Finding a way forward: An Asian mum in America reflects on racism and faith

Mindy Wang // July 11, 2021, 11:27 pm

"Thanks to my experience of racism in America, I have gained a new understanding of what my minority acquaintances must have been going through their entire lives in Singapore," says Mindy Wang (standing, fourth from right), who moved to the US when she was in high school. All photos courtesy of Mindy Wang.

Somewhere around the turn of the millennium, I found myself in an American middle school classroom. One day as I was doodling in study hall, Jay (not his real name) started sniggering behind my back.

“Whatchu drawing over there? Hey, I’m talking to you. Ecstasy? Do you do drugs?”

“Shut up, Jay.”

Mr Roberts (not his real name) walks over and tells me to be quiet.

I replied: “I just told Jay to stop bothering me.”

“Well you have to be quiet in study hall.” (Why just me, and not Jay too?)

Jay doesn’t stop. I get annoyed and we start arguing. Mr Roberts comes back around and asks me what’s the problem. (Again, why just me?)

Jay pipes up: “Mr Roberts, she’s talking about drugs to us here. Look what she drew on her paper.”

In the US, I was no longer a part of the majority race and with that vanished intangible privileges I had enjoyed in Singapore.

Mr Roberts takes a look at my calligraphic doodle of the word “ecstasy” and promptly decides to send me to see the school counsellor.

Ironically, I felt more anger at Mr Roberts for not stopping Jay from disturbing me in the first place than I was at Jay for the false accusation. I just couldn’t accept the unfairness of the situation.

Over the years, I discovered that many people in authority would be much harsher on me than on those who matched their skin colour.

Even amongst my peers, racism often presented itself in subtle ways. Today, we call these behaviours “micro-aggressions”.

In the US, I was no longer a part of the majority race and with that vanished intangible privileges that I had previously enjoyed in Singapore. It was eye-opening, to say the least.

Am I safe?

Fast-forward to 2021 and my newsfeed was filled with articles, one after another, of unsuspecting Asians being assaulted in public. What concerned me most was that during these attacks, the bystander effect often seemed to be in full swing.

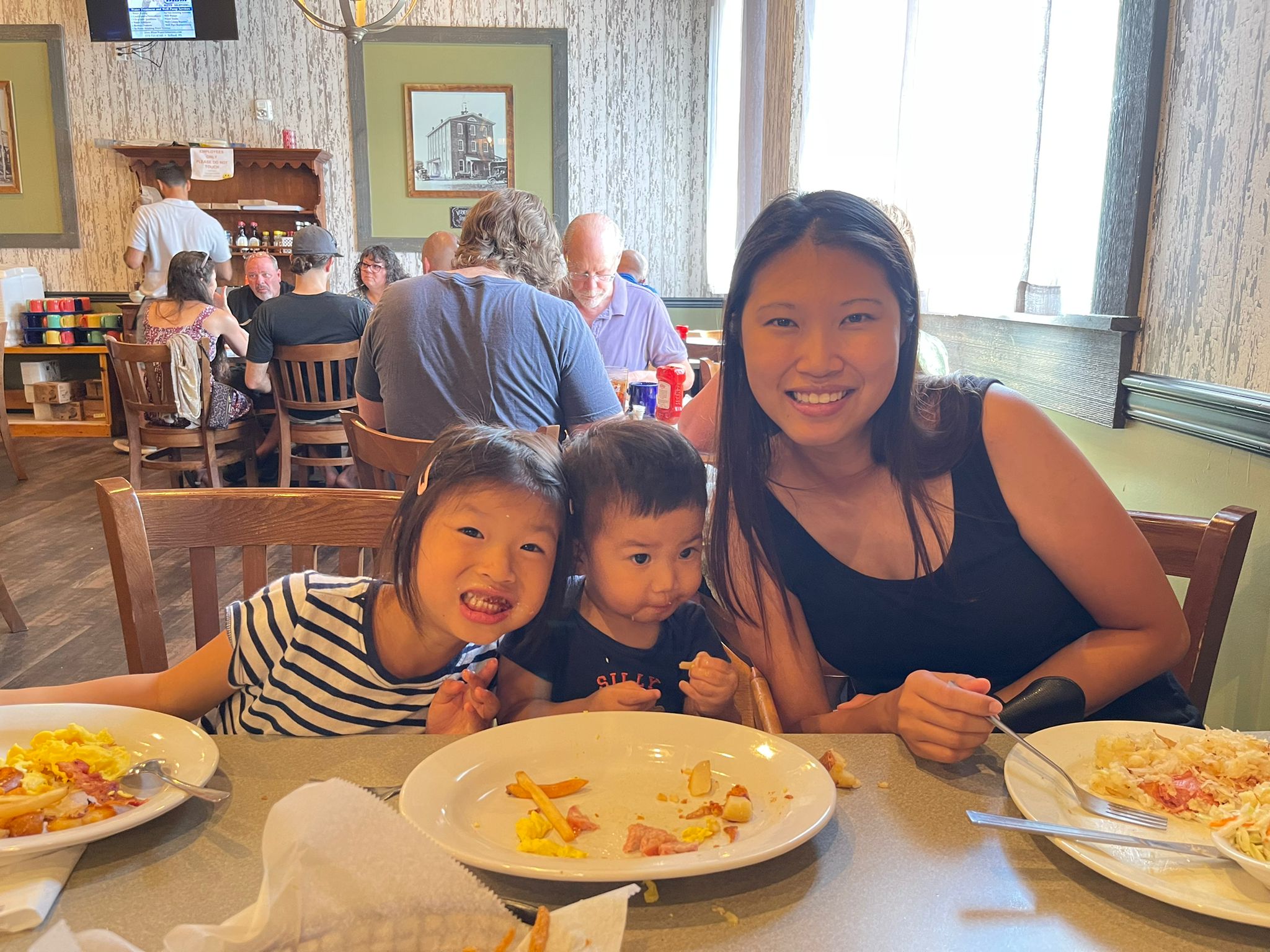

Mindy with Lauren and Declan, her two youngest children, having lunch this year. She often wonders how she will bring them up as Asians in America.

It worried me to realise that there were more violent racists walking around in society than I had previously imagined, and even more people who didn’t care.

Was every negative person out there just having a bad day, or were they angry at something my Asian-ness represented?

In March 2020, as my husband walked me into the labour and delivery unit, I couldn’t help but wonder: “Is there a racist working here, waiting to take revenge on a patient like myself? Am I safe?”

I repeatedly asked for an epidural but never got one. Was that a racist move, or not? I would never know.

So many of my everyday activities now became one big question mark.

When I took the kids to the playground, all masked up, I couldn’t tell if people were actually glaring at us or just looking serious. I couldn’t tell if moms at the playground were telling their kids not to play with my kids because they genuinely had to leave, or because we looked Asian. I couldn’t tell if people were driving aggressively because of how I looked or because they were chronic road-ragers.

Was every negative person out there just having a bad day, or were they angry at something my Asian-ness represented?

Brotherly love

On March 16, 2021, a widely-reported shooting at a spa in Atlanta that targeted Asian women brought the Stop Asian Hate (SAH) movement into even bigger limelight.

That week, as I strolled in the park with my children, we would meet an unusual number of strangers who were extra-friendly, striking up conversations and greeting us.

Mindy and her children (foreground) attending open-air church service last month as restrictions eased.

I knew they meant well, but the newfound attention made me uneasy too.

I knew they meant well, but the newfound attention made me uneasy too.

Amidst all the darkness and decay of these uncertain times, being a part of the local church community gave me much hope.

As I experienced brotherly love and fellowship between Christians of all cultural backgrounds, I was given a glimpse of heaven and respite from the “real world”.

In Revelations 7:9, the Bible speaks of “a great multitude that no one could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands.”

What a vision for the future! It is one worth clinging to when the current reality looks bleak.

Lessons for the next generation

I frequently mull over what the future would look like for my children. How should I teach them to navigate racism and unfair treatment, yet be filled with confidence in their own skin?

Revenge is not just wrong, it is an ineffective and imperfect form of justice.

First of all, I emphasise that our unique differences are to be celebrated. We all bring different gifts to the table. Wouldn’t it be boring if we all cooked the same food, spoke the same language, did the same things, looked exactly the same and wore the same clothes?

Secondly, what do we do when others treat us unfairly? Do we seek revenge?

Obviously, the Bible says not to do that. Not just because it is wrong, but also because it’s an ineffective and imperfect form of justice. In fact, Jesus tells us to do the very opposite of what our sinful instincts suggests: Love your enemies. Pray for those who persecute you (Matthew 5:44). Leave it to God to enact justice in His perfect and eternal way (Romans 12:19).

Feeling apologetic has to drive actual change to be useful.

Thirdly, I use painful experiences to generate compassion for others in the same or worse position.

Thanks to my experience of racism in America, I have gained a new understanding of what my minority acquaintances must have been going through their entire lives in Singapore.

I do not think it is enough that society feels sorry for those who suffer under racism. Feeling apologetic is an emotion, but it has to drive actual change to be useful.

Therefore, I now know it is just as important to speak up and take action in the face of injustice. It is not right that we should stay in our corner of comfort while ignoring the pain of others.

As people who believe Christ took the initiative to save us, we must also take the initiative to do better.

A new heaven, a new earth

It had been over a decade since Jay and I last spoke, but one day he randomly sent me a message asking if I would consider “hooking up”. He figured that, as an Asian woman, I would be entirely open to it.

I replied with an invite to church and told him that I would pray for him.

While initially offended at the rude message, I couldn’t help but notice how I now felt something new as well – sorrow – for a fellow soul who had not come to know Jesus yet.

When we forgive those who do not deserve to be forgiven, when we bear with one another in patience, when we walk in faith and not fear as we “Learn to do right; seek justice. Defend the oppressed. Take up the cause of the fatherless; plead the case of the widow” (Isaiah 1:17), what are we really doing?

Inadvertently, we are projecting a vision of a new heaven and a new earth. We are being the salt and light, slowing the decay of this dark age and pointing to Christ, who redeems us from all sin. This is how we can truly Stop Asian Hate, and hatred of every kind.

RELATED STORIES:

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light