Addicted to drugs for 40 years, he had given up on any hope of change. Then this happened

by Gracia Lee // July 5, 2022, 2:25 pm

Jail time, a mental breakdown and an overdose could not spur Samuel Wong to kick his drug addiction for 40 years – until he met God in a garden. Photo courtesy of HCSA Highpoint.

Samuel Wong knows all too well the cycle of addiction so many drug abusers go through.

Since he took his first puff of marijuana at 13 years old, he has lived through four decades of desperately wanting to change, making good progress and plunging right back into the lifestyle he swore to keep away from.

Many had given up on him. Even he had given up on himself. Now 65, he told Salt&Light: “I would look at others who had changed and think, ‘No way I can be free like that. I cannot don’t smoke. I cannot don’t take drugs.'”

Cleaning blood off weapons

Growing up with an uncle who was one of the leaders of a gang, Samuel was exposed at an early age to the dark and violent underbelly of society.

“The shophouse that I stayed at in Balestier Road opened up into a lane where gangsters would fight and clash. We used the back of the shop to hold weaponry,” he recalled.

When he was in primary school, he was given the job of cleaning blood off the metal pipes that had been used in fights.

Born the fifth of seven children, Samuel grew up in a shophouse in Balestier Road and was exposed to gang activities at a young age. Photo courtesy of Samuel Wong.

But it was not this early exposure to gangsterism that introduced him to the world of drugs. Instead, it was the hippie culture that he came to be involved in when he entered secondary school.

“I was very adventurous, very curious. The hippie movement involved long hair, rock music, that kind of party lifestyle. I liked how that felt,” he said.

As the fifth of seven siblings who had always felt out of place in his family, Samuel also relished feeling a sense of belonging in the community.

Camping was a common activity in the lifestyle, and it was at one of these camps that he – then only in Secondary 1 – was offered a stick of marijuana to smoke.

“I still remember that day very clearly. It was a rainy day and we were under a big beach tent. I took my first puff and it spiralled into a realisation that I really loved the feeling,” he said.

Marijuana soon turned into methaqualone (MX) pills, which then turned into morphine. His family was too busy grappling to make ends meet and coping with the death of his father, who had passed away from illness when Samuel was 14, to notice, let alone guide him back onto the straight and narrow.

“No one asked me how I was doing. They just let me do what I wanted,” he said.

“They thought I was going to die”

While Samuel’s family did not keep the teenager accountable for his actions, the law eventually did.

Toward the end of his National Service, he failed a urine test and was sentenced to 18 months in the detention barracks, where he spent his 21st birthday.

It was the first time his choice to take drugs had any kind of consequence. Struggling with having his freedom stripped from him, he decided that he needed to change.

“I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t breathe. My face was black and blue.”

“But the desire to change was more because I didn’t want this life spent in prison. It wasn’t about the drugs – the drugs, I still liked – it was more about the cost I had to pay and the consequence I had to suffer,” he confessed.

He enrolled in Teen Challenge, a Christian programme, when he was released from the detention barracks. But it failed to keep him from the vice.

Over the next few decades he would find himself in and out of prison and the Drug Rehabilitation Centre (DRC) seven times, caught in the same pattern of wanting to change, only to cave right into the pull of drugs.

He recounted the time he had successfully weaned himself off drugs, cigarettes and alcohol for a season while staying in Christian halfway house, The Helping Hand.

But after an unhappy encounter with his supervisor, he turned immediately to drugs to cope with his feelings of resentment.

He suffered from a drug overdose that day and was rushed to the intensive care unit. “I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t breathe. My face was black and blue. I was choking, gargling. They thought I was going to die,” he recalled of his near-death experience.

When he regained consciousness in the hospital, his first emotion was not relief that he had survived but fear of being arrested.

Pulling out all his tubes, he escaped from the hospital. “That afternoon, I relapsed again,” he said.

Hearing voices

Looking back on his life now, Samuel believes it was a sense of loneliness and inferiority that had driven him repeatedly to drugs.

“I just didn’t feel at home in the real world. The drug world was more appealing than the actual world,” he said, adding that he also took sleeping pills and drank cough mixture to destress.

“This is your new life from now onwards. Live it.”

Things came to a head when his family kicked him out of his house. That was when he started hearing voices talking to him in his head. Paranoia stalked him wherever he went, to the point where he would start scolding strangers on the MRT.

“But I felt good because at least there was somebody to talk to. I was so lonely,” he said.

On one occasion, the voices in his head challenged him to break into a particular home in Flower Road. So he did, and even took a bath while the house owner was not home.

“When the owner came back, I quarrelled with him and started asking him what he was doing there,” Samuel recalled with amusement.

Despite being in and out of lock-up seven times, Samuel struggled to kick his drug addiction. Photo courtesy of Samuel Wong.

He was arrested and admitted to the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), where he was warded for the next six months. He was diagnosed with mild schizophrenia caused by body substance abuse.

“That was a really frightening experience. I thought my life was gone,” he said. But the voices slowly started disappearing and he was eventually cleared to be discharged.

He went for a six-month programme back at The Helping Hand, hoping to cleanse his system. “But when I came out, I went on a rampage again,” he said. “I felt stressed about life in general and felt I couldn’t function unless I was high.”

A breath of new life

Despite Samuel’s addiction, his eldest brother took him in and allowed Samuel to stay in his home, where their mother also lived. During this time Samuel continued meeting drug pushers outside his brother’s home and doing drugs in his toilet.

Breathing in the cool morning air, he realised that he had never felt so … free.

“I felt really sick and lousy about that. If people are bad to you, it’s okay because then you can blame them. But if people are good to you, you can’t blame them anymore. They gave me a house to stay, food to eat, a place to bathe. But I made their house a drug place,” he said.

Disgusted with himself, he enrolled in another halfway house, HCSA Highpoint, though he confessed that at that point, he had no real hope or expectation of change.

But the morning after he checked himself into Highpoint – June 17, 2011, he still remembers – something unexpected happened.

At the break of dawn, he woke up feeling strangely different. It was the first time in a long time he did not feel an ache or itch for drugs, alcohol or a cigarette puff.

Puzzled, he walked out of his dorm on the second floor and found himself looking out over a big green field. Breathing in the cool morning air, he realised that he had never felt so … free.

An overwhelming feeling of peace, forgiveness and newness washed over him. “I think that was when I met God. It was just like someone was telling me, ‘This is your new life from now onwards. Live it.'”

“If you are at a place where you really want to change … God can be your enabler.”

It was not the first time he had heard about the Christian God. During his time at Teen Challenge and his various stints at The Helping Hand, he had been introduced to this God who loved him, gave His life up for him and could make all things new (2 Corinthians 5:17).

But now he finally experienced it.

“I realised then that I would love to have this new life and that I was willing to do difficult things to live it,” said Samuel.

When asked what might have led to this divine encounter, he replied: “I always believed it was my mother’s prayers for me that made the biggest difference. It was not my faith, but her faith that God would do something.”

A band of brothers

The journey back to sobriety was indeed a tough one, but Samuel found a group of three friends at Highpoint who became instrumental in encouraging him to stay on the right path.

“Guilt can be very crippling. So those who have been forgiven much will love much.”

“They were ah bengs and ah sengs, but they were committed not to touch drugs and cigarettes. I bonded with them and felt safe and affirmed in their company,” he said.

It was this feeling of acceptance and security that had been so elusive in many of his past relationships, which led him to build walls around himself for fear of rejection.

But with this group, he was at ease. He knew he could be himself. He did not fear that they would leave or disregard him at the slightest offence.

Samuel also drew strength from his newfound faith in God. “If you are at a place where you really want to change and you’re willing to put in the effort to recover, God can be your enabler to give you the strength through the community of believers,” he said.

Samuel (left) is now a programme manager at HCSA Highpoint, the halfway house where he turned his life around after four decades of addiction. Photo courtesy of Samuel Wong.

Knowing that he had been forgiven for all the sins in his life, a sense of thankfulness also began to take root in his heart.

“Guilt can be very crippling. So those who have been forgiven much will love much. Every day I started to invest myself in doing good, in seeing who else my life can touch,” he said. “I started to see that there is a purpose in my life, that there is something bigger than myself.”

Never too late, never too old

Since he made the decision to change that June 17 morning, Samuel has not turned back. It has now been more than a decade.

Today, he is a programme manager at Highpoint as well as a recovery coach and trainer in the Singapore Prisons, where he journeys with other men through their addictions.

“I always wanted to be soccer player or a musician. But I realised based on my experience that actually my football sucks, my music is also not so good. But one thing I’m good at is that I’ve spent many years with drugs,” he said candidly.

Over the past ten years, he has worked hard for a diploma and a higher diploma in social work, and is now hoping to earn a Masters in Counselling “at the ripe old age of 65” so that he can be better equipped to help those in the throes of addiction.

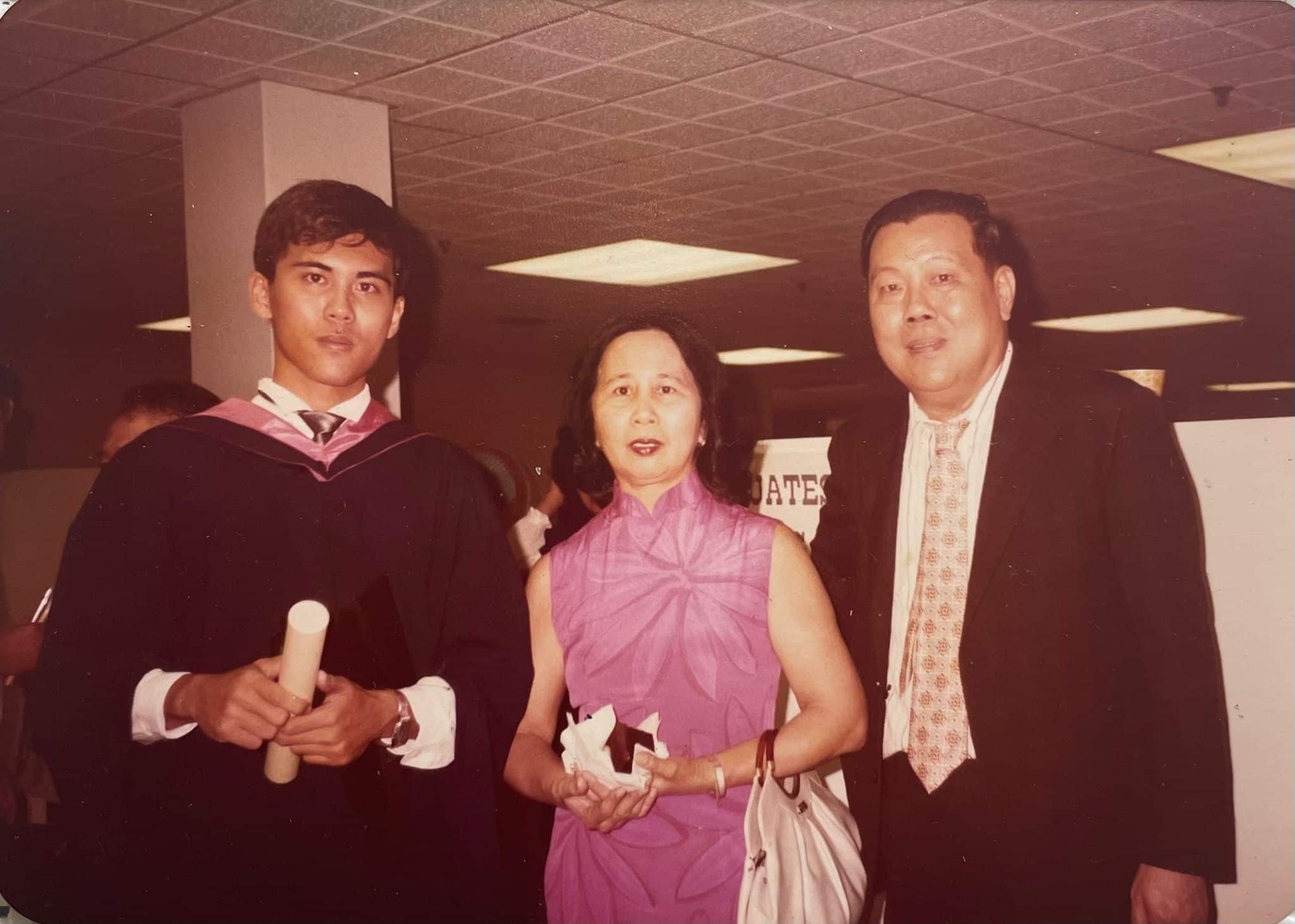

Samuel (left) at his graduation ceremony after receiving his higher diploma in social work from the Social Service Institute. Photo courtesy of Samuel Wong.

“I want to be an example not just for ex-offenders but also to inspire people that life doesn’t have to be over once you reach a certain age. It can still be meaningful.”

Even though it happened some 11 years ago, he can still remember the scent of the air and the feeling of freedom during his first morning at Highpoint – and it is this that spurs him on each day.

“That was the freedom of Christ. And this freedom is not for me to keep, it’s for me to live out,” he said.

“The grace of God can transform anyone who seeks His face – or even if they don’t seek His face. Why did God seek me out? I also don’t know. It’s all His grace.”

RELATED STORIES:

“God is bigger than chilli padi!”: How the Unlabelled Run is transforming lives

“God is bigger than chilli padi!”: How the Unlabelled Run is transforming lives

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light