God used her woundedness to heal others: Award-winning social worker Grace Koh

by Gemma Koh // May 5, 2020, 11:20 pm

Social workers are not superhuman, says Grace Koh. But "when our wounds cease to be a source of shame, and become a source of healing, we become wounded healers.” All photos courtesy of Grace Koh.

A toddler sucking on a rusty battery ignited Grace Koh’s fire for social work. The tot’s older sibling was playing with a tin can.

Then 17, Koh was in Cambodia, on a Girls’ Brigade service learning trip.

“God left me with nowhere to run and pretend poverty didn’t exist.”

Koh was struck by the plight of their mother.

“This mother did not mean to harm her children. But she was not educated about such dangers. And being poor meant she could not afford toys for her children,” recalls Koh, now 33.

The woman’s husband, the breadwinner, had abandoned the family. The woman was malnourished and ill. The only medication the village doctor could give her was panadol.

“That visit broke my heart in so many ways,” Koh told Salt&Light. “Here was a dedicated mother who, by no fault of her own, had poor access to proper healthcare, childcare, nutrition, social support and more.

“This was poverty and inequality staring me in the face. God left me with nowhere to run and pretend it didn’t exist.”

Koh would go on to study social work at the National University of Singapore.

New narratives

After graduating in 2010, Koh became a community social worker at a family service centre. She did early intervention work with preschool age kids, empowering their families to manage their psycho-social vulnerabilities, to ensure that they would be able to look after their children.

Subsequently, she joined a pioneering team in community child protection. She worked with families where there was abuse, suspected abuse and neglect.

The Singapore Association of Social Workers recognised Koh’s work. In December 2015, she received a Promising Social Worker Award from then Singapore President, Tony Tan.

Koh helps children with socio-emotional issues through play therapy at Good Pathways. She is also a freelance clinical supervisor of social workers from three different agencies.

Koh’s most challenging case involved helping to house a homeless, single, unwed mother and her infant. “Cases like this can fall right through the cracks, and require a lot of legwork and advocacy”.

“I still breathe a prayer for this family whenever I pass by on my bus rides.”

Through journeying with this family for four years, Grace “empowered this mother to navigate several shelters and many systems”.

“There were many moments I cried out to God to make a way where the doors were closed.”

Etched in her memory is one of her final visits when she saw mother and child happy in their “hard-fought rental flat”.

“As the mother shared excitedly about her plans for the future, my eyes floated to the drawings of her young child stuck proudly on the cabinets. I was so proud of her resilience, for beating the odds and fighting for her dreams.

“I still breathe a prayer for this family whenever I pass by on my bus rides.

“That is the joy of being a social worker – seeing families like this one who, despite having been dealt a tough hand, choose to not give up. They write their own narratives and find ways to fight for what they hold dear”.

From garang to burnout

After three years of being “a garang (gung-ho) social worker”, Koh faced the “very real impact of the work”.

“There are many names for it: Burnout, compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma.”

This is not uncommon to those who work in mental health services or healthcare. “Every social worker or helping professional has experienced it to some degree, though it’s hard to admit. On a daily basis, we encounter and attend to clients’ stories of trauma, stress, sickness and loss. And that leaves an impact.”

“I am not superwoman. I had to lose illusions that I could do it all.”

After a particularly difficult case involving suicide and family violence, police and statutory involvement, Koh experienced nightmares and hypervigilance – symptoms of secondary trauma.

“This realisation was deeply unsettling and humbling. It was a turning point for me.

“I realised how crucial it was to ‘do the work’ in my own healing journey.

“I am not superwoman. I had to lose illusions that I could do it all. I had to reach out and ask for help.

“There is no shame in getting help.”

Her organisation supported her with her personal therapy. She was able to share and process what she was going through with colleagues she felt safe with.

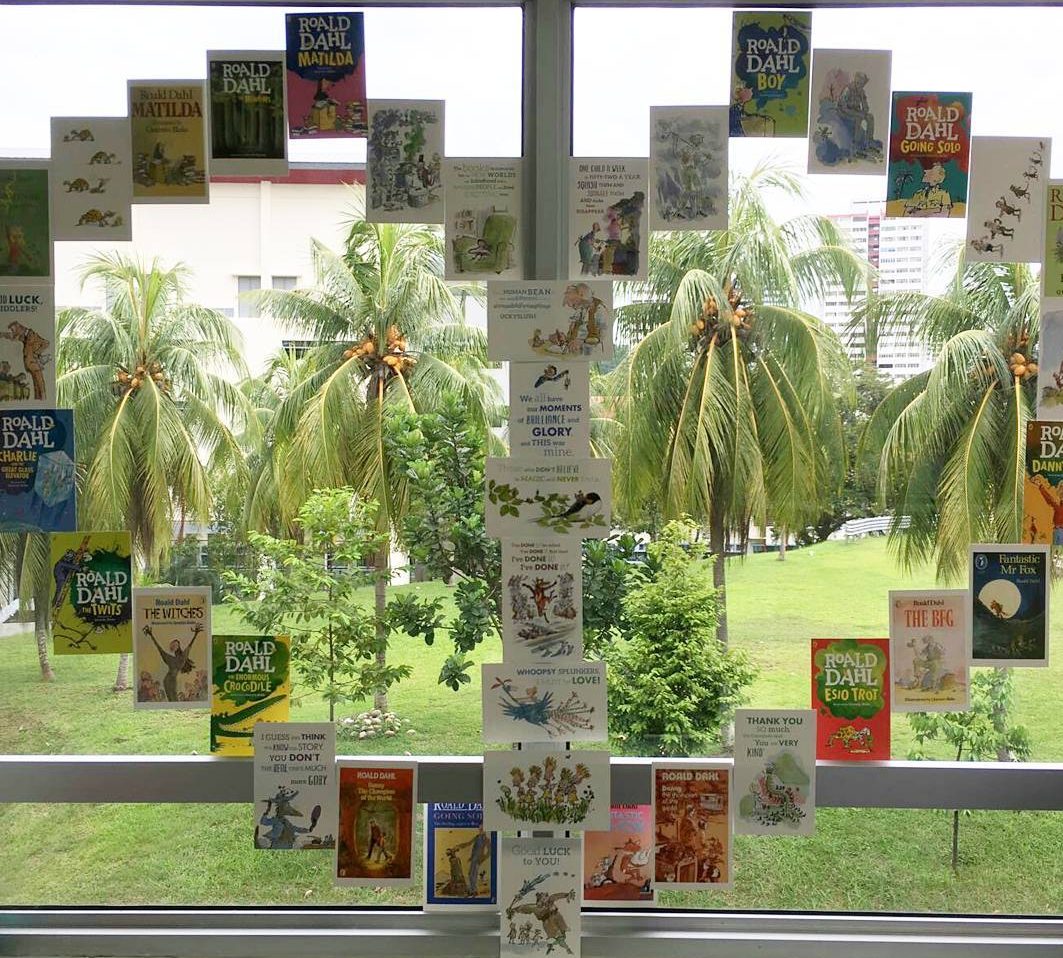

Reminders to be loving and kind to themselves. Koh and colleagues put up a heart-shaped display of Roald Dahl postcards. They also set up an art corner where colleagues could doodle or colour to relieve stresses of the day, and a small mamak shop of snacks where they could grab a “perk me up”.

Koh’s clinical supervisor encouraged her to “practise radical self care”.

Koh picked up pilates which helped her tune into her body. She drew healthier boundaries – “learning to say no, paying attention to when my body and emotions are signalling that I am overloaded, and knowing that I cannot do everything for everybody”.

Also important were bi-monthly small group “psychological debrief sessions” with five to six colleagues. “We would use expressive mediums to share and process the impact and meaning of our work in a safe environment.”

Going for personal and spiritual retreats, and seeking spiritual direction, were also important.

In time, her symptoms faded away.

“I knew that, even in my pain, God was with me and God is sovereign.”

The risk of secondary trauma never really disappears, she says. “I had to learn to recognise the signs, sit compassionately with my emotions, listen to my body, get the right kind of support, and build my resources to cope.

“It sounds strange doesn’t it?” Koh muses. “Aren’t we, the helpers,” supposed to be “steady, calm, professional, always having a smile on our faces”?

“But we are human.

“Those of us in the helping professions are expected to do a lot. We also expect a lot from ourselves. It can be a draining. And things like paperwork can sometimes snuff out our joy.

“Serving a purpose can often override attending to our own needs. When we do not take care of our body, it will start to break at the seams.”

Work should not also define one’s identity. She “learnt this the hard way” when her health suffered badly.”Going the extra mile for clients can be seen by others as good work. But I’ve learnt that it can also come from a place of pride and wanting to be recognised.”

2-in-1 healing

In 2017, Koh had a fall. She was later diagnosed with a cervical disc herniation. Her left arm felt numb due to a compressed nerve root. She would have sudden shooting pains down her arms.

At the same time she was struggling to release bitterness and anger not related to her injury.

To focus on her recovery, she left the agency where she had been working for eight years.

At the first of several healing services she went to, she responded to a prayer call for someone with “numbness and vertebral issues”.

She experienced “a new God-given strength to love” the people who were causing her to feel hurt and angry.

She was surprised. She stood up for prayer. Tears streamed down her face. “I felt God speak: ‘If you had to choose between Me healing you physically or emotionally, which would you choose?’

“My response was: ‘I know you can heal me in both, God. But you’ve shown me what I need more. So if I really had to choose, I choose emotional healing.'”

She immediately felt a warm sensation on her neck. That night, there was a significant improvement from the pain. She also experienced “a new God-given strength to love” the people who were causing her to feel hurt and angry.

But the physical pain would ease and return over the next seven months of “on and off healing”.

She felt “depressive feelings creep up”. Especially on days she would lie in bed in pain and needed her husband’s help to dress.

Her specialist recommended surgery to stem permanent nerve damage to her spinal cord. “It was a scary decision. I prayed that God would spare me. I struggled with why God didn’t heal me. But in my spirit, I knew that God can heal physically at the snap of His fingers.”

One day, a deep sense of peace came upon her. “I knew that, even in my pain, God was with me and God is sovereign. And He can choose to heal through medical procedures.

“I could finally decide to go ahead with the spine surgery. Knowing He would protect me and help me recover.”

She believes that she needed those seven months to let go of the emotional hurts. “I would tell God: ‘I am trying, but the triggers just keep coming. It was too hard.'”

“When we reach the end of our rope, He is there to embrace us and heal us.”

When she realised she was trying to forgive out of her own strength, she surrendered to God. The emotional healing eventually came. In place of “waves of pain and anger”, she felt a “Christ-like love”.

“I felt a deep peace and a lightness.”

Three weeks before she was due for surgery, a pastoral staff approached her after church service to pray for her. He felt God was saying that He would heal her. The symptoms disappeared and remained that way.

It was a “joyous day” when her surgeon agreed that the operation could be cancelled. She calls it a “2-in-1 healing”.

“God has been merciful, He always is. When we reach the end of our rope, He is there to embrace us and heal us when we finally give way. He nurtures and heals us.

“When you pass through the waters, I will be with you; and when you pass through the rivers, they will not sweep over you” (Isaiah 43:2) is the verse she clings to when attending to crisis cases, and in her own journey.

From wounded to healer

From her work with children and youth affected by traumatic experiences, Koh embarked on specialised training in play therapy to equip herself to further help them.

“I chose to train as a play therapist as it had a good body of research.

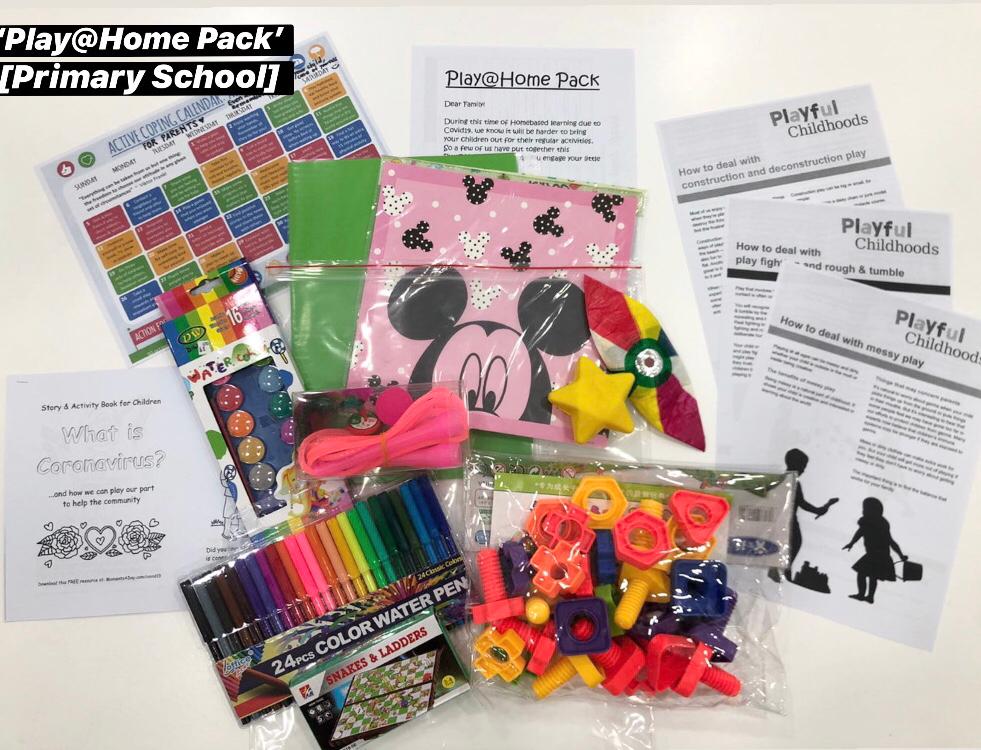

Koh and a team of volunteers have supplied social service agencies with 350 Play@Home packs to distribute to families with less access to resources. With recent support from the Singapore Strong Fund, they will be able to provide an additional 300 packs.

“It is God’s calling and a passion He placed in my heart.”

Reacting to the announcement that schools were moving to home-based learning, Koh started the project Play@Home Packs. These would help families with less access to resources engage with their children during Circuit Breaker.

She and a team of social workers, counsellors, play therapists and teachers curated, sourced and packed the packages for three different age groups: Preschool, primary and youth. These packs are distributed through social service agencies.

“How can we put our woundedness in the service of others?”

Even though play may seem non-essential, the power of play and bonding cannot be overlooked, Koh said in an interview with Thir.st on projects that Singaporeans can contribute to.

“Play is a child’s way of coping with the changes and challenges they face, including COVID-19.”

On her journey as a social worker and play therapist, Koh says she has seen God’s hand clearly.

In the process of “entering the sacred and sometimes dark place of a person’s trauma, there are times I encountered my own wounds”, she says.

She cites the words of Dutch Catholic priest and theologian Henri Nouwen: “Nobody escapes being wounded. We all are wounded people, whether physically, emotionally, mentally, or spiritually. The main question is not ‘How can we hide our wounds so we don’t have to be embarrassed’ but ‘How can we put our woundedness in the service of others?’

“When our wounds cease to be a source of shame, and become a source of healing, we become wounded healers.”

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light