Humanitarian crisis in Myanmar: The anguish of a nation on the brink of civil war

Tan Huey Ying & Kelly Ng // September 18, 2021, 7:50 pm

Myanmarese keeping a candlelight vigil earlier this year. Photo by Zinko Hein on Unsplash.

Youths in their 20s, holding up slingshots in a face-off with soldiers armed with machine guns and rocked-propelled grenades.

A long trail of vehicles carrying corpses to the crematorium, which cannot burn the bodies fast enough.

Thousands, including babies and young children without food and shelter, seeking refuge in the forests of Chin state.

These are some of the horrific scenes described to Salt&Light by eye witnesses over the months since the military coup descended upon Myanmar on February 1, 2021.

To date, more than 1,000 people have been killed and over 7,000 people arrested since the coup – including about 70 children detained as proxies for their parents – according to reports by advocacy groups.

Eyewitness reports verified by international news agencies say that many were killed by a shot to the head and casualties were not limited to protestors, but included bystanders and children.

Myanmar demonstrators shout slogans as they march on a street during an anti-military coup protest in Mandalay, Myanmar. Photograph by EPA.

Prisoners have been tortured. A poet, who had written that “revolution dwells in the heart”, was arrested. His body was eventually returned to his family without his heart and organs.

Last Tuesday (September 7), Myanmar’s shadow government, the National Unity Government (NUG), issued a call for a “people’s defensive war” against the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military junta.

Escalation to D-Day

A few days ago, Thiha*, a community leader in one of the resistance groups, spoke to Salt&Light through a translator on condition of anonymity.

“In Hakha where I live, we experience shooting and bombings every day since September 7.”

Over a secure line, he said that the situation is “deteriorating” and has become “a lot more tense” after the NUG’s “D-Day” declaration.

He had been involved in the 2020 November elections, but is now “working on the ground”.

“Life before September 7 was tough, but things have really intensified now,” Thiha said. “There has been more fighting and a lot of bloodshed.”

Pastor Shien*, who is based in Hakha, the capital of the Chin state, told Salt&Light: “Many things can be said of the situation on the ground – the situation differs from one location to another. But explosions are happening in many parts (of the country).

“In Hakha where I live, we experience shooting and bombings every day since September 7,” she added.

“They use heavy weapons, such as helicopter fighters.”

“The (civilians) had chosen peaceful means. This (fighting) is the last resort.”

Salai Van Biak Thang, program director at the Chin Human Rights Organisation (CHRO), which is actively monitoring and documenting human right violations, pointed out that the bombings are taking place “indiscriminately” in residential areas and the military are occupying religious infrastructure.

Now based in India on the border of Mizoram, Van Biak had to go into hiding after his home was raided by soldiers and police.

“Since (D-Day), people have become more active,” he said. “We have seen many more incidents – almost everywhere now – people fighting back against the military.”

Communications towers by Mytel, a military-owned outfit, have been the targets of anti-coup protestors and several have been destroyed in the week after the NUG issued its rallying cry to war.

The extreme violence by the Tatmadaw towards peaceful protestors was the last straw for many, said Van Biak. “They had chosen peaceful means. This (fighting) is the last resort.”

Wielding slingshots and handmade air-guns against fully-equipped soldiers armed with machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades, 28-year-old Myat* found himself among other protestors facing down the Tatmadaw (Myanmar’s military junta) in one of the northern states in May this year.

After marching alongside other peaceful protestors in Yangon for the whole of February, Myat was one of the many young people who left the capital and other major cities to join a resistance group opposing the junta.

Myat told Salt&Light that, before the coup, he had worked for an international non-governmental organisation teaching civil servants and leaders – both in government and in the armed resistance groups – on federalism and democracy.

Decades of “no law”

Tom*, a foreign leader of a Christian organisation in Myanmar who has served the people for over 25 years shed some light on the current chaos and struggles in the country.

Though he lived there for over a decade, he had to leave Yangon in March as the violence intensified.

He explained to Salt&Light that when the Tatmadaw took power in 1962, they had set isolationist policies in place, believing that control of the country would be better maintained if people were kept disconnected from the world.

“Nobody wants to go back. They don’t want military dictatorship again.”

“There was no law. People lived in fear of being picked up (for questioning).

“If you were on the wrong side of the army, you were somehow always in the wrong,” Tom said of the oppression that existed when the army took over in 1962, even though it was without any open conflict since 1988.

That year, the Tatmadaw quashed an uprising against the junta and killed 3,000 civilians.

Everything changed when Myanmar started to open up in 2011, Tom said. Economic reforms were made and the inflow of foreign direct investment transformed the nation.

In 2008, Tom had paid 2,000 USD for his Myanmar SIM card which had to be procured through the black market. After 2011, basic items like SIM cards were no longer exorbitant.

“There was much more freedom and they became very modern in just five to eight years. Incredible transformation,” Tom said.

Yangon in peaceful times. Photo by vintag.es

Credit card payments were starting to be accepted, economic growth was on the rise. People got access to the internet, there was a freer press. Mobile phone ownership and internet access grew from around 8% in 2011 to over 80% in 2020.

After this February’s coup, people were saying: “Our future is gone.”

Many civil servants including doctors, nurses, and teachers walked off their jobs in protest.

“Nobody wants to go back,” said Van Biak. “They don’t want to live under a military dictatorship again.”

Church leaders risking their lives

Van Biak observed: “People (of all religions) are standing together in the fight against the junta. They are united against the same thing.”

“But because of this ongoing conflict and restrictions imposed by the soldiers, we have a humanitarian crisis that looks like it will get worse,” he added. Transport networks crucial to the movement of goods are policed by the Tatmadaw and mostly blocked.

Christian church leaders are “not just based in their churches now … They are outside, risking their lives to protect people”.

With both the NUG and Tatmadaw trying to gain international legitimacy, “crucial international aid will be hard-pressed to get through Myanmar’s borders”, leaving the people vulnerable to famine and disease.

He added that Christian church leaders are “very active” in terms of providing assistance to people in need. “They are not just based in their churches now,” said Van Biak. “They are outside, risking their lives to protect people.”

Thiha said: “We are in a really unthinkable, dreadful situation. We’ve lost our freedom and we cannot even stay in our houses. It’s not safe.”

People are “generally fearful of going out and moving around”, said Thiha. “These days, anything can happen. It could be a bad day and they could lose their lives.”

“Everybody is living with anxiety and trauma,” said Pastor Shien, who believes that civil war is imminent.

Even under military rule, five churches have come together to form a charity to support people in need.

Responding to how she sees of God’s purpose in this, Pastor Shien said: “God is not just watching from a far, distant place and watching us suffer. He feels our suffering with us. I wholeheartedly believe that God has a good purpose for us in the midst of this (Romans 8:28). Even if we cannot comprehend right now.”

Even under military rule, five churches have come together to form a charity to support people in need, Thiha told Salt&Light. “It’s a dark and challenging time for us. We started out with no resources, just wanting to do the work prayerfully, and somehow we have now managed to support a good number of people and families,” he said.

Van Biak believes it is time for Christians to unite – not just to stand for justice but to also lend a helping hand to people in need.

He remains hopeful: “This is a fight for justice; the road could be long and difficult. However, with prayer and holding our hands together, we can remain strong and move on.

To fellow believers, he had this message: “It is encouraging for us when you pray for us, even post a prayer on Facebook, because this is when we know that we are not forgotten.”

The God we can trust

All the interviewees that Salt&Light spoke to are worried about the cost of a civil war on the lives of Myanmarese who are caught in the middle – especially with the recent Covid wave that has overwhelmed the country’s healthcare system.

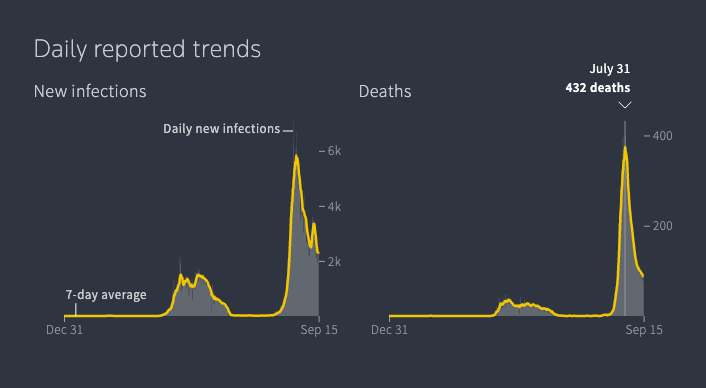

While infection numbers are generally on the decrease, Myanmar still faces more than 2,200 new infections and 70 deaths each day. More than 16,000 people have died since the pandemic began.

Current Covid numbers in Myanmar.

Most businesses across the country are closed. Banks are shut with a black market cash transfer system and food prices are on a meteoric rise. The currency has been devalued by more than 30% to date. And the healthcare system is overloaded to the point of near collapse.

Even those offering food aid to others risk being arrested.

Tom says that an estimated 500 pastors and church leaders have died from the most recent Covid wave in July.

“We realised a lot were traumatised – they need counselling.”

“After the coup, people were numb,” Tom said. “They were so …” his voice trailed off.

“You are overwhelmed by all that’s going on. Angry. Sad. Scared. Everything at the same time. People can no longer function.

“Then Covid came. So many died, we lost so many friends.” Tom recalled reading names off lists of friends and co-workers who had died. “Some said, ‘All I can do is cry.’ Others said, ‘We cannot cry anymore – there are no more tears left.’”

Still, Tom and his team knew they needed to take action to serve the communities they were in. “We realised a lot were traumatised – they need counselling.

“But we had to approach it differently because, the thing is, the trauma is not over yet. It continues everyday,” he said. “The fear, struggle and hopelessness continues.

“They can have a nice session, but when they’re done, they have to face it again.

“I know of young people who ask: Where is God now? My hopes of my future in my country are crushed … so what now? Where is God? How is He helping?

“I have many more questions than answers. I cannot – I don’t want to – answer people. Because, how can I know?

“But what has really helped me is that I know God. He is trustworthy.”

“Do I tell them a nice story which is made up in my mind? That Myanmar will be a free country? I don’t know. Your children will have a good education one day? I don’t know that too.

“But what has really helped me is that I know God. He is trustworthy. I do know and believe that His purpose is always to ultimately draw people to Him.

“What is happening now is not good – I don’t have to accept it as good. But I also understand who God is – I don’t understand His purposes. I don’t always understand His ways – His ways are higher than mine.

“And I also hear from people who really hold on to God: ‘If this life doesn’t work out, I have eternal hope. I will trust God.’ It comes down to their trust in God.

“Many are shaking, naturally. But I pray for them that they will hold on and not be angry with God. Pray for the Church, that the Christians will not be too devastated.”

Pastor Shien said that she is “very worried” about food shortages to come; people are not farming anymore “because it is so dangerous”.

“The secret things belong to the Lord. We just need to trust Him right now.”

She broke down while speaking: “We don’t really want to see people starving and dying from the civil war, especially with the Covid-19 situation.”

Responding to where she sees God in this, Pastor Shien said: “God is not just watching from a far, distant place and watching us suffer. He feels our suffering with us. I wholeheartedly believe that God has a good purpose for us in the midst of this (Romans 8:28). Even if we cannot comprehend right now.

“As a Christian who strongly believes in a just God, I always try to encourage people that God will bring His justice to us, and to show us the right or wrong.

“God is incomprehensible. He knows the end from the beginning. He knows our future minute by minute but He has no obligation to explain to us the reason for what happens in our lives and what’s happening in our country.

“The secret things belong to the Lord our God (Deuteronomy 29:29). We just need to trust Him right now.”

*Names have been changed for the safety of the interviewees.

If you would like to help in relief efforts in Myanmar, contact New Life Christian Centre, which is raising funds for food distribution and other critical aid.

MORE NEWS ON MYANMAR:

“Help! We can’t breathe”: Pray for Myanmar, struggling to get oxygen as dead bodies pile up

The shaking of Afghanistan and Myanmar: Our call to prayer and action

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light