What I didn’t know when my mother died by suicide: 7 tips to help suicide survivors cope

On World Suicide Prevention Day today, Salt&Light recognises all who journey with those struggling with suicide.

by Christine Leow // September 9, 2021, 6:42 pm

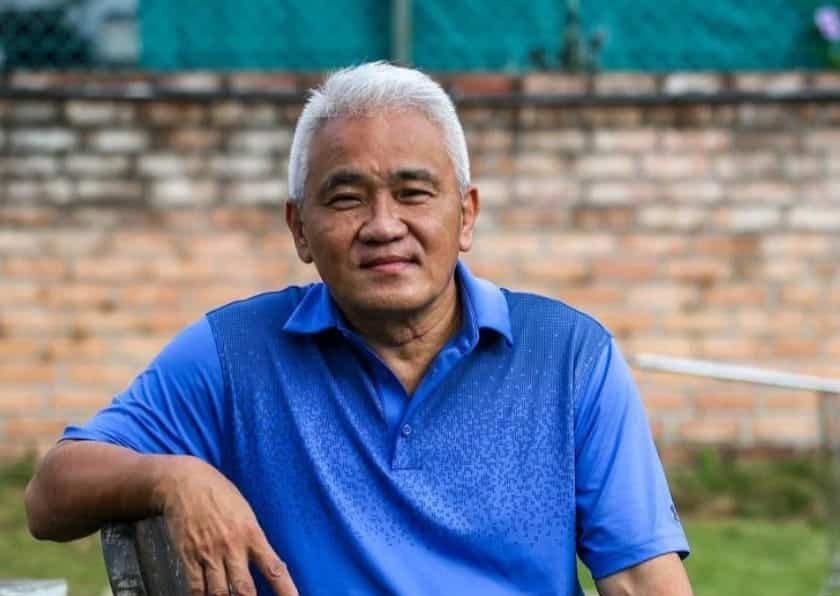

Last year, 154 seniors died by suicide, the highest number to do so nearly two decades. Each has a story of sorrow and suffering, each left behind survivors. This is my suicide survivor story. Image by Shameer Pk from Pixabay.

Trigger warning: This story contains material about suicide that some may find distressing.

On a blindingly bright Monday morning last year, less than two weeks before Christmas, my mother jumped 16 storeys to her death.

It’s the kind of thing you read about in the papers. It’s the kind of thing you hear happening to someone else. It’s not the kind of thing you think would happen to you. But it does. It did.

For every suicide, at least six suicide survivors are left behind. That is what I am now – a suicide survivor.

In that single act, my mum joined 153 other elderly who also took their own lives in 2020, contributing to a sobering statistic.

Last year, Singapore saw not only the highest number of suicides, an eight-year high, but also the highest number of elderly suicides. Not since 1991 has the nation seen that many seniors die by their own hand. It was a 26% increase.

Altogether 154 elders lost their lives to suicide. But many more felt the loss. According to the Samaritans of Singapore (SOS), for every suicide, at least six suicide survivors are left behind.

That is what I am now – a suicide survivor.

Down the dark road

When SOS released the numbers in July, the cause was attributed to the pandemic. That may have been the case for other seniors who died by suicide. That was not the case for my mum.

My mum cracked under the pressure of caring for my dad.

In June last year, Dad fell down in the toilet, hitting his head against the cistern. There was blood everywhere. Mum panicked.

Cleaning up after every leak drove my mother to despair and then to madness.

I got a frantic phone call.

We called for an ambulance and Dad was sent to the A&E. Miraculously, there was no concussion, no broken bones. Dad didn’t even need stitches. But he was hospitalised. The doctors were worried about the reason for the fall.

Two weeks and many tests later, Dad was discharged with a dozen or more pills and a devastating diagnosis: He had dementia and Parkinson’s Disease. Either may have contributed to the fall.

That was the beginning of the end. For Mum.

My dad came home dependent on diapers. Worse still, his diapers would leak for reasons no one could fathom. Nurses in the hospital I consulted, the private nurse I hired to troubleshoot, other caregivers I spoke to – everyone was baffled.

Cleaning up after every leak drove my mother to despair and then to madness.

She would spend her days squatting in a corner, wailing and pulling out her own hair.

She had always been a clean freak. Growing up, I had to wipe down my library books before I could read them because “there are germs”. So, this was her private hell.

Within six weeks, Mum had shrunk to 35kg. She couldn’t eat, couldn’t sleep, couldn’t move her bowels. She stopped functioning. The woman who once bustled about the house and cooked up a storm lost the ability to even heat up food.

One day, I found her naked in the bathroom, bone dry. She looked pitifully at me and said: “I don’t know how to bathe.”

She would spend her days squatting in a corner, wailing and pulling out her own hair.

One night, she called me at 2am and told me the police were going to arrest her because her house was in a mess.

Blow upon blow

As I tell you my story, I hear the questions: “Why didn’t you do anything? Didn’t you know something was seriously wrong?”

We did the usual – kindly advice, prayers, Bible verses. My mum, a Christian for 25 years, batted each away.

Every attempt at practical help was met with horror.

She didn’t want a washing machine. She refused to even let us buy her a mop, determined to clean the floors as she had done for five decades – on all fours with a rag.

One of her greatest fears was to suffer poor health. Now, fear had become reality.

When told we would hire a maid for her, she replied: “Then, I will swallow poison and kill myself.”

I should have taken that as a warning sign. I didn’t. By then, I was busy doing what she used to do in her own home – the cleaning, the cooking, the care of her husband.

Between Dad’s discharge and Mum’s descent were just two short months.

In mid-August, we finally convinced her to be hospitalised. By then, she had become so constipated, she had little choice.

She was diagnosed with situational depression and severe anxiety. But that was not the worst.

Doctors also discovered she had Stage 1 breast cancer, pre-diabetes and an eye condition associated with age.

With a fractured psyche and no medication, it was all too much for her to bear.

Mum had always been a fretful person. One of her greatest fears was to suffer poor health. Now, fear had become reality.

In truth, the reality was really not that grim.

Mum went through a mastectomy and was put on hormonal therapy. She would very likely have survived the five-year mark and beyond. The pre-diabetes and eye condition were minor and would have been under control with medication.

But with a fractured psyche and no medication – Mum threw away all her anti-psychotic medicine soon after she was discharged – it was all too much for her to bear.

On the morning that I was due to take her for an eye check-up, she jumped from one of her bedroom windows.

“How are you feeling?”

My last words to her were: “Don’t be a child, mum. I’ll pick you up tomorrow for the appointment.”

Imagine that. It wasn’t “I love you”. It wasn’t “Good-bye”. It wasn’t even kind.

The few friends I told about her passing the day she died – my best friends, my editor – asked with great gentleness: “How are you feeling?”

I couldn’t sort it out then. I have sorted it out since. This was how I felt, how I feel.

1. Relief

As awful and unfilial as it sounds, I was relieved.

After Mum was discharged from the hospital, she lived with me. I didn’t think she could take going home to my ailing father, especially since I had hired a maid for them while she was gone.

I was bracing myself for another psychotic break.

In the weeks before she passed away, she asked to go home. There, she became increasingly paranoid.

“The maid is angry with me,” she confided one day.

On another occasion: “I think the maid hates me.”

Finally, she became convinced the maid was plotting her demise. No amount of counselling or reasoning helped.

Every conversation ended in frustration on both her part and mine. I was bracing myself for another psychotic break, another round of hospitalisation.

When she died, a part of me relaxed a little.

2. Guilt

But a bigger part of me felt deep guilt for feeling relieved.

A bigger part of me felt deep guilt for feeling relieved.

She was my mum. She had raised me and helped raise my children. I should have been ready to dedicate the rest of my life to caring for her. Why had I been so impatient? Why hadn’t I been kinder?

In the months before she passed away, she had lived with me. Even when she moved back to her home, we had spoken to each other almost every day. Why had I not seen the warning signs?

Then came the “if onlys”. If only I had not let her go back home. If only I had assured her more. If only I had been nicer to her. If only I had taken her complaints more seriously – she had expressed a desire to escape it all and had talked about moving out.

3. Anger

Mum died without a will but everything was in her name – the flat, every bill, their savings.

Being the only child left in Singapore – my sister lives abroad – I was left to manage her assets. At times, I was angry with her for leaving me with a mess that my aversion to all things administrative made all the more difficult to manage.

She died without giving us a chance to tell her how much she meant to us.

I was angry at her seemingly selfish act.

Mum left without giving me a chance to say good-bye or make right our relationship. She left without seeing my children, whom she had raised from birth, one last time.

She was a month shy of seeing my sister and her child. They had planned to visit because my sister had been worried about both Mum and Dad.

In my darkest moments, I rued the fact that we didn’t mean enough for her to stay. She died without giving us a chance to tell her how much she meant to us.

4. Shame

I was ashamed that my mum died the way she did.

That shame also prevented me from celebrating her life, so dark was the stain of suicide.

It was as if I could not provide her love or reason enough to stay. It was as if she had not enough resilience or fortitude to fight for her own life. It was as if our faith in God was somehow weaker, of poorer quality.

Many people asked how my mother passed away. Few people, until now, got the truth. I was ashamed of her, for her.

To be perfectly honest, that shame also prevented me from celebrating her life, so dark was the stain of suicide.

5. Regret

In the days, weeks and months after she passed, I looked at every little old lady at the market or hawker centre and thought about how mum was missing out.

When my sister and niece eventually came to spend three weeks with us, I mourned the fact that she never got to be with them.

“Mum would have liked this …” was something my sister and I said often to each other.

6. Grief

I have loved words all my life.

When my mum died, she forever deleted one word from my vocabulary – Mummy.

When my mum died, she forever deleted one word from my vocabulary – Mummy.

Never would I ever have the chance to say that out loud to anyone anymore. I grieve.

When day fades into night, I still feel the urge to pick up the phone and call her.

That had been my practice all last year. I grieve.

7. Disbelief

To this day, I can’t believe that my mum killed herself. It was so contrary to the mum I knew.

The mum I knew wanted to squeeze every ounce out of life. She had FOMO (fear of missing out) before FOMO became part of the vernacular.

I can’t believe that my mum killed herself. It was so contrary to the mum I knew.

She didn’t like to sleep, was always on the move and loved to travel. She took supplements, ate healthily and kept active so she could live longer.

She was so afraid of death that she wouldn’t even buy life insurance because she was sure that would be her death sentence.

How could a woman like that die by suicide?

The reality, of course, is that the woman who eventually killed herself wasn’t my mum. Mental illness had robbed Mum of not only her ability to reason but also her personality.

True, she died by suicide. But it was mental illness that killed her.

Knowing that has, to some degree, removed the shame. It has also made me more empathetic towards and cognisant of mental illness and its effects.

8. Rinse and repeat

If life were simple, I would be feeling the emotions one at a time, and only once.

In reality, I often experience many of the emotions at once. Just when I think I had felt it all, some of the old emotions would return.

Here is where the comfort and redeeming grace of God have brought much solace. Much as I miss mum and grieve over the missed opportunities, I know that this sorrow is only for a season (Psalm 30:5). One day, we will meet again in a place where there will be no more tears, or mourning, or death (Revelation 21:4).

Tips for suicide survivors

Counsellor and grief recovery specialist Joan Swee, 62, says that all these emotions are common among suicide survivors whether they knew their loved one was suicidal or were surprised.

“Believers may feel disappointed and their faith may be shaken.”

The founder of Whispering Hope Singapore, a consultancy to walk people through all sorts of grief, adds: “Both groups of suicide survivors would likely experience a spinning wheel of unanswered questions, ‘Why did he or she choose to give up and exit on us all? Did our love count? Did we matter?’

“They are likely to rethink past conversations and interactions with their loved one, seeking answers or clues.

“Believers may feel disappointed and their faith may be shaken. ‘Why did God allow this to happen? How can a person who believes in God take his or her own life?’”

She offers tips to help suicide survivors cope:

1. Go ahead and grieve

It is normal to grieve our losses, Joan states.

“It is very important that suicide survivors be given permission to grieve. I cannot emphasise this enough.

“Permission to grieve means allowing the bereaved to cry, lament, shout and release all the raw emotions,” says Joan.

“Jesus himself wept over the death of Lazarus!”

Well-meaning people often talk about staying strong and moving on.

“This negates the awfulness and permanence of their loss. The person is suddenly gone and is never coming back. How can they go about life as if nothing has happened?”

Joan adds that grieving is “not incompatible with our belief in God” because Isaiah 61 talks about “mourning in Zion”, the Beatitudes (Matthew 5:1-12) talk about mourning and the Psalms are full of weeping and mourning.

“Jesus himself wept over the death of Lazarus!”

2. Talk it out

“It is important to give grief a voice and unload your emotions,” says Joan.

“Suicide survivors find that they are not able to talk about (the suicide) with the people in their social circles.

“Reach out with a warm heart and with big ears to hear the deep wounds of a fellow man.”

“Even within the family, the unanswered questions often mean that there is a lot of unresolved pain and grief.

“It feels easier just to avoid the topic and not to talk about it. But pain and grief that are suppressed will not go away just like that. The way to recover from grief is not to suppress it, but to acknowledge it and to release it.”

Here is where Joan encourages the church to look out for those who are hurting: “Reach out with a warm heart and with big ears to hear the deep wounds of a fellow man, and be a source of comfort and support.

“Journey with them, ‘walking a mile’ in their shoes, so we can empathise.”

3. Stay healthy

Take care of your health. Sleep, says Joan, because it helps mental health.

“Find healthy ways of releasing pain. Physical exercise like going to the gym, kick-boxing, jogging and other sports can help to release inexplicable emotional pain.”

4. Be informed

Read up on positive grieving because it “helps to normalise grief”.

“As you identify with the writer’s experiences, you will find assurance that ‘I’m not alone’ and ‘I’m not crazy’.”

5. Watch yourself

Suicide survivors are said to be more likely to harbour suicide ideation and are at greater risk of suicide themselves.

Knowing this can help you and those around you ensure that your grief does not evolve into something damaging.

6. Get help

‘Many suicide survivors may experience trauma, for example upon discovering the body of their loved one, and suffer from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and need to see a psychiatrist or psycho-therapist to be stabilised,” says Joan.

“Speak to someone who has bounced back from the loss.”

Within this eco-system of helping professions are grief coaches like Joan who help suicide survivors in grief recovery.

She explains: “A grief coach is familiar with the nature of grief and is experienced in journeying with someone through the tunnel of grief.

“It helps a great deal to speak to someone who has experienced great loss, and who has bounced back from the loss.”

7. Give yourself time

“Don’t hurry in your grieving process. There is no absolute time frame for grief,” says Joan.

“In the immediate months of loss, a grieving person may show all the symptoms of major depression, but clearly, the survivor is grieving deeply.

“But, it is important to make sure you do not slip into isolation, leading to suicide ideation.”

RELATED STORIES:

Unprecedented suicide rate among S’pore’s aged: Are we failing our elderly?

Journeying with the depressed and suicidal: Tips for “people helpers”

“To live is Christ, to die is gain”: A full-time church worker’s struggle with suicide

“To live is Christ, to die is gain”: A full-time church worker’s struggle with suicide

WHERE TO FIND HELP

Hotlines

- SOS 24-hour hotline: 1-800-221-444

- Care Corner Counselling Centre: 6353-1180

- IMH Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222 (24-hours)

Counselling

- Care & Counselling Centre

- Email: [email protected]

- Focus on the Family Singapore

- Grace Counselling Centre

- Wesley Counselling

Call Caroline Ong for an appointment: 6837-9214. (Monday-Friday, 9am-6pm) - Whispering Hope Singapore

- Haven Counselling Centre: 6559-1528 or email: [email protected]

- Bethel Family Life & Counselling: 6741-2741 (Ps Jean Ong)

Mental Health Directory

Mental Connect

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light