“If they tell you they want to die, it’s an opportunity to help”: Salt&Light Family Night panellists on suicide prevention

by Christine Leow // May 28, 2021, 6:03 pm

“We are very fond of giving advice," says Ps Chua Seng Lee. "But when we give advice, we engage the mind. In order for us to establish the right connection, there is a need for us to connect with their heart first." Photo by Marco Bianchetti on Unsplash.

It was clear from their deeply personal questions that their hearts were heavy.

On Tuesday (May 25), nearly 600 gathered on Zoom for Salt&Light Family Night’s discussion about suicide ideation in children and youths. Apart from Singaporeans, some joined from various parts of Malaysia and a few from as far as the Netherlands, the United States, Japan and Australia.

“My child attempted suicide four times. How can I help?”

Almost half (46%) had personally been impacted by suicide and the questions they posed told of the heartache and pain they have experienced.

“Sometimes, I wish I was dead but I won’t kill myself because I’m afraid. Should I seek help?”

“My child attempted suicide four times. How can I help?”

“How do I handle a teen who keeps threatening suicide because one parent committed suicide?”

Fielding the questions was a panel who has intimate knowledge of suicide ideation. Adjunct Associate Professor Daniel Fung is a veteran child psychiatrist and CEO of the Institute of Mental Health (IMH).

Pastor Chua Seng Lee, Deputy Senior Pastor at Bethesda Bedok-Tampines Church (BBTC), authored a book on overcoming depression among young people.

Alex Yeo is an Operation and Community Relation Manager with Caring for Life (CFL), an organisation that seeks to create supportive communities familiar with the early signs of suicide ideation. He had also struggled with suicide ideation.

These are some of the tips shared by the panel on how to help children and youths with suicide on their minds.

How do I talk to someone thinking about suicide?

1. Validate feelings

Yeo, who has lived experience with suicide ideation, talked about the need to begin with allowing the person to air his emotions.

“If the person says, ‘There is no purpose in life anymore’, the last thing he or she wants to hear is the statement, ‘No, you are wrong’.

“There is a need for us to connect with their heart first.”

“Or if they say, ‘I’m useless’, and then we straightaway rebuke and say, ‘No, you are not’.

“Instead, ask them, ‘Why do you feel you are useless? Can you tell me more? I would like to know how you feel, why you are having this pain. I care.’”

Added Ps Chua: “The technique is called validation. We need to validate their pain. We need to validate their experience.”

2. Connect with emotions

Ps Chua said: “We are very fond of giving advice. But when we give advice, we engage the mind. When the person comes to us, they are sharing their pain, their heart, their feelings with us.

“In order for us to establish the right connection, there is a need for us to connect with their heart first.

“Even if we don’t understand their feelings, it is okay to say things like, ‘What I am hearing is that you are feeling very wounded by what is going on.’

“Paraphrase the feeling so they can see your effort in connecting.”

Yeo agreed that relating to emotions is key.

“Say, ‘I have not been through the situation, but I really feel your pain.’ It is very important for a connection to be established.

“It’s like when the counsellor was speaking to me, a lot of it really came from the point where the counsellor says, ‘I can really see where your pain is coming from.’ That really helps.”

This validation of feelings is the beginning of empathy and trust-building.

Validation can be as simple as providing a comforting presence.

Said Yeo: “We keep hearing this buzzword ‘empathy’. In order to show empathy, you need to know where this person is coming from first and, therefore, there is a need to give them the space to share.

“We need to remember that there is a lot of pain in the person. If we give all the encouragement too soon, then the person might think, ‘But you don’t know what I’m going through.’

“Instead, let the person know you want to hear from him and that you are someone he can trust. Once that connection is established, you will be surprised how it might set a foundation so that he knows who to reach out to next time.”

Sometimes, validation can be as simple as providing a comforting presence. Ps Chua shared how his wife once sat in silence for two hours with a woman who had sought her out. The woman’s pain was so great that she simply could not talk about it.

It took two to three more of such sessions before the woman opened up to talk about her pain.

3. Encourage conversation

After connecting with the person, you can coax him to talk.

“There is a difference between asking ‘What’s wrong?’ and ‘What has happened?’ When you say, ‘What’s wrong?’ you are trying to assign blame, trying to find a cause. It may sound accusatory.

“Whereas if you ask, ‘What happened?’ you are showing care, showing interest, you are encouraging expression and talk.

In talking to someone about suicide, “I don’t think there is so much a taboo topic as how you say things”, pointed out Adj A/Prof Fung.

Is my child just seeking attention?

Take every mention of suicide seriously, urged all the panellists.

Said Adj A/Prof Fung; “When anyone says they want to kill themselves, it is important to listen.

“Seeking attention is usually very flippant. It is not asserted in a way that is serious.

“Someone who knows the child will know the difference.”

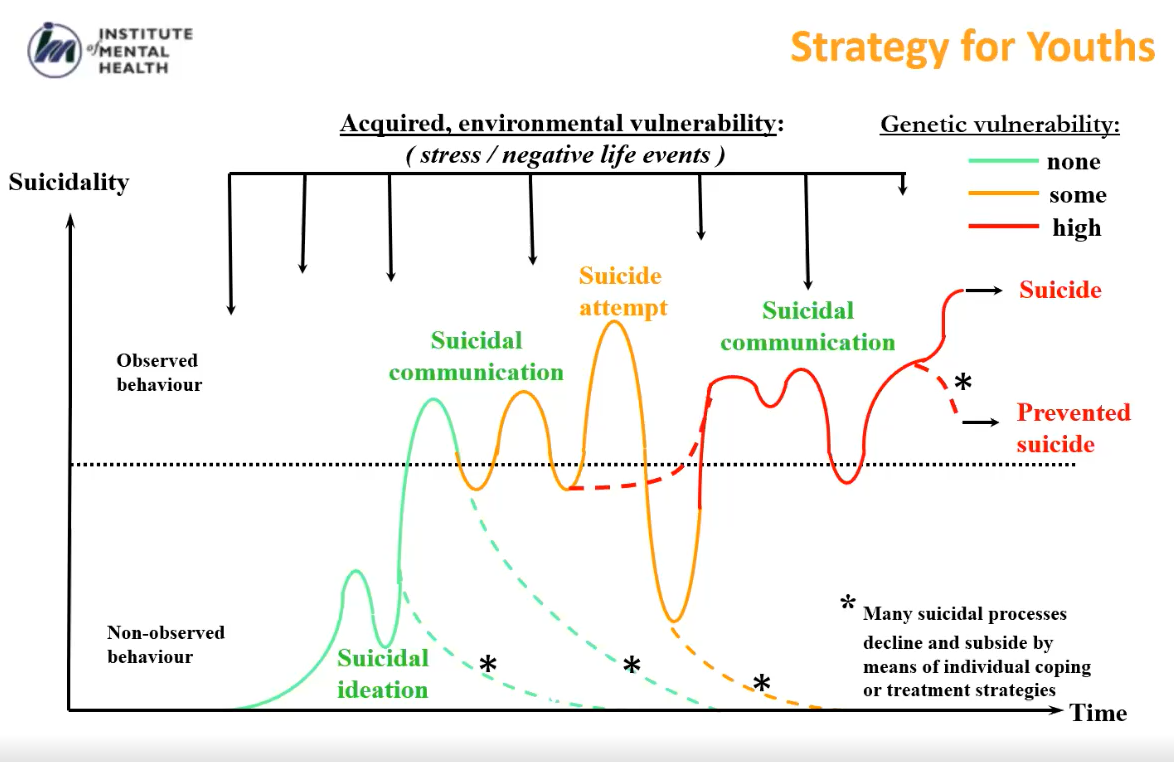

What is expressed is just part of suicidality. According to Adj A/Prof Fung, suicidality includes non-observed behaviour – suicide ideation – and observed behaviour, which comprises suicidal communication and suicide attempts.

Suicidality encompasses the observed as well as the unobserved behaviour. Acquired and environmental vulnerabilities as well as genetic propensities can have significance over whether ideation and communication escalate to attempts. Slide courtesy of Adj A/Prof Daniel Fung taken from Suicide an Unnecessary Death, 2nd Edition by Danuta Wasserman.

“There are many acquired and environmental vulnerabilities such as stress or negative life events, and genetic vulnerabilities that can result in suicide ideation and attempts.

“Communication can occur at various points. Communication in the earlier phases is harder to tell. Because there are no attempts, you might think they are ‘just saying it’. So, you don’t know whether to take it seriously.

“When anyone says they want to kill themselves, it is important to listen.”

“Once they start to attempt, it becomes worrying. You must take it very seriously because the prediction of suicide from an attempt is very high. It is the one thing that we can use to monitor suicide.”

Agreeing with Adj A/Prof Fung on the need to take every mention of suicide seriously, Ps Chua shared a story of a student who confided in his teacher that he had suicidal thoughts.

“The teacher didn’t take it seriously and the child died by suicide. One life lost is one life too many.

“There is a need for us to exercise patience especially knowing that young people are going through this period of a lot of emotional mood swings. There is a need for us to handle their cry for help seriously.

“For a child to say, ‘I am suicidal’, there must be some trigger. I’d rather we err on the side of being more careful than less careful.”

How should I respond if my child talks about suicide?

There are some positives when a child expresses his suicide ideation.

Explained Adj A/Prof Fung: “When suicidality comes out either in communication or attempts, that is already more overt. When it does come out, it also offers an opportunity for help.

“Sometimes, we get very worried when the child says, ‘I want to die.’ But his saying this is a good thing, because he is trying to share a feeling that he has that he doesn’t know how to deal with.

“You tend to react when you hear this kind of things. Don’t. Calm yourself and listen.”

“Very often, these communications should be seen as cries for help and we should be overt in trying to provide support and help because they asked.”

Once the channels of communication are open, engage.

Said Ps Chua: “Ask the child to tell you more. Ask, ‘What happened?’ We should not invalidate their feelings but be more inquisitive to find out more. What are the triggers? What are the problems they are facing?

“Assure them that we don’t judge them, ‘You have a safe space with me. The fact that you are willing to be vulnerable with me, I honour your vulnerability. I want to hear you out.’”

Added Adj A/Prof Fung: “Sit down and listen. It’s the hardest thing to do because you tend to react when you hear this kind of things. Don’t. Calm yourself and listen.

“Then, exercise good judgement and be level-headed. Process and listen and see what else you can do.

“If they come to you, that means you have a good relationship with them and that is an encouragement.”

How should I respond if I hear about my child’s vulnerability from someone else?

Adj A/Prof Fung urged parents to talk to their child about their suicide ideation even if their child did not approach them about it first.

“Collaborate with the person to learn how best to support your child through the journey.”

But, parents need to process their own responses before approaching their children, reminded Ps Chua.

“Talk to other parents. Find your support. Get yourself sorted out emotionally.

“We have to deal with our self-esteem, we have to deal with our own regrets, we have to deal with our self-blame. So, we need to sort out all our own emotions adequately first before we work out something for our child.”

Ps Chua also recommended that parents work with the person in whom their child has confided.

“Since the caring adult tells you, it means that the caring adult has a certain relationship with your child.

“You might want to learn to collaborate with the person to learn how best to support your child through the journey.”

Should I bring up the topic even if the youth does not mention it?

If you suspect someone is thinking of suicide, you should always broach the topic, said Adj A/Prof Fung.

As a caring, responsible adult, probably the best question to ask is: “Have you been thinking about killing yourself?”

“There is a need for parents to be open about talking about it.”

“It is a myth that, if you ask a suicidal individual this, it will drive him to it. Far from it. If you ask and he tells you about it, it is a bit more proactive.”

Even if there is no suspicion of suicide ideation, Adj A/Prof Fung still advocates talking about suicide. “Don’t avoid, talk about it”, he said, as it helps to remove the stigma that has long been associated with the issue.

“There is a need for parents to be open about talking about it. You have many opportunities. Newspapers do report a lot more on it now.

“Many of us do have experiences (with suicide ideation). It is worth discussing. It could be part of a conversation with your own children. This is general preventive work to talk to your children early on.”

How do I talk to someone who has attempted suicide?

The panellists were careful to make a distinction between providing support and giving help.

Said Yeo: “You need to be aware of your limitations. Are you able to do things like counselling, trauma care? Know your role. You are there to show love and continue to have the connection.

“We are there to give the person the safe space to open up to you.”

“Hopefully, as a follow up, you can have a partnership with a professional to continue to support this person.”

Then count the victories, however little. Even if the person does not open up, if you had the opportunity to “spend time with the person, show presence and care”, consider it a win.

“We are not there to impose our personal values and thoughts. We are not there to correct,” he said.

“We are there to give the person the safe space to open up to you and from there to see where the conversation leads.

“If the person is not comfortable with the topic, he will tell you.”

What if the person I am helping swears me to confidentiality?

Establishing safety protocols is very important, maintained Ps Chua.

“In my church, we define confidentiality as ‘those who need to know must know’. We will not intentionally tell everybody.

“But when the issue is beyond me, I have the freedom to escalate to the next level.”

Adj A/Prof Fung agreed that wisdom must prevail.

“When there is a safety issue and risks, it is best to not be completely confidential.

“It is what I consider one of the exceptions to confidentiality.”

This is the first part of a 2-part report on Salt&Light Family Night’s discussion on suicide ideation. Look out for Part 2 soon.

Where to get help

Hotlines:

- SOS 24-hour hotline: 1-800-221-444

- Care Corner Counselling Centre: 6353-1180

- Care Corner Parenting Support: 6235-4705

- IMH Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222 (24-hours)

Counselling:

- Care & Counselling Centre

- Email: [email protected]

- Focus on the Family Singapore

- Grace Counselling Centre

- Wesley Counselling

Call Caroline Ong for an appointment: 6837-9214. (Monday-Friday, 9am-6pm) - Haven Counselling Centre: 6559-1528 or email: [email protected]

- Bethel Family Life & Counselling: 6741-2741 (Ps Jean Ong)

Mental Health Directory:

RELATED STORIES:

Will talking about suicide make it happen? 7 myths about suicide debunked

Unprecedented suicide rate among S’pore’s aged: Are we failing our elderly?

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light