“Nothing in Scripture says that if you have dementia, you cease to be a disciple”: Here’s how the Church can remember those who forget

by Gracia Lee // January 17, 2022, 4:16 pm

Having conversations about dementia is needful, given that one in 10 people in Singapore aged 60 and above suffers from the ailment. Photo by Jixiao Huang on Unsplash.

In hospital for dementia, Aunty May (not her real name) was known to be cheerful and friendly – until her behaviour changed abruptly one day.

Seemingly in a panic, the elderly woman began pacing up and down the ward, repeating the same word over and over again: “God. God. God.”

Unable to understand why she was saying this, people around her assumed she was having some sort of psychotic episode.

But when a thoughtful nurse decided to slow down to listen, it dawned on her what the elderly woman was trying to say.

“You might forget God as you move along your journey into dementia. But God will never forget you.”

“Are you afraid that you’re going to forget about God?” the nurse asked. Aunty May stopped. Looking the nurse in the eyes, she replied: “Yes.”

Having been a Christian all her life, Aunty May’s identity had been grounded in knowing and worshiping God. And now, she was faced with the paralysing fear that she would forget Him.

“Well, it’s possible. You might forget God as you move along your journey into dementia,” the nurse replied.

“But God will never forget you.”

Immediately, a sense of peace washed over Aunty May’s demeanour. She no longer paced. She was no longer frantic.

She could now rest assured, knowing that the most important thing in her relationship with God was not her memory of Him, which was quickly slipping away, but the gift of His grace.

Dementia in our pews

Professor John Swinton was recounting this real-life story at last December’s online webinar, Including People with Dementia in Churches: Theology and Praxis, which was organised by Koinonia Inclusion Network (KIN) and the Biblical Graduate School of Theology (BGST), through the Centre for Disability Ministry in Asia (CDMA).

Supported by St Luke’s Eldercare and the Anglican Diocese of Singapore, the webinar provided a biblical perspective on how we should view people with dementia, and how the Church can continue discipling those with it.

Prof Swinton, the webinar’s keynote speaker, is an ordained minister and a professor in practical theology and pastoral care at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland. He is also the author of Dementia: Living in the Memories of God, which in 2016 won the Michael Ramsey Prize for theological writing.

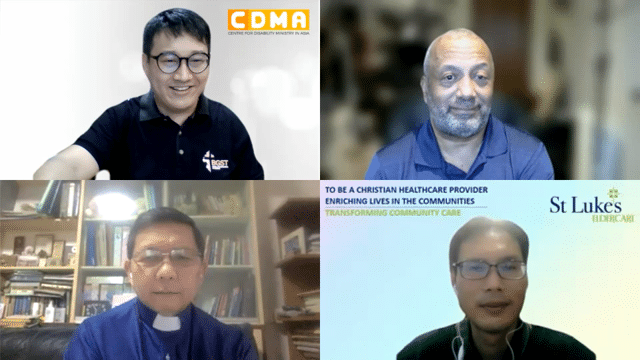

The webinar included (from top right, clockwise) keynote speaker Professor John Swinton, and panellists Dr Lester Leong, clinical director of St Luke’s Eldercare, Venerable Wong Tak Meng, Archdeacon for Community Services at the Diocese of Singapore, and Leow Wen Pin, director of CDMA. Photo courtesy of KIN.

Having conversations about dementia is needful, given that one in 10 people in Singapore aged 60 and above have the ailment, according to the 2015 Well-Being of the Singapore Elderly Study by the Institute of Mental Health.

With an increasingly ageing population, churches will see more and more members with dementia sitting in their pews. How should we love and care for them? And how can we continue to include them in the body of Christ?

You are, because God loves you

Before we answer these questions, it is important that we learn to see people with dementia the way that God sees them, instead of the way culture or the world does, said Prof Swinton.

“If she’s not the person that she used to be, then who is she? And why should we love her?”

He noted that people who know a person with dementia often say things like: “She’s not the person that she used to be” or “He’s not the person I knew”, as if that person has somehow disappeared.

This is a dangerous way of thinking, as it assumes that who we are is based on our intellect and reason, said Prof Swinton, adding that this is largely influenced by Western culture and the “I think, therefore I am” philosophy by René Descartes.

It is a troubling view, as it may lead us to see people with dementia as “lesser” people, or reduce them to mere victims of their condition, he said. “If she’s not the person that she used to be, then who is she? And why should we love her?”

Urging participants to look to what the Bible says about our identity, Prof Swinton said: “You are, because God loves you. Not because of anything you do. Not because of anything that you are able to do in the future. You are, because God loves you.”

Receiving care is a calling too

When we understand that the identity of a person with dementia is not found in their neurological capacity, but in God, we will see them as valuable members of the body of Christ, which comprises both the weak and the strong (1 Corinthians 12:12-27), said Prof Swinton.

He challenged participants to think about what discipleship looks like for a person with dementia, and how the Church can help them continue following Jesus.

“What does it mean to have dementia and to have a calling from God?”

“There’s nothing in Scripture that says if you are 92 years old and you have some brain damage, you cease to become a disciple with a vocation. So, our task is to think: What does it mean to have dementia and to have a calling from God?” he said.

He added that one’s calling from God does not necessarily include doing something. Rather, it can simply be just being.

He pointed to the creation account in Genesis, where God gave Adam the responsibility to care for and tend to the world (Genesis 2:15).

“A primary responsibility of human beings is to care … So obviously, that also means to receive care. To care and to receive care is something that is fundamental to what it means to be a human being,” he said.

“When you get to that point in your life where all you can do is receive care, you don’t lose your dignity and you don’t lose your vocation. You simply live in an aspect of what it means to be a human being, and ultimately what it means to be a creature.”

He added that while work – which was commanded by God – is important, having peace, shalom, and rest are also crucial to our spiritual life.

When we rethink our mental script of spirituality to include these aspects, we will realise that people with dementia have not lost their spirituality, but have merely moved into a different phase of it, he said.

Worshiping through muscle memory

It is thus important to continue including people with dementia in the Church and enabling them to worship God, instead of isolating them from the community, said Prof Swinton.

“One of the things we often forget sometimes is that people with dementia don’t stop being spiritual beings simply because they have brain damage,” he added.

While we may wonder how much of a church service they can understand, we should not underestimate their ability to pray, participate or be present in a worship service, he said.

“At a human level, we may struggle to connect. But God doesn’t struggle to connect.”

He recounted a story told to him by a chaplain friend, who had been unable to connect or communicate with an elderly woman with dementia named Beatrice.

One day, the chaplain suggested praying together. Beatrice did not respond. But when the chaplain started reciting The Lord’s Prayer, Beatrice began to pray too.

“My friend couldn’t work out what she was saying, but she knew that she was praying. And she continued to pray until my friend said amen,” said Prof Swinton.

“Isn’t that interesting? Even though Beatrice couldn’t be understood by you or me … she could be heard by God. Every time we pray, Scripture tells us: God hears us. God responds … At a human level, we may struggle to connect. But God doesn’t struggle to connect.”

Prof Swinton also noted that while people with dementia may have difficulties with recalling memories, they may still be able to remember physical actions that they’ve practised over the years, such as raising their hands in worship or clasping their hands in prayer.

“Their bodies continue to worship Jesus even though perhaps they can’t remember Jesus in the way they used to. That is a very powerful thing,” he said.

Re-membering church members

Noting that people with dementia often struggle with a loss of connectedness to themselves, God and the community, Venerable Wong Tak Meng, Archdeacon for Community Services at the Diocese of Singapore, suggested practical ways to include them in church services.

As familiarity is important to persons with dementia, we should try to keep things like the physical setting, worship flow and liturgy the same, said Venerable Wong, who was a panellist at the webinar. If this is not possible, caregivers can talk them through what they can expect to see or experience prior to the service.

Worship leaders and preachers can also be sensitive to the language they use, for example by including simple and familiar creeds, prayers and songs, and refraining from using references to high-tech or recent events.

To remember is to “re-member” them, which is “to re-affirm that they are a member of us, the body of Christ”.

“We must continue to trust that God can connect with people with dementia through the simplest means, through the simplest expressions of faith and truth, especially familiar truths,” he said.

After the service, fellow church members can greet and affirm them, which will help to make them feel included, he added.

Venerable Wong also pointed out the importance of extending pastoral care to caregivers and working closely with them, especially when the person with dementia is exhibiting certain behaviours that may be deemed disruptive.

He said: “If I’m a caregiver and I have one episode, I may be discouraged from ever bringing my parent to church ever again. So, I think that pastoral conversation has to say, ‘You know what, that’s okay. Let’s figure out what’s causing the distress.'”

However, while it is reasonable to find a solution that reduces disruption to other worshipers, Prof Swinton stressed that “abandonment is never appropriate”.

“We should never pull people out so that we can go on and worship,” he said.

These efforts are ways that we can remember people with dementia, added Venerable Wong. To remember is to “re-member” them, which is “to re-affirm that they are a member of us, the body of Christ”, he said.

He added: “We want to encourage each other not to go away, but through whatever way possible – perhaps a church visitation ministry, listening to their repetitive stories, sharing familiar songs and Scripture, praying together simple prayers – practise the art of re-membering.”

I’m glad you exist

Closing his keynote speech, Prof Swinton urged participants to reframe and redefine dementia. While it is a neurological condition and a place of loss and sadness, this is not all there is to it, he said.

Dementia can also be a meaningful human experience and an opportunity to challenge our assumptions that human beings are defined by their memory and intellect.

It is also an opportunity to learn how to care for one another better, as well as understand the meaning of discipleship more fully, said Prof Swinton.

In the book Faith, Hope and Love, author Josef Pieper writes: “Love is saying to the other person: It’s good that you’re here. I’m glad that you exist.”

Said Prof Swinton: “You can include people in a community quite easily, but in order for them to belong, you need to miss them. They need to have a space within your community, where if they’re not there, people will go look for them, people will go visit, people care.

“When you have that kind of community of belonging … then the recognition of God’s remembrance becomes a reality.”

FOR MORE STORIES ON DEMENTIA, READ:

Time was running out … Would her dad say yes to Christ before dementia claimed his mind?

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light