A 10-cent bet led to his 24-year gambling addiction

by Gemma Koh // August 23, 2022, 5:38 pm

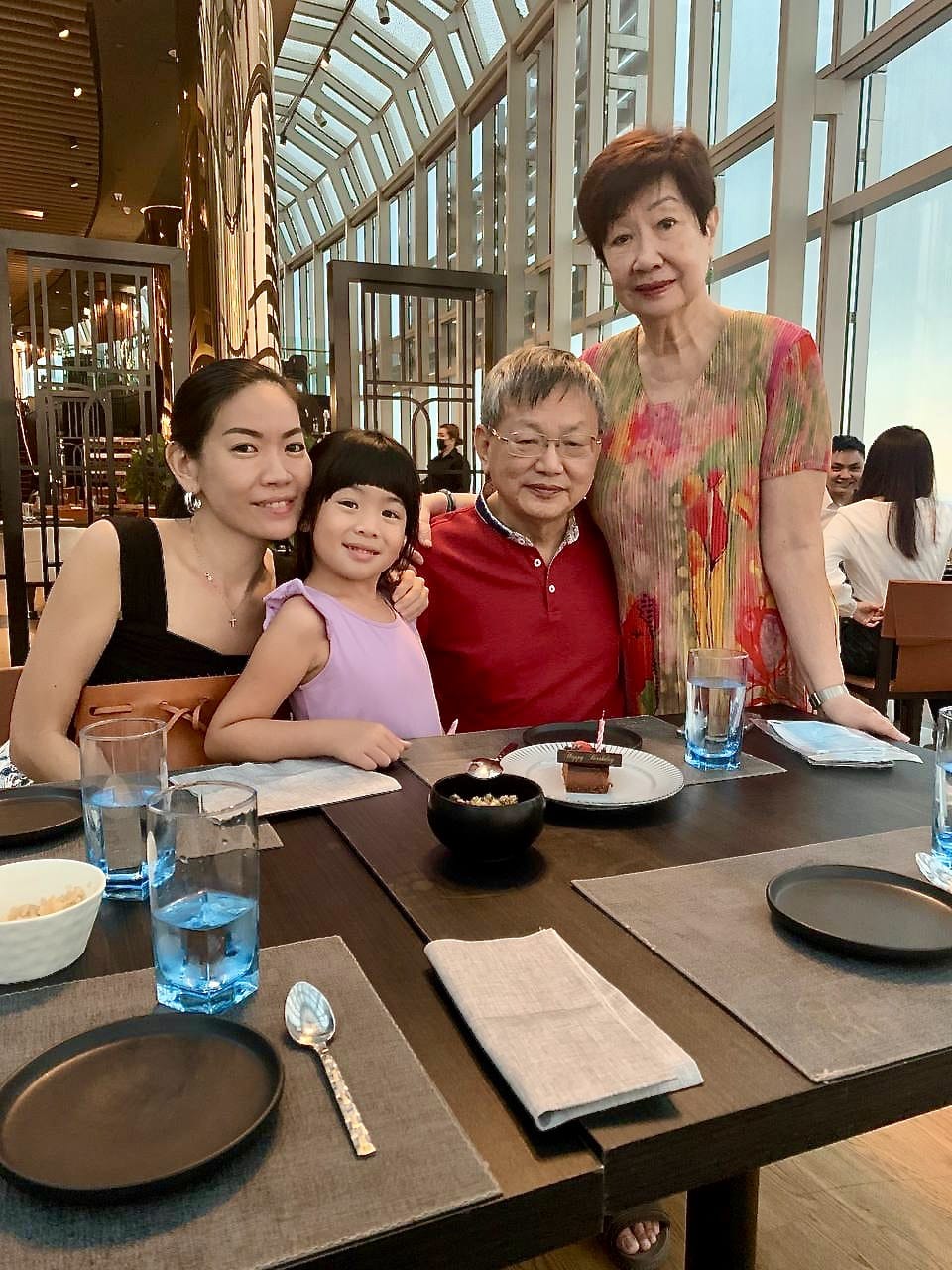

What started as a small bet turned into a long-term struggle for Benny Ong (pictured with wife, Anne). All photos courtesy of the Ong family.

Growing up, Benny Ong lived with his extended family above his grandfather’s shophouse in Rochor Road.

In total, 26 members from five families slept in five cubicles made from flimsy wooden panels.

“If you gave it a kick, the cubicles would fall apart,” Benny recalled. “And all 26 of us shared one makeshift toilet.”

The next morning, he won $5 from his 10-cent bet. “It was so easy. I wondered why I didn’t put in 20 cents.”

One evening, as 10-year-old Benny was about to go to bed, his auntie knocked on his partition.

“She handed me a slip of paper and $5, and told me to buy two numbers for her,” Benny, now 76, recalled.

The game was chap ji kee (Hokkien for 12 sticks) – a private, illegal lottery that many housewives at the time were fond of playing.

Benny asked his aunt: “If you strike, how much will you get?”

She said she would get $250 from the $5 bet.

Intrigued, he put in 10 cents – his daily allowance – with his aunt’s bet.

That bet was the start of a 24-year addiction to gambling.

The next morning, his aunt won $250 and he got $5. It looked like they had picked the winning combination of two numbers from 1 to 12.

“Sixty-five years ago, $5 was a lot of money,” he said. “I was so excited. It was so easy. I wondered why I didn’t put in the 20 cents I had in my pocket.”

When he was 15, an uncle taught him to bet on horses.

The next evening, Benny’s aunt gave him another two numbers and $10. “I raised my stake to 20 cents,” he said.

“The following morning, we hit the jackpot. She got $500 and I got $10.”

Young Benny was hooked. It was such an easy way to make money, he thought. He raised his stake to 50 cents and subsequently $1. But nothing came out of that.

“Within two weeks, my $15 earnings disappeared,” he said.

When his uncle found out that he had been playing chap ji kee, he scolded Benny.

Benny, his wife Anne, with their daughter and granddaughter, who is 7.

“Do you know that this is a scam?” his uncle said. He told Benny that the people running the game pick the winner from the entry that has the smallest bet.

On his uncle’s advice, Benny “graduated from two digits to buying 4D” when he was 12 years old.

When he was 15, that same uncle taught him to bet on horses.

Learning English

At age 13, Benny dropped out of school.

“My mum tied me up and beat me for two days to get me to go back to school,” said Benny. “But I refused. I did not like schooling.

“I also thought I was smarter than the teacher,” he said. He recalled how he had corrected his teacher’s pronunciation of the word “alias”. Furious, the teacher had thrown a book at him.

“My mum tied me up and beat me for two days to get me to go back to school. But I refused.”

Benny then went to work for his father who had an import business selling liquor and baking ingredients.

“I couldn’t do anything except odd jobs because my father thought I was useless,” he recalled.

Benny stole money from his father to gamble and also to buy char kway teow. “A plate cost 20 cents.”

Coming from a Hokkien-speaking family, he soon realised he needed to brush up on his English to get a decent-paying job.

“I came across an English language correspondence course advertised in The Straits Times. It featured people who had made it in life without a formal education because of their knowledge of English,” he said.

Benny couldn’t afford the course fee of $60 and his dad did not want to finance him.

“So I went to a secondhand bookstore on Bras Basah Road. I bought an English dictionary and grammar books to study on my own.”

Salesman in the making

When he was 20, Benny found a job as a deckhand on a suction dredger working on Singapore’s land reclamation. It was dangerous work that paid very well.

“In the 1960s, a clerk earned $80. I was paid $160 every two weeks,” said Benny, who was unable to get other work because he lacked paper qualifications.

He then moved on to a multi-level marketing job which turned out to be a scam. Benny lost half of his mum’s savings to it.

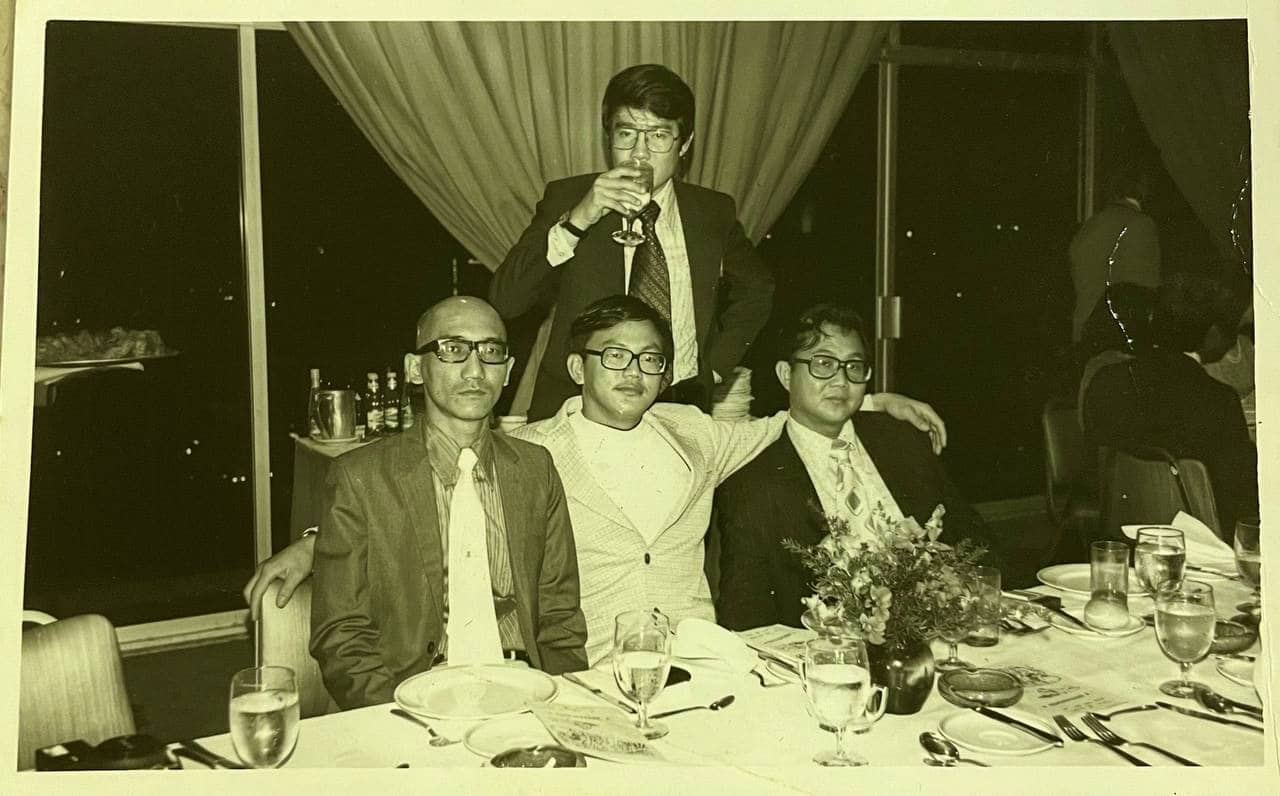

Benny (seated, centre) with friends on holiday. He was an insurance agent at that time.

But thanks to his good command of English, he eventually got a job writing letters for a textile merchant in High Street.

It was here that his life would change.

“One day, an agent came to sell insurance to my boss. I offered her coffee and we became friends,” said Benny.

This agent and her manager convinced Benny, then 21, to give selling insurance a try.

“I came into insurance reluctantly. I never thought I would make a good salesman,” admitted Benny.

Hooked on casinos

Under his manager’s mentorship, Benny gained a foothold in the challenging insurance business. The industry was then in its infancy in Singapore.

However, his mentor did not succeed in getting Benny to give up gambling – and often had to bail Benny out of debt.

Despite Benny’s addiction, his mentor kept on backing him.

“My boss saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself,” said Benny. “Also, he saw me teaching my colleagues about the business, helping the less fortunate ones who were struggling.”

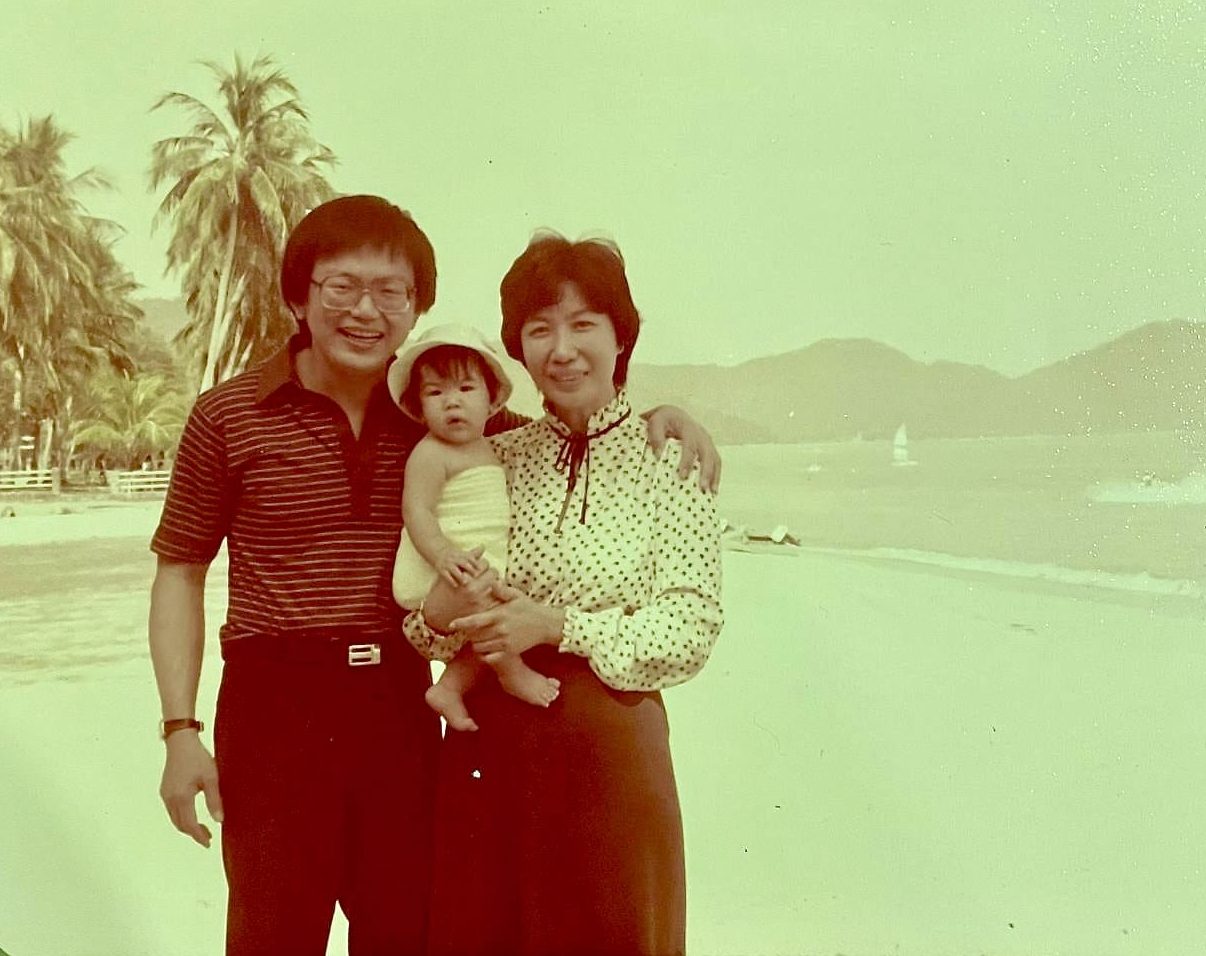

Anne was working as a cashier in a carpark when Benny met her. “I forgot to pay my season parking, and she helped me with it,” he said. They are pictured in Hong Kong in 1979 during a work convention Benny was attending.

Around that time, the casino at Genting Highlands had opened.

“When I lost at the gambling table, I sold my stocks. What I made in the stock market, I lost at the gambling table.”

Benny made a beeline there, and later to casinos in the region and beyond – Tasmania (at that time, the only casino in Australia), London and Las Vegas.

Encouraged by a client, Benny also started learning about the stock market. He would make huge returns on his investments that further fed his gambling addiction.

“When I lost at the gambling table, I would sell my stocks. What I made in the stock market, I lost at the gambling table,” he said.

“I didn’t know how to walk away when I was winning.

“If you gave me $2,000, I had to lose that $2,000 before I stopped.”

Six-figure losses

In early 1975, Benny lost a six-figure sum – the equivalent of two landed properties at that time – over 10 days by making a rash gamble on the stock market.

It put a big dent in his wedding plans: He had saved enough for his wedding dinner, but he did not have enough money to buy the diamond ring he had promised his bride.

In the first five years of their marriage, Anne’s allowance was often delayed because of her husband’s gambling losses.

Three friends lent him a total of almost $30,000, which saved him from going bankrupt.

To keep his promise of repaying them within three years, Benny worked doubly hard in the insurance business, emerging as one of its top agents.

Three friends lent him a total of almost $30,000, which saved him from going bankrupt.

“I believe in keeping my word,” Benny explained. “If you want a good reputation in business, you don’t promise something you can’t deliver.”

But whenever Benny was flush with money, he would return to the gambling table all over again.

Things finally came to a head in February 1980 on a junket to Jakarta.

“I brought $4,000, and that night I won $6,000. But then I lost both. The junket organiser kept throwing chips at me until I lost another $30,000.

“When I came back to Singapore, I had to sell my beautiful 2,200 sq ft apartment to pay for my gambling losses. For two years, I had to rent two rooms in a five-room HDB flat in Bukit Ho Swee to live in.”

Ever loyal, his wife Anne didn’t leave him.

Quitting mahjong

Soon after, Benny left for a conference in the US.

When he returned to Singapore, Anne told him the unthinkable: She had stopped playing mahjong, an activity she deeply loved.

“My client had a countenance that I admired. I was totally the opposite – easily agitated, easily angered.”

Her mahjong kakis (friends) had started quarrelling during a game, and she stopped playing with them. The same thing happened with another group.

With time on her hands, Anne called up the wife of Benny’s new client whom the couple had befriended. She asked to go to church with them.

“My client had a countenance that I admired,” recalled Benny of this man. “He was very calm, very cool and collected even though his office was bustling.

“I was totally the opposite – easily agitated, easily angered, and very proud of my achievements.”

The client shared with Anne and Benny how he had given up gambling after becoming a Christian. Benny was surprised by his story. The man did not look like a gambler to him.

“If you die right now, where will you go?”

Anne persuaded Benny to go along to church with her.

“I didn’t realise that God’s spirit had touched me. But I knew that something good had happened to me.”

He went for five weeks. He didn’t realise it then, but every week, the preacher had said the same thing: “If you were to die in your chair right now, where will you go?”

On the fifth Sunday, Benny responded to the preacher’s call and went down to the front of the hall.

“As I invited Jesus into my life, my tears couldn’t stop flowing. I didn’t know why I was crying,” he said.

“I felt a weight lifted from me. I felt so light – like a different person.

“When I walked back to my seat, I didn’t realise that I had become a Christian that morning.

Benny and Anne accepted Jesus into their lives in mid 1980. Two years later, they were blessed with a baby girl.

“I didn’t realise that God’s spirit had touched me. But I knew that something good had happened to me.”

“I’m not playing anymore”

A few weeks later, Benny was invited to a buffet at a friend’s home.

“Buffets were actually a cover up for the gambling,” he explained. “Usually I was the one who cut short the eating and asked for the cards. But that night, I didn’t.”

At around 10pm, Benny’s friends began to watch him with curiosity.

“Gambling was a habit I knew I had to give up, but I could not do so by own effort.”

“I finally said to them, ‘I’m not playing anymore.’”

Benny realised that his urge to gamble – an addiction that had plagued him for over two decades – had miraculously disappeared. For good.

“My friends asked, ‘Is there anything wrong with you?’

“I replied, ‘No, something very right happened to me. I’ll tell you one day.’”

Benny knew that, somehow, “God had taken away my addiction and that I was finally free of it.

“Before this, gambling was a habit I knew I had to give up, but I could not do so by own effort.”

Childhood memory

This incident reminded Benny of something that had happened in his childhood some 63 years earlier.

He was leaving school when he saw a few boys walking towards a church next door.

“Entrance exams coming, you don’t want to pray?” they asked him, referring to their equivalent of the Primary School Leaving Examinations.

“I knew this was something out of the ordinary: How could I pass when I hardly studied?”

Benny followed the boys into the church. It was the first time he had been in one.

“I was not a believer. I copied what the boys did. They didn’t pray verbally. They said their prayers in the heart. I did the same.”

From religious studies in school, Benny had learned that God was omnipresent and omniscient. So he prayed: “God, I can’t bluff you. I didn’t study at all. But I want to pass. The next few days, I will study.”

He did indeed pass – and was promoted to a better school.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he recalled. “My mum was so surprised. She had even told the neighbours, ‘My son sure fail.’ My classmates couldn’t understand how I passed.

“I knew this was something out of the ordinary: How could I pass when I hardly studied?

“In my heart, I knew it must be God. It cannot be me,” he said. “This was the first miracle I experienced even though I was not a believer.”

Financial freedom

After giving his life to Jesus, Benny asked God to restore his life.

To his delight, God answered beyond what he imagined.

“I closed probably one of the biggest deals in town, and the income allowed me to buy a house with a small loan,” he said.

“It’s not the amount in one’s bank account that gives security. It’s knowing that God is the source of everything.”

As he began to pray for guidance, he also saw how his clients needed more detailed financial advice than simply being sold life insurance.

And so, in 1990, after 23 years in the insurance industry, Benny, 44, left behind his six-figure payouts to set up his own company, Life Planning Associates. It was the most difficult decision he had ever made.

Today, he is seen as the pioneer of fee-based advisory for personal and business financial planning in Singapore.

“Given that I only had Primary 6 education, I consider this no less than a miracle,” said Benny, who describes himself as a “God-made” man, rather than a “self-made” man.

Benny has since retired and sold off his share in Life Planning Associates. Since 2018, he has been doing pro-bono work and volunteers with non-profit organisations. He is a committee member at Eagles Mediation and Counselling Centre.

As Benny began reading and growing in God’s word, he discovered freedom from worrying about his finances.

“True financial freedom is only possible when God is in the picture.

“It’s not the amount in one’s bank account that gives security. It’s knowing that God is the source of everything you have and can have, and trusting that He will provide for you,” said Benny.

“We don’t really own what we have. We are only stewards. God is the real owner who gives us the chance to be generous towards others.”

This story first appeared in Stories of Hope.

RELATED STORIES:

“God is bigger than chilli padi!”: How the Unlabelled Run is transforming lives

“The devil came to kill, steal and destroy but God restored my life”: Actor Li Nanxing

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light