverse Shell Malaysia’s losses. The game-changer: Innovation.

“The plant that we had in Bintulu was the first plant in the history of oil and gas that produced diesel and kerosene from natural gas. All diesel and kerosene had come from crude oil up to that point.”

The company expanded into Europe and was the official supplier of eco-friendly diesel to the 2004 Olympics in Athens.

“Our kerosene had no smell. There was no soot and the diesel was smoke-free. People were queueing for our product.”

That December Jala bought iPods for his entire staff, “including the driver, the guards, the tea lady” in acknowledgement of their collective effort.

“Throughout my journey of life, the central point was this idea of doing the impossible with God.”

“I wanted everybody to say, ‘We have now reached the first pinnacle. There are many more to climb.’”

The “very simple” idea of innovation, or strategy-driven transformation, was to him a matter of a three-step process:

1. Set yourself an impossible goal.

“That goal must be impossible to achieve in your current way of doing (things). You have to chart a completely new path.”

2. Embrace a new way of working.

“Because it’s impossible to achieve, everyone will have to innovate. This idea is absolutely key.”

3. Seek divine intervention.

“For Christians, the third point should be the first. We are blessed, we have God living within us.

“We don’t really believe it. We don’t put faith in action. That’s why we never achieve the promises that God gave to us.”

“To my mind, there is no excuse for us to say that all these things cannot be done by human beings, because in Luke 1:37 it says, ‘With God, nothing is impossible.’

“We don’t really believe it. We don’t put faith in action. That’s why we never achieve the promises that God gave to us, promises of the land of milk and honey (Exodus 3:8). He wants us to live life here on earth to be a glimpse of what heaven is about, to be the best versions of ourselves.

“Throughout my journey of life, the central point was this idea of doing the impossible with God, living with Him.

“Never despair when God does not give us what we ask for. He knows if it is going to be bad for you. Always the counterbalance is: God knows.”

Beware the grey areas

Jala counselled: “In leadership, you will have three circles of things that you do.

“Be very careful, because your conscience gets modified over time.”

“The first is to do the things that are right. This is called a white circle. The black things are corrupt, wrong, illegal. That’s a very easy distinction.

“Unfortunately, there are a lot of grey circles: (Things) not exactly correct, not exactly incorrect; not exactly legal, not exactly illegal.”

How do we deal with this?

“Conscience, conscience, conscience,” he said as he offered a three-step approach:

- Many people: “Never decide on your own,” he cautioned. Bring the issue to a group of people so that many consciences are given voice. “If you’re doing it alone, what you think is grey actually is black, because if you get used to seeing things like that, over time, what used to be black becomes grey. Be very careful, because your conscience gets modified over time. That’s why you need other people to really put you on the straight and narrow.”

- Many consciences: “You must write down the facts of the case, the options available, the pros and cons, and why you choose Option C instead of A and B. Justify why you choose that option.”

- The litmus test: “If this document is leaked out to social media, can you defend it – yes or no? If you cannot defend it, that is not the right ethical action.”

“If you do this, you can handle a lot of ethical issues. That is my panacea for all these things.”

RELATED STORIES:

Why Malaysia will never be the same again: MP Hannah Yeoh on the “rebirth of a nation”

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light