“I was no longer hearing God”: Nobel Peace Prize nominee Tony Meloto on confronting the poverty of his own soul

Emilyn Tan // September 6, 2023, 2:08 pm

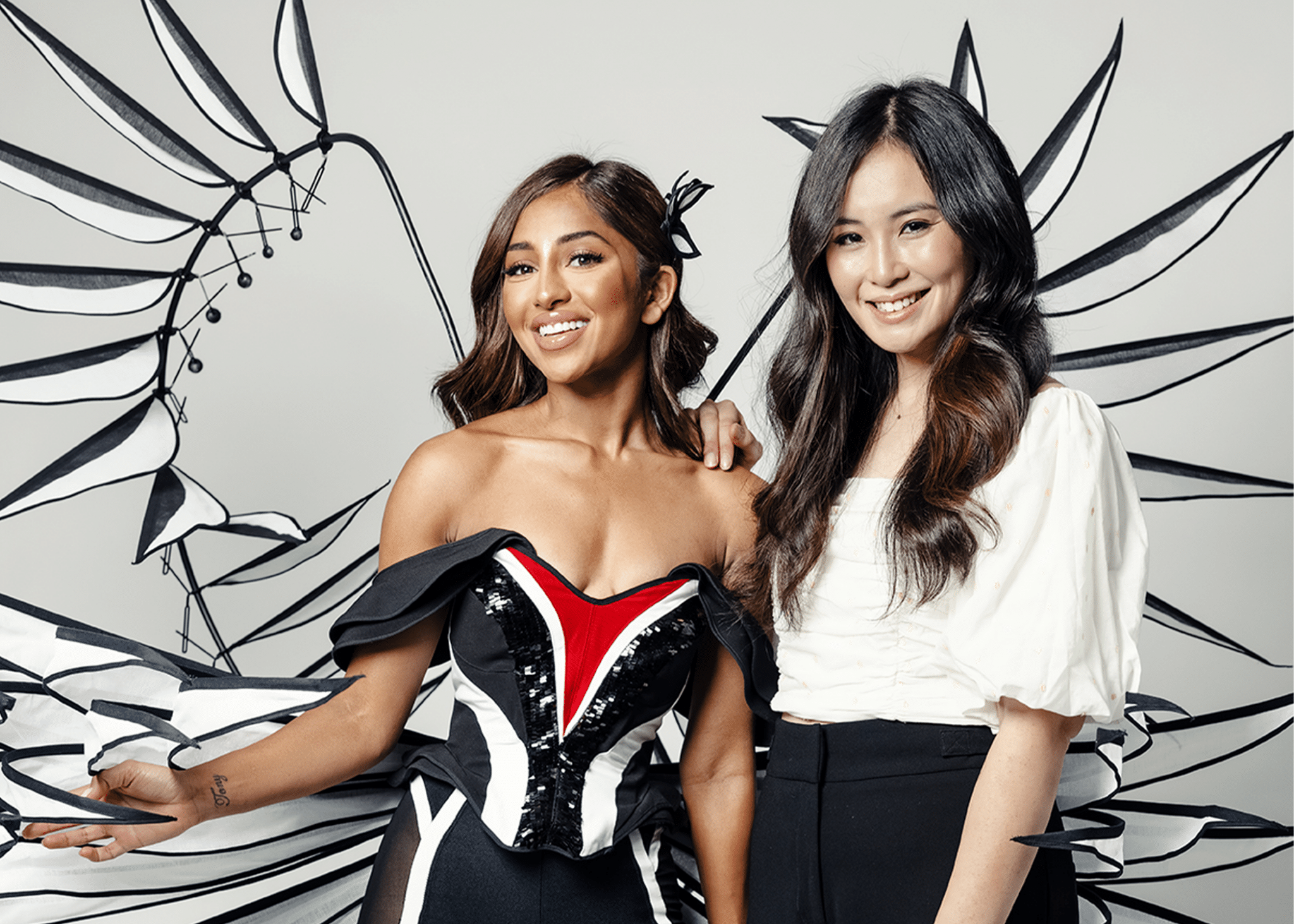

“The biggest poverty of old age is loneliness," said award-winning NGO Gawad Kalinga's Tony Meloto at the Eagles Leadership Conference in July 2023. His journey of spiritual renewal and purpose of empowering the old have since become “the biggest blessing in my life”. Photo courtesy of Eagles Communications.

Social activist Antonio (“Tony”) Meloto had long been a victim of psoriasis when the anguish of growing old added to his deepening despair.

The founder and chairman of Philippines-based Gawad Kalinga (GK), a poverty alleviation non-governmental organisation (NGO), was slowing down with age. But the chronic autoimmune disease taunting his body with its trademark red, dry, scaly skin lesions was not.

In June 2022, at age 72, Meloto released an impassioned outcry entitled “The Poverty of Old Age: Life After the Glory”.

He wrote that, away from the limelight of being a Nobel Peace Prize nominee, the winner of multiple awards and a highly sought-after speaker, “back in my hotel room, I was the tired, old, sad and lonely messenger coping with pain from sores and joints, quietly applying steroids on an aging body covered with scales and patiently wiping the pus and the blood from the wounds in my most private parts”.

“It is difficult. Being a leader of movements, you’re expected to be perfect.”

It was penned to no one in particular but went viral on social media.

A year later, at the Eagles Leadership Conference (ELC) in July 2023, he testified: “Amazingly, simply because I was moved by God to write about my vulnerability, psychiatrists and dermatologists invited me for lunch.

“And they discussed with me that the toxic drugs I was taking was actually causing inflammation of my brain.”

The medical specialists told him that the anti-cancer drugs with which he was self-medicating for temporary relief were liver-damaging. Furthermore, psoriasis had links to psychosis, high suicide rates and perhaps a 50% incidence of depression among sufferers.

“No one had explained it to me,” Meloto said. “I just suffered.”

He had been drinking heavily behind closed doors to cope, finding himself incapable of confiding even in his family, in order to “spare them the pain”.

“It is difficult. Being a leader of movements, you’re expected to be perfect.”

Down in the slums

Meloto wasn’t always a social activist. He was a strategy manager for Proctor & Gamble for 20 years and a missionary before being rudely disquieted after he and his wife awoke one night “to find two men naked from the waist up, about to ransack our house”.

“We will always be threatened by our neglect of the less fortunate.”

They allowed the pair to escape before calling the police. Investigations later traced the intruders to the slums beyond the residences where the Melotos lived with others of similar socio-economic stature.

That piece of information propelled him to scout out Bagong Silang, Caloocan City – the biggest slum area in Metro Manila – every day and eventually begin a youth development programme there in 1995.

Not only had he come face-to-face with the dire need of his destitute neighbours, he also knew this: “We will always be threatened by our neglect of the less fortunate.”

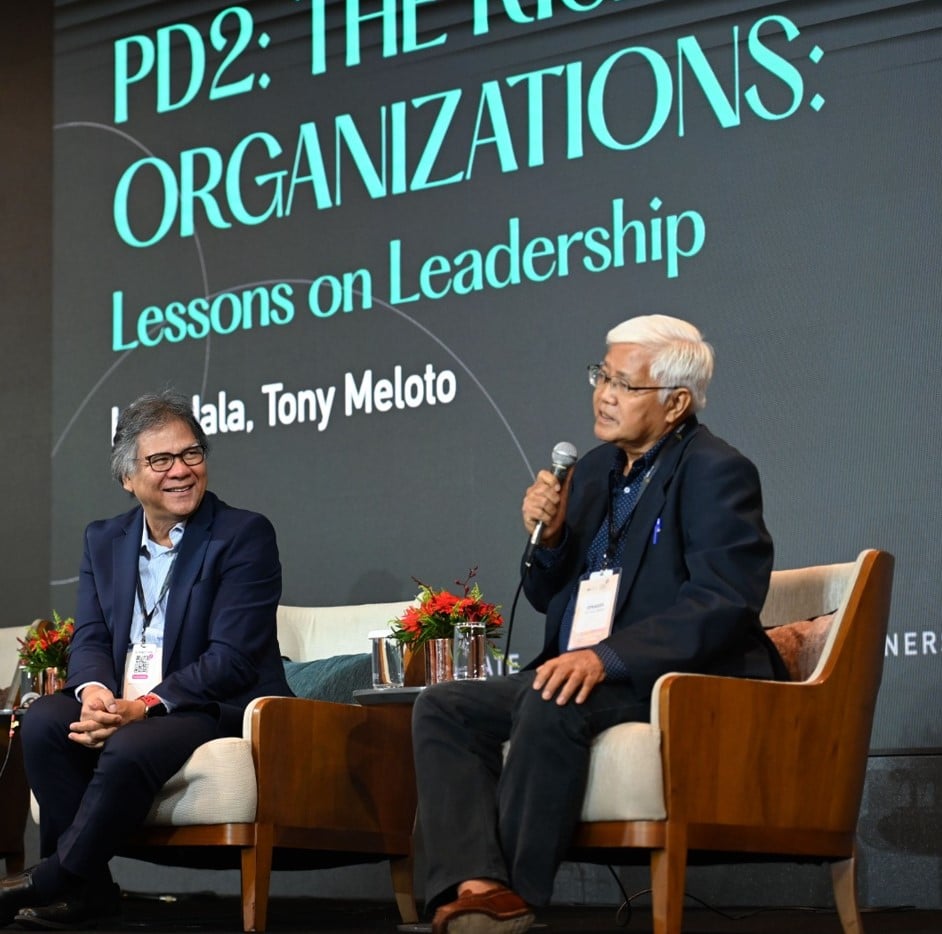

Speaking at ELC’s “The Rise and Fall of Organisations: Lessons on Leadership” in a plenary session with Malaysian technocrat Dato’ Sri Idris Jala, Meloto recalled: “I had nothing to bring except bread and coffee, but I came to discover the power of presence.”

“I came to discover the power of presence,” Meloto (right) said of his first venture into the Philippine slums. He was co-speaking at ELC with Dato’ Sri Idris Jala (left). Photo courtesy of Eagles Communications.

The courage of his convictions was such that he involved his two university-aged daughters in the work, knowing full well they would be mingling with roughshod gang members and criminals.

The greater burden on his heart was the rehabilitation of the slum community. Thus Gawad Kalinga (GK) was birthed.

“I would go early in the morning, because you have to have the common sense not to go in the afternoon because the criminals would be drunk or high on drugs; and you also had to bring their mothers, because even criminals are afraid of their mothers.”

These women were GK’s first volunteers.

“We prayed,” he recounted, and a sense of mission arose.

“Bring their mothers, because even criminals are afraid of their mothers.”

Their collective effort grew in the next seven years to over 3,000 communities across the Philippines. Meanwhile, Gawad Kalinga was formally registered as an NGO in 2003.

But the gains were not without losses. Fourteen members were killed in this span of time when they turned away from their previous life of crime.

Meloto shared: “They surrendered their weapons and, along the way, they were killed by their former enemies. We were not fast enough in transforming the environment.

“As we built the first 30 homes, we realised that you have to build a community, you cannot just transform individuals. You have to build communities and you have to do it by connecting with the community through collaboration.”

Back to basics

With GK’s success in the Philippines, Meloto’s God-given assignment of creating sustainable communities within slum areas was rapidly expanding into other countries. Everywhere he went, the abiding strategy was to make the work:

- doable

- visible: “We painted the homes in bright Benetton (an Italian clothing brand) colours, to really make it visually attractive.”

- quantifiable: “How many homeless did we shelter? How many children who were hungry did we feed? How many did we send to school?”

- sustainable

- replicable

Sunny side up: Gawad Kalinga homes are painted in vibrant “Benetton colours”.

Every grain of rice: Bento boxes are distributed to meet the community’s need for nourishment.

In GK communities, schooling takes place even in informal settings. Above photos from www.gk1world.com/GKBI.

The slum-dwellers typically would step up to the task of building, rather than being passive recipients of charity.

“Since they had no money, they provided sweat equity. They actively were partners in the development of their own community.”

From his own country, Meloto received the Ramon Magsaysay Award (dubbed the “Nobel Prize of Asia”) for Community Leadership in 2006.

“Since they had no money, they provided sweat equity. They actively were partners in the development of their own community.”

Five years later, in 2011, he was recognised with the Nikkei Asia Award in regional growth “for his commitment to improving the living conditions of the poor”.

“He has made life better for residents in slum areas by constructing more than 200,000 homes in 2,000 communities in the Philippines and in other developing countries such as Indonesia, Cambodia and Papua New Guinea,” noted the Nikkei Asia Award tribute.

In 2012, he was lauded by the World Entrepreneurship Forum with the Social Entrepreneur of the World award.

“It was clear that it was God’s work, because I wasn’t trained in college or in my career to be a community developer. I was not an architect or engineer to build homes for the homeless, to do community planning,” said Meloto, whose university degree was in economics.

“I just had to move with the Spirit. The science, the system, the structure, the succession came later.”

The hidden truth

However, Meloto’s meteoric rise to global fame would come to a crashing halt after his closing address at the 2016 World Forum for a Responsible Economy in Lille.

Staring at the sea of faces giving him a glorious standing ovation, “I felt such a great anxiety that I almost jumped off the stage”, he recounted at this year’s ELC.

“I just had to move with the Spirit. The science, the system, the structure, the succession came later.”

“You have a unique story to tell, and they wanted to hear it, but it was already storytelling. It was no longer inspired by the Spirit, and so you feel empty.”

The reckoning was personal. Detailing his inner turmoil and the almost palpable fear of dying, he said: “I realised that I was fighting with an enemy within myself that I did not know.”

Once back in the Philippines, he drank through an entire night, then took an early morning flight to Bacolod City, his home province.

“Everyone looked for me, but I disappeared.”

He had sought refuge with his 100-year-old mother who was, by then, deaf and blind. Sitting by her bedside in her twilight, “I felt the comfort of maybe a child inside the womb, just holding her hand”.

She would pass on two months later.

“I realised that I was fighting with an enemy within myself that I did not know.”

Raking through his past and pondering the future, Meloto found himself meandering towards a crossroad. (Jeremiah 6:16)

“The reason why I became more depressive was: At the height of the success and glory of the movement, I was no longer hearing God. I was hearing myself, and I was hearing more all the praises, the adulation of the world, the awards from everywhere.”

He made the decision to turn down speaking engagements and detach himself from social media, dialing back to “nothing”. It was a matter of surrendering everything to God.

“But it’s not that easy,” he confessed. “You have to confront your own demons.”

The season of spiritual wrestling would prove to be deeply renewing.

“I discovered the power of silence,” he said. “I came to realise that maybe I should listen more and talk less, because I was like a vending machine: You dropped something, and I would talk.”

New life

The journey since has been “the biggest blessing in my life”, with its outworking being the determination to combat what he called “the poverty of old age”.

Rising up from being reduced to a nobody as a senior – “you have lost your power, your value, your worth” – Meloto discovered rest in a life of daily prayer, as well as regeneration.

“Our goal is to really do whatever it takes for us to give people a reason to live again.”

His psoriasis has been helped by a switch to organic medicines, and the inflammation in his brain has been addressed.

“I spent seven years in silence to listen to the Lord again,” he said. “He gave me this new mission to care for the elderly, who have been forgotten by society.”

Through the GK Enchanted Farm, described on its website as a platform to raise social entrepreneurs from among local farmers, the public is encouraged to participate in its farming activities and engage with the elderly in the GK community.

Meloto, now 73, elaborated: “The biggest poverty of old age is loneliness. The old people are forgotten and neglected, because the younger ones are too busy building their own careers.

“The more successful seniors are not spared, if they have no sense of purpose.

“And it’s not just in our country but in many parts of the world.

“Our goal is to really do whatever it takes for us to give people a reason to live again, so we take it day by day.”

“The power comes from God, not from us who begin movements.”

In similar vein as GK did with slums, the Enchanted Farm effort is also moving into different towns, seeking to empower volunteers who are about to retire “and who are scared of getting old”, or who are younger people performing the role of caregivers.

“At the heart of this is that we have found Jesus at the centre of our life. And that is the commonality in building community.

“It is a faith journey. And it is the faith journey of an imperfect leader with no claim to political or economic power. That has given me so much freedom, just to be detached from so many of the world’s attachments.

“At the depth of my pain, my loneliness, my sadness, I discovered that it is in making those with greater pain happy that we become happy ourselves.

“The elderly who are lonely, unhappy, hungry – we have the power to make them happy. It is something that the most ordinary person can commit to.

“The power comes from God, not from us who begin movements.”

MORE FROM THE EAGLES LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE:

Falling into grace: What moral failure taught a reverend about God

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light