A Novel pandemic: It isn’t just the virus that’s thrown us for a loop, says a doctor and church leader

Dr Lee Chung Horn // May 14, 2020, 7:31 pm

No misinformation is filtered out in an infodemic. The sheer volume of information is overwhelming, even for medical professionals, writes Dr Lee Chung Horn who went through the SARS crisis in 2003. Photo by Elijah O Donnell on Unsplash

The first thing that makes COVID-19 different from SARS is we now have social media.

Unlike 2003, we live in a hyper-accelerated information climate. The world has faced pandemics before and survived them, but we’ve never fought one poring over our screens before.

After the information flood-gates broke almost four months ago, there was no containing the water, no repairing the doors.

A difficult diagnosis

We didn’t have WhatsApp when SARS came. But WhatsApp now serves more than 2 billion people around the world.

When news of the coronavirus broke, my WhatsApp inbox began to swell to 400 messages a day. After two weeks, all the messages were about COVID-19.

If you also have accounts with Twitter, Instagram, Telegram or Facebook, your daily deposit probably swelled to the thousands.

This deluge is an infodemic, which the WHO has defined to be “an over-abundance of information that makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it”.

Medical people, who already live in a science information habitat, struggle to handle the sheer volume of information.

An infodemic does many things.

Firstly, medical people, who already live in a science information habitat, struggle to handle the sheer volume of information. The anxiety a lay person, with fewer day-to-day ties to unfamiliar medical information, feels would be considerably higher, even touching panic levels.

Doctors would know the medical definitions, but not an accounts executive, a housewife, or church worker. This is not being ungenerous, this is stating a fact.

If you don’t understand what the affix “novel” means, you won’t understand why making a diagnosis was so hard at the start.

“Novel” means the virus is brand-new, it’s not something scientists and virologists had studied extensively before. Because of its “novelty”, characterisation becomes the first step. We need to characterise the virus properly – and scientists now know that the 394-glutamine residue in the RBD region of the virus is recognised by a critical lysine-31 residue on the ACE2 receptor in human cells.

Social magnifier

The next step was to create ex nihilo – a test that would tell us if the virus was present in a person, or not present. We would want to know the accuracy of the test, its specificity and sensitivity.

To make things even harder, what is accepted as official, scientific truth at the start may shift over time.

A lay person would not understand this, and hence get distressed over what he may think is sloth or bungling.

When social media puts a magnifier on everything, when people are quick to make their own “expert” judgments, the opinions that shake the social media universe can feel like an earthquake, never mind that the instigating tremor was an unimportant, later-debunked hypothesis.

This is all behind us now, and we now have tests, all reliable, give and take minutiae that lay audiences should not have to understand.

We now have a tool of measurement.

When people are quick to make “expert” judgments, the opinions that shake the social media universe can feel like an earthquake.

Because it is an unmitigated flood, the second thing about an infodemic: It doesn’t filter misinformation. I heard many falsehoods.

For example, smoking kills the virus. Or drinking strong alcohol. Or that pets will give you the virus, so stay away from your aunt’s cat.

To make things even harder, what is accepted as official, scientific truth at the start may shift over time.

Because of the urgency, important scientific information is allowed to be shared as quickly as possible.

This removes the important filter of peer review, where findings are independently reviewed and fiercely interrogated by expert peers ploughing the same field.

WhatsApp fights

In early February, I got into my first WhatsApp fight.

Panic was rising in the country. Singaporeans started to count numbers every day, then they were sharing unverified information about places to avoid.

I dislike misinformation because it obstructs medical work. Every person values truth, but doctors are sticklers about medical truth because our stakes are not ordinary. Our stakes draw a line dividing health from illness, life from death.

After my fight, I realised that I was zealous, and lacking in compassion. Not every falsehood-monger is peddling fake data or silly cures. She may be a worried mom with school-going children, and science may not have been a subject she took in school.

Every person values truth, but doctors are sticklers about medical truth because our stakes are not ordinary.

We know many people reflexively share all the messages they receive. I don’t know if the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act, or “POFMA” has made a difference. We didn’t have “POFMA” at the time of SARS.

Every day, the doctors in the medical chat groups that I’m part of study a torrent of scientific studies, graphs and disease models. Some attend webinars and post summaries. Many wring their hands over political news. Several slyly trade information about the WHO.

An expert in our group who has expertise with the drug hydroxychloroquine, which is used for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, is still incessantly grilled about it by those who have never used it.

Some doctor friends were upset the circuit-breaker period (April 7 to June 1) was not imposed earlier. The doctors who didn’t agree kept quiet. You can identify the factions inside any group by the positions taken.

Always inevitably, you also have a silent group. The sentiment in the latter group is harder to parse – are these people silent because they are polite, unconvinced, or resigned?

Setting the bar in churches

In our church, people argued over whether or not they should be wearing masks. By February, the government had sent out advisories.

This is how science works. It shifts. This is not dishonesty, it is barefaced honesty.

Masks, at that time, were in short supply. This caused concern. But apart from the issue of scarcity, many ordinary church members have never worn a mask before.

They said it felt weird. Was it really necessary? Other people got angry and said: “If we’re not going to make people wear masks, I’m not coming to church.”

It was trying. Our church leaders worked to get the messaging right. We knew that sloppy messaging, or messaging that was discordant with what was coming from our national leaders sow seeds of polarisation. In the information age, trust is easily eroded in government, and church.

Not every church leader has training in public health or medicine. We want to make sure that our measures were not excessive or annoying. But excessive or annoying is a low bar.

Everybody had to pull together while standing in a fast-flowing river of fears and self-righteous opinions.

The correct bar to identify is: Are our measures genuinely effective, and not a vain display of work? Are thermometers important? What type? Are masks required? What is the true value of sanitisers? Are gloves needed? How do you tell Mr Goh he cannot enter the church, and should go home? Should Mrs Goh go home, too? But she has no fever. Do opened windows let the virus out, or in?

Many of our church leaders, even those with backgrounds in science and medicine, found the work stressful. Everybody had to pull together while standing in a fast-flowing river of fears and self-righteous opinions.

Some churches had to consult with ecclesial and denominational leadership; all had to abide by guidelines issued from ministries and government agencies.

Well, the word on masks has shifted in Singapore, as the pandemic epicentres later moved from China to Europe and to the US.

This is how science works. It shifts. Because they have been working, the best scientists may tell us that the first understanding they shared is now in need of adjusting. This is not dishonesty, it is barefaced honesty.

The crisis of coming home

On March 17, a government advisory (Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Education) was sent out, encouraging Singaporeans, especially students living overseas, to head home. There were leaks judging from the social media rumbles that started a week before.

More and more international airports were turning away even transiting aircraft. Sorry, no parking on our tarmac.

I was caught in this maelstrom because my wife and I have a son studying in Edinburgh. The women whom my wife was friends with were worried.

I am not plugged into Singapore’s diplomatic or education world. But I soon learned that the cries of “Bring your children home!” had set on fire parent groups.

Air travel, never a simple thing, was turning into a snarl. By this time, the travel industry had already plummeted in a deadly fall because people thought flying for seven hours anywhere was the height of foolishness. As the virus continued to spread, new lockdowns and travel bans sprang up each day, resulting in flight and connection disruptions.

Governments were now discussing whether they should protect their airports from becoming infected. More and more international airports were turning away even transiting aircraft. Sorry, no parking on our tarmac.

I don’t know how many of Singapore’s sons and daughters study overseas, or how many were away on internships and exchange programmes. But our students were understandably upset. The advisory had come out March 17, telling them to come home by March 20.

Whether it was London, Melbourne, or Japan, the advisory was felt personally. Every student had his own take on the crisis.

Whether it was Hertfordshire, Missouri, London, Melbourne, or Japan, the advisory was felt personally. Every student had his own take on the crisis. Some students argued that young people were relatively safe with the virus. Others said returning to Singapore could expose them to more danger than staying put overseas.

There were words with parents, of course. But what resolved disagreements between families and students, and pushed students through the skies was the progressive closure of many overseas universities.

Classes were suspended, exams cancelled, exchange programmes stopped.

“You are advised to return to your home country until we open again,” was a common guidance from overseas universities. We might remember that the return of Singaporean students later fuelled a short-lived rise in the number of infections in Singapore.

Reverting to default

Jesus spoke these words: “On that day, let the one who is on the housetop, with his goods in the house, not come down to take them away, and likewise let the one who is in the field not turn back.” (Luke 17:31)

Jesus was talking about the day of the Lord, a coming time when things will change. When the day arrives, there would not be time any more. In John’s Gospel, Jesus re-calibrates our thinking about time by telling us that it is still day, but night is coming “when no one can work”. (John 9:4)

Our unspoken assumption seems to be that we will, sooner or later, return to the world as we knew it.

Anxiously, many of us are working every day to forestall calamity, and protect our families. We are staying at home obediently, we are buying food and toilet paper, we are making sure our children take part in home-based lessons, we are protecting our seniors. These are the barricades we hope will save us from the night, the virus.

In all of this, our unspoken assumption seems to be that the world will survive COVID-19, that our strategies are, to a certain degree, effective; that we will, sooner or later, return to the world as we knew it.

Then, as we pick things up in our offices, communities, schools and churches, as we rebuild shattered livelihoods, we will see another day. Again, we will await the day of the Lord, when it will come.

Why do we take this position? Why do we reflexively think the crisis will surely end?

I think it is because the information age, with its admitted defects which we wisely try to keep away from, has still taught us to rest on modern, real-world data.

Indeed, no Christian, while he remains a member of a pluralistic world community, can faithfully jettison science, or make light of data. If the church does this, we won’t be able to have any useful conversations with anybody. We must walk on the bridges that truth, science and data build.

But this may not be good enough.

Shaking down mission and ministry

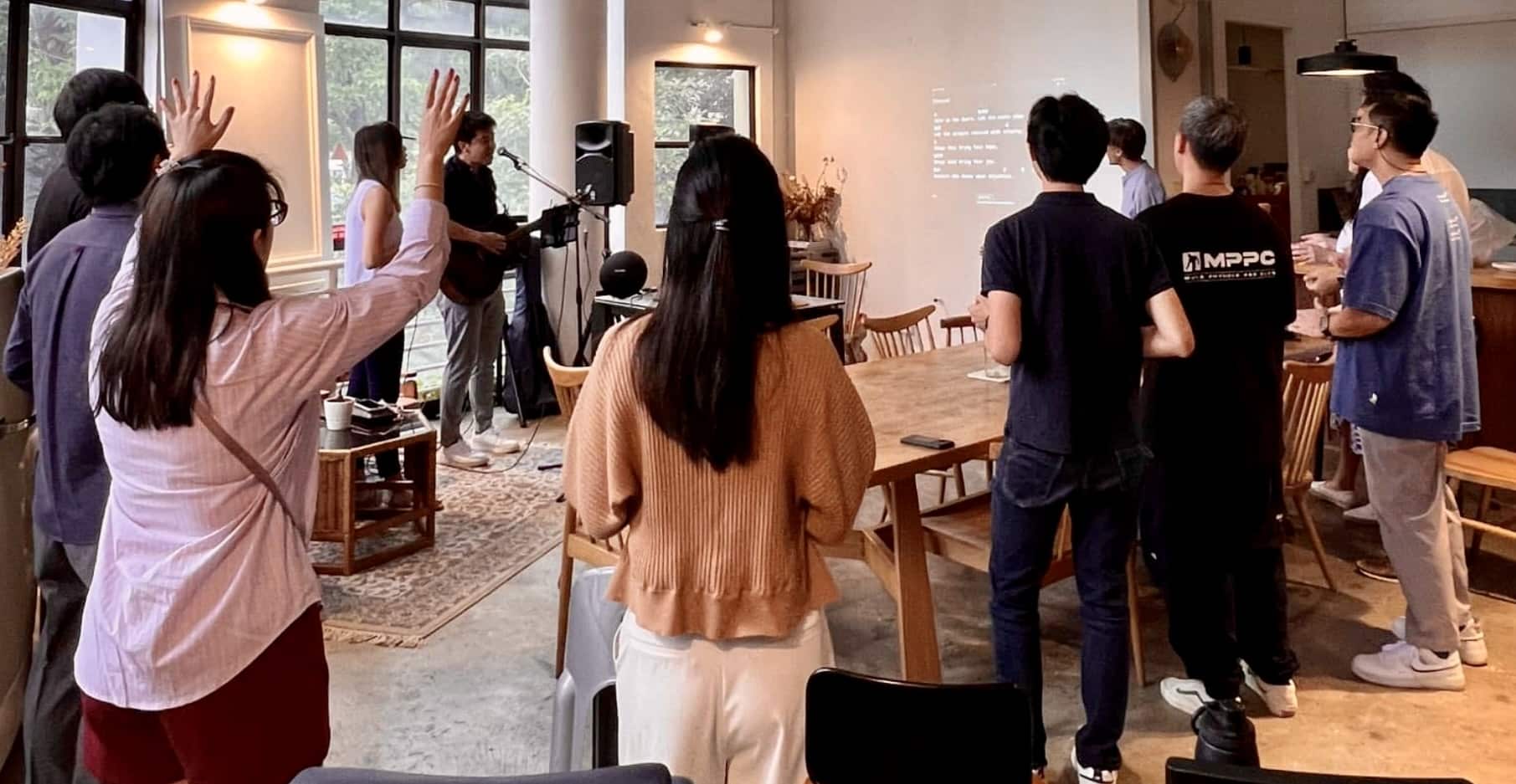

I think we need to appreciate that the empty churches we cannot now enter may have to change in ways we aren’t ready to countenance, if the upheaval ends. Perhaps recovery will be less of a problem for those of us in still-Christian Asia.

We need to appreciate that the empty churches we cannot now enter may have to change in ways we aren’t ready to countenance.

But a virus-ravaged, post-Christian Western Europe where churches are seldom full or flourishing will need to make brave, new plans to explain the idea of physical churches, among other things.

For now, we in Singapore may still tell our people that when the pandemic is over, and church doors reopened, it could still be like it was before – joyful worship, expectant faces and hopeful hearts.

A dear pilot friend from my church told me that the coronavirus calamity has grounded his flying. SIA has cut 96% of its operational capacity. One of our four airport terminals is now shuttered, and will remain closed for 18 months to save running costs. Despite the government’s relief packages, nearly all restaurants in our country have seen a 90% decline in sales.

He said: “This is a good time to observe Lent and reflect on spiritual things because we all have time now.”

He speaks wisely. We also often say people find God when they face tough times.

But is that latter statement just an easier line to make, than to declare that we will write our church budgets again, we will take everything through congregational approval again, not because giving has gone down but because post-coronavirus, our churches need to shake down mission and ministry, plan for the future, and not forget that we first need to feed and clothe our brother and our sister, and our neighbour?

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light