A Bicentennial look-back at the extraordinary history of the Singapore Church

In celebration of our 54th National Day on August 9, Salt&Light brings you a series of remarkable Singapore faith stories.

Salt&Light // August 4, 2019, 11:13 pm

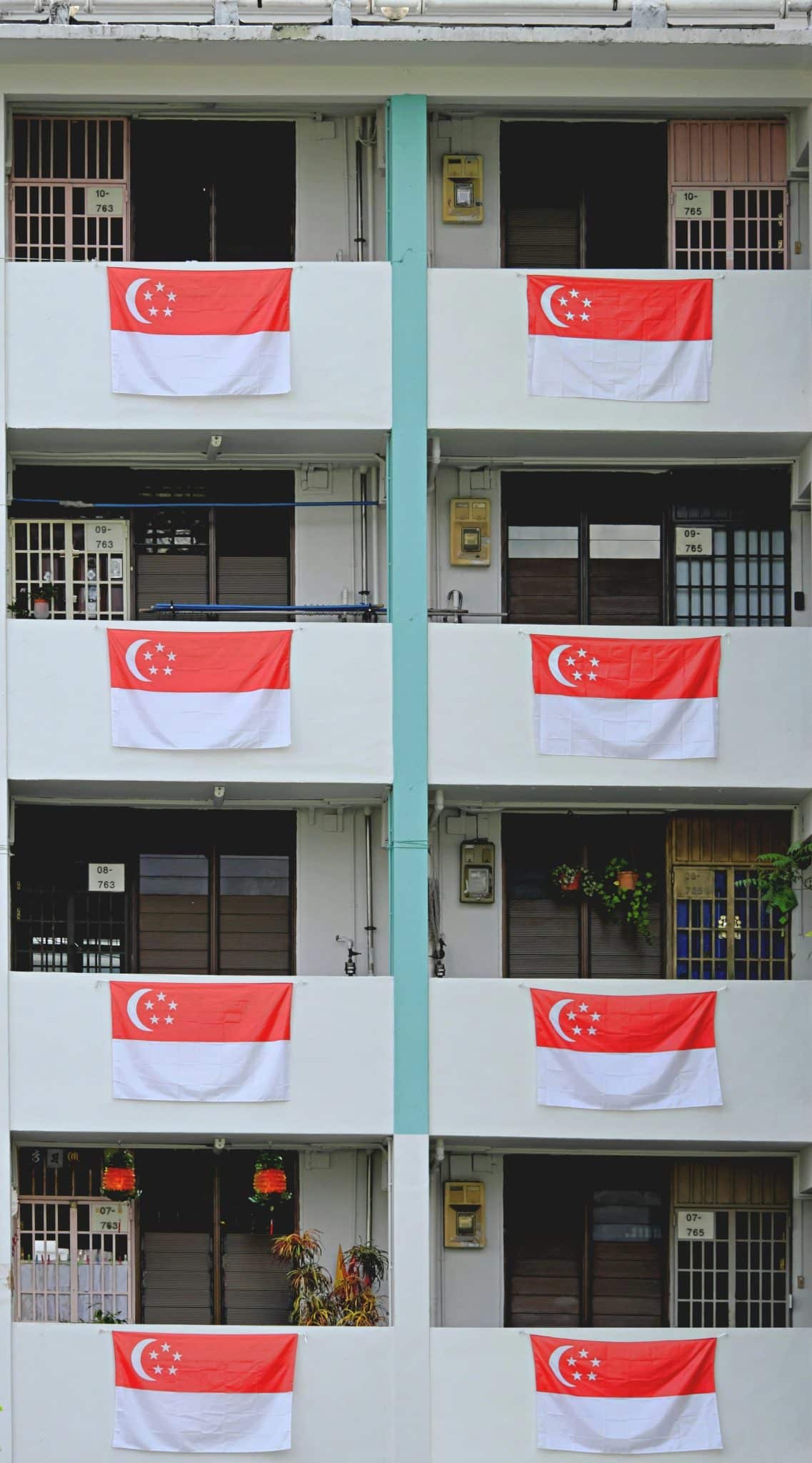

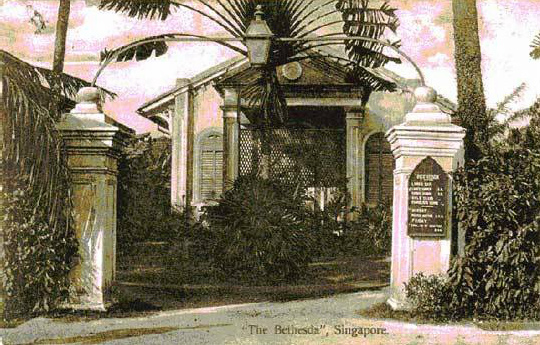

The first local Brethren Chapel at Bras Basah Road was built in 1866. Dr Benjamin Sheares, the second President of Singapore, was baptised at this church. It has since been relocated and is now called Bethesda Hall (Ang Mo Kio). Photo from http://bethesdadepotwalk.net, circa 1800s.

Intrigue. Torture. Loyalty. War and peace.

The dramatic history of the Church in Singapore had it all.

As we celebrate Singapore’s Bicentennial – 200 years since Sir Stamford Raffles’ arrival in 1819 – Salt&Light looks back at how our history and our faith are inextricably intertwined.

1819: Christianity sails in with Raffles

Sir Stamford Raffles’ arrival in 1819 marked the turning point in Singapore’s history. It also marked the arrival of the Christian faith.

Raffles, who had earlier set up the Java and Sumatran Auxiliary Bible Society, was keen to import the Word of God into the new trading post that was Singapore. He paved the way for the Bible Society to be established in Singapore.

Hot on Raffles’ heels were the Catholic and Protestant missionaries. Within a few years they, too, followed suit to preach the Good News and to do social good.

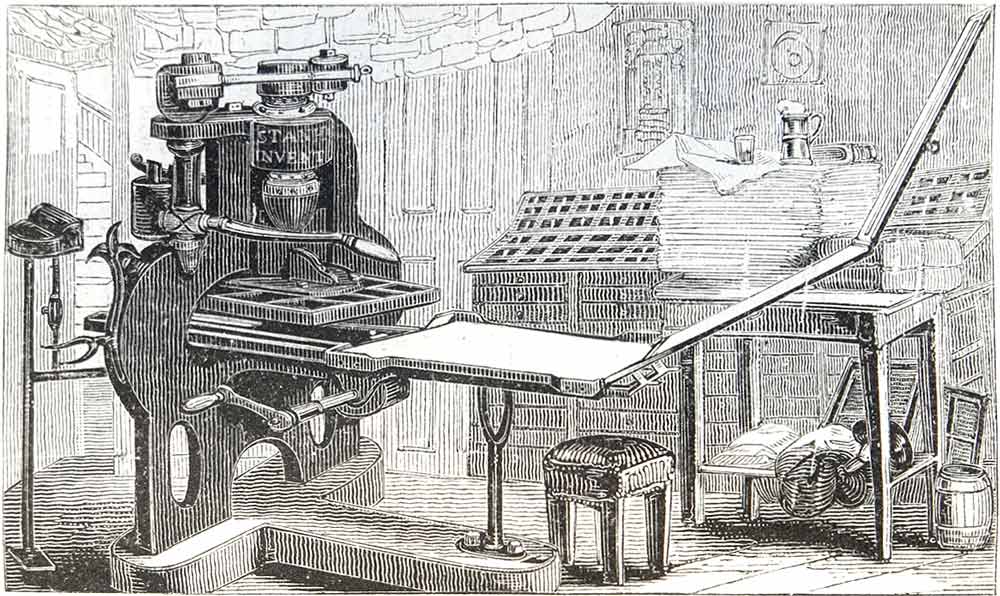

Protestant missionaries who first came were sent by the London Missionary Society. They brought their printing press and were soon producing Scripture, tracts and catechism material.

Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles paved the way for the Bible Society to be established in Singapore. An oil on canvas by George Francis Joseph, 1817 [Public Domain].

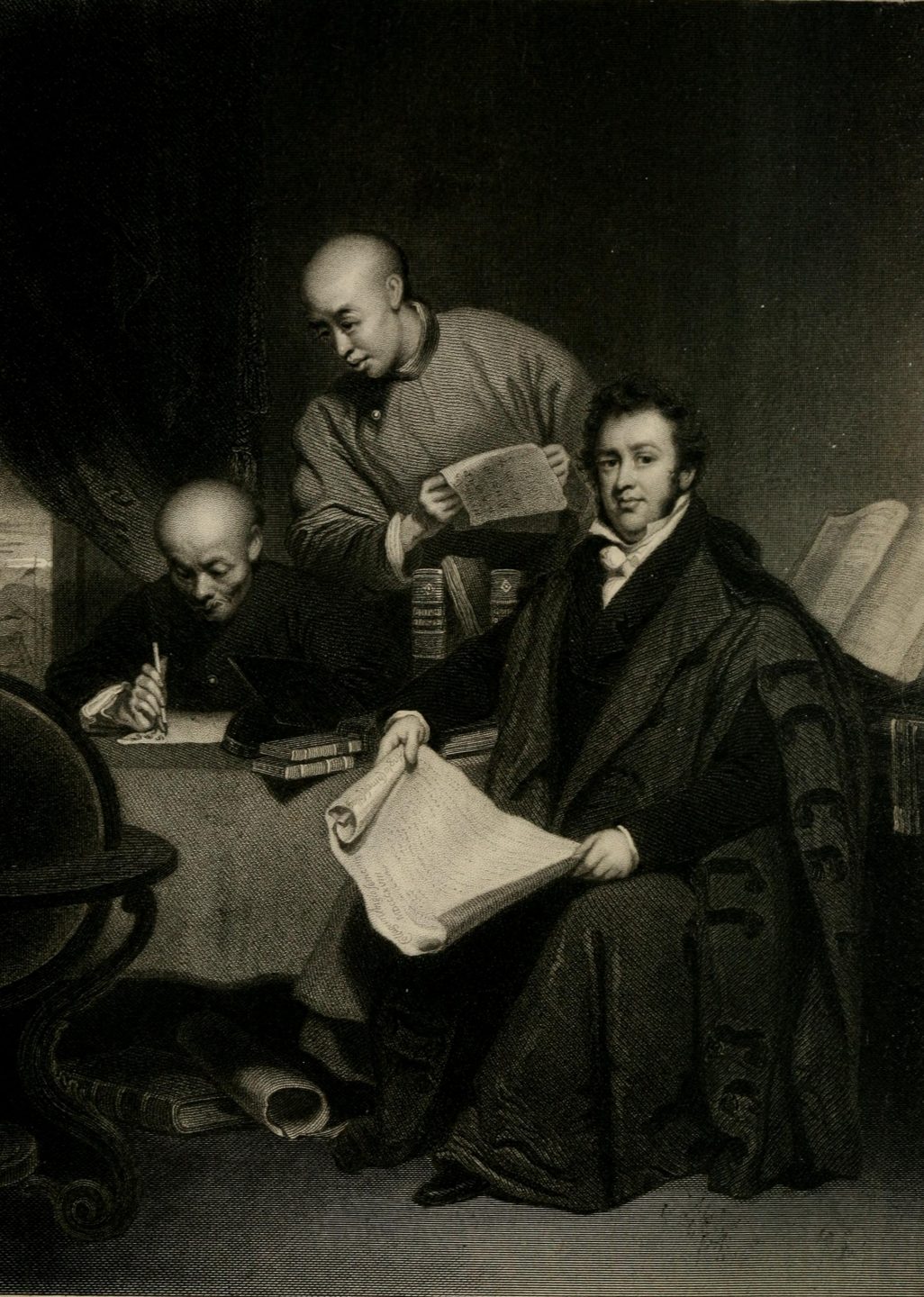

Robert Morrison (1782-1834) (right) pioneered the translation of the Bible into Chinese. An engraving by Jenkins [Public domain].

Reverend Claudius Henry Thomsen introduced the first printing press to Singapore in 1822. Besides printing in English, Thomsen was also the pioneer printer of Malay-language publications in the Malay Peninsula.

1829: Missionaries build schools

One of the living legacies of the Christian missionaries is the schools they started and the education they provided for a local people who were hardly literate at the time.

By 1829, the missionaries were running four schools: Two teaching in Cantonese, one in Hokkien and another in English.

The early missionaries took efforts to master the local languages: Malay, Tamil and the many different Chinese dialects.

By 1829, the missionaries from the London Missionary Society were running four schools: Two teaching in Cantonese, one in Hokkien and another in English.

Many students of these schools came to the faith, as there was always time set aside for studying the Scriptures or examining how the missionaries live out their Christianity.

The mission schools also provided safe havens for orphans, abused and unwanted children.

The Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (CHIJ) opened its doors in 1854 with a mission to educate girls. It ended up running an orphanage as well, as babies were left at their door step, sometimes just bundled loosely in paper. (When CHIJ moved to its current premises in Toa Payoh, it closed the orphanage.)

Many of the mission schools continue to thrive today and have produced many leaders in government, commerce and churches over the last two centuries.

Sophia Blackmore (1857-1945) (middle) founded both Fairfield Methodist School and Methodist Girls’ School. She also set up a boarding home for girls. Fluent in Malay, Blackmore often conducted open air meetings in the language and published a Christian periodical in Baba Malay. Picture from http://withkidswego.blogspot.com

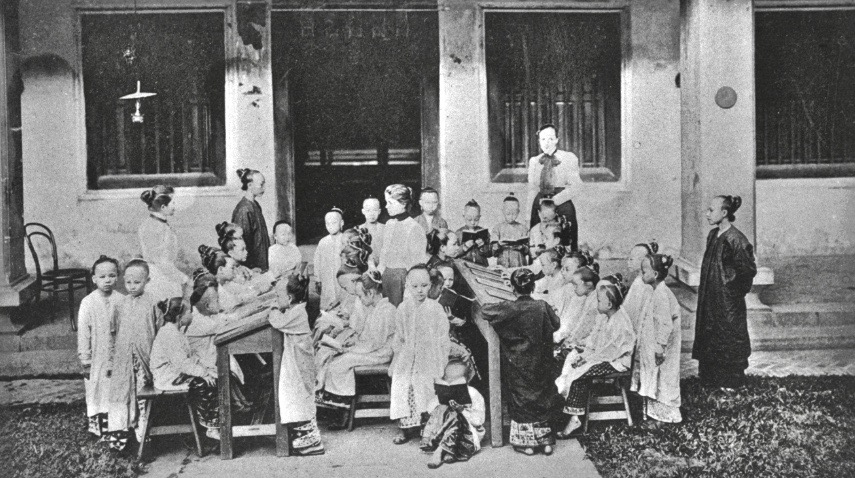

Chinese Girls School (CGS) was the first all-girls’ school in Singapore. It was started in 1842 by an English missionary. Miss Sophia Cooke ran the school from 1853 to 1895. She was active in the community, and worked with the sick and needy. Miss Cooke was also the founder of YWCA, Singapore. In 1949, CGS was renamed St Margaret’s Girls’ School. The school is still thriving today. Picture from Frank and Frances Carpenter Collection [Public domain].

Those who could not afford to keep their babies often left them at CHIJ’s side gate, which came to be known as the “Gate of Hope”. The children were taken care of and given an education. Picture from biblioasia.

1835: Churches build a firm foundation

Within 20 years of its founding, Singapore grew from a backwater fishing village to a major trading post.

By 1840s, several churches from the different denominations had been built. The Armenian Church, completed in 1835, is Singapore’s oldest.

The Treaty of Nanking (Nanjing) signed between the United Kingdom and China brought the First Opium War (1839–1842) to a close, and opened up China’s doors to Westerners, including missionaries.

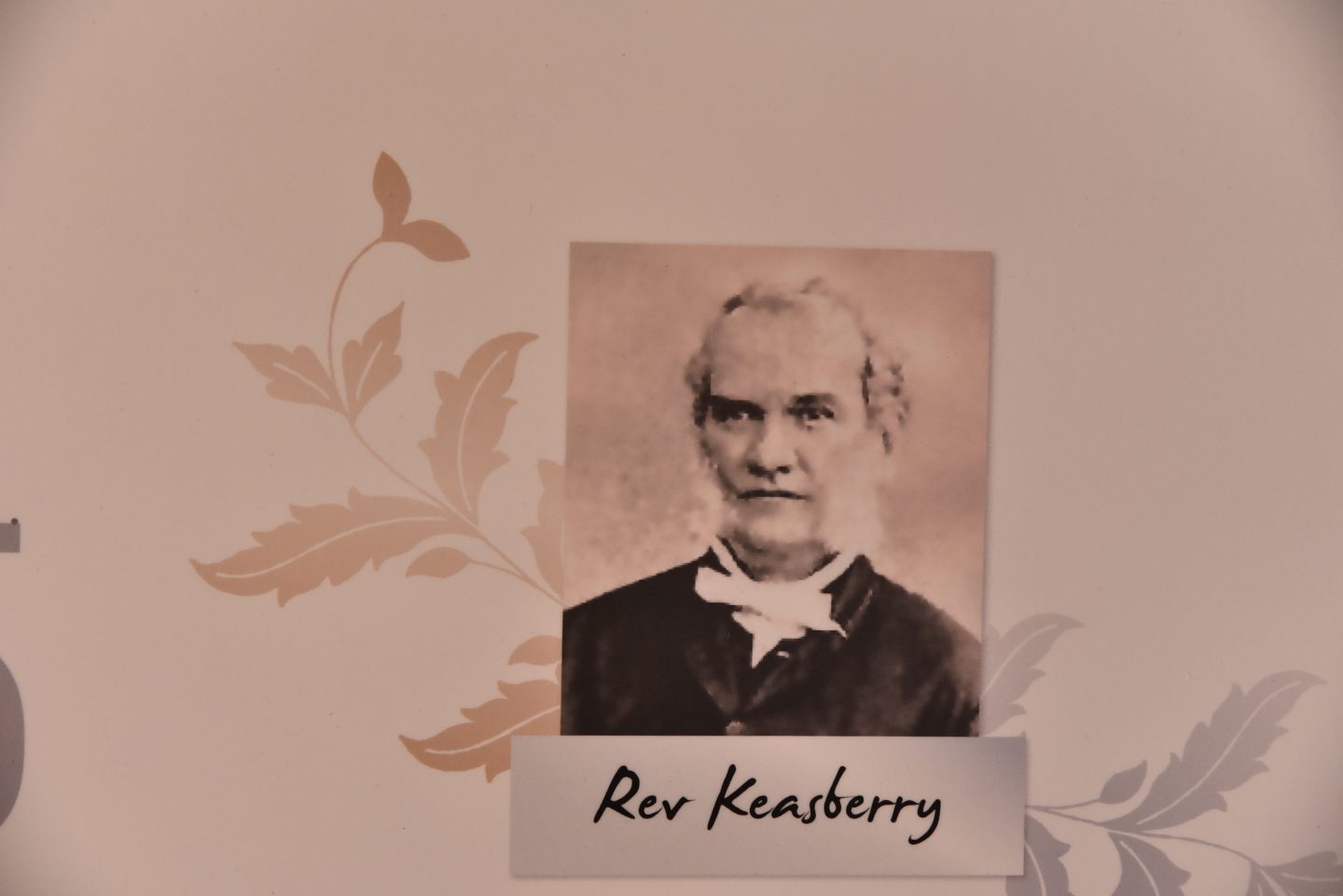

Rev Benjamin Keasberry spoke Malay and was naturally drawn to the Malay-speaking community which included the Peranakans.

By 1846, almost all foreign missionaries working in Singapore were asked to leave for China as their mission organisations made plans to relocate.

One missionary decided to remain in Singapore.

Benjamin Peach Keasberry, previously stationed in Batavia (present day Jakarta, Indonesia) had arrived in 1837. He spoke Malay and was naturally drawn to the Malay-speaking community which included the Peranakans.

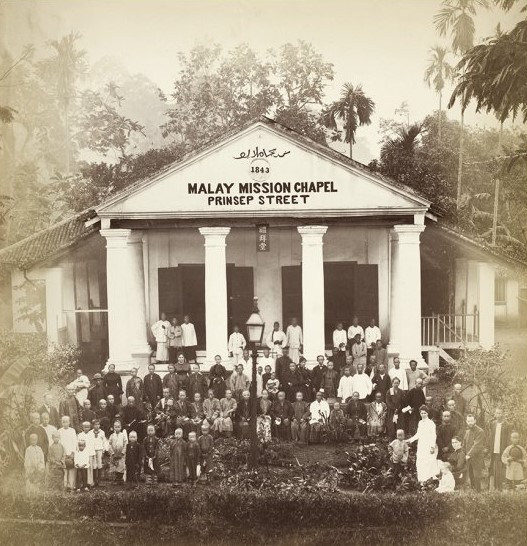

Keasberry started the Malay Mission Chapel in Prinsep Street, which came to be known affectionately as “Greja Keasberry“. It was the first church to conduct Malay services. The church building remains – it is now called the Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church.

Keasberry also started a school for Malay boys in 1848. Some of his students were from Malay royalty. The Temenggong Ibrahim of Johor, The Sultan of Muar and the Rajah of Kedah sent their sons to board at the school.

Keasberry died while preaching at the Malay Mission Chapel in 1875.

Local churches started to raise more local lay leaders who preached, evangelised and worked alongside the foreign missionaries.

Song Hoot Kiam was one who served faithfully at the Malay Chapel as treasurer and elder. He was also a community leader and his contribution to Singapore was recognised with the naming of Hoot Kiam Road.

Christianity began to be viewed, not as a foreign religion, but as one that locals could accept and identify with.

John Haffenden (1833-1913) (extreme right) was the first person appointed by the British and Foreign Bible Society to oversee the Bible Mission work in Singapore and Malaya. His appointment helped us become the centre of Scripture distribution where Bibles in almost 40 languages were sent out to other parts of the world. Photo, circa 1880s, courtesy of The Bible Society of Singapore.

China Inland Mission’s annual meeting (1906). For most missionaries in the early to mid-19th century, China was the real goal; many saw their stay in Singapore as a temporary sojourn. Picture, [Public Domain].

Wesley Methodist Church is the oldest Methodist church in Singapore. William Oldham was the first resident Methodist missionary. He also founded the Anglo Chinese School. ACS grew rapidly and by 1900 had the highest pupil enrolment. Picture of Wesley Church in an undated postcard, (Creative Commons).

Rev Benjamin Peach Keasberry (1811-1875) arrived in Singapore in 1837. For 38 years he served faithfully on our island and never left. He resigned from the London Missionary Society so that he could continue his work in Singapore as an independent missionary. Photo courtesy of Prinsep Street Presbyterian Church.

Although Keasbery‘s primary ministry was to the Malay-speaking locals, he was also concerned with the growing Chinese migrant population in the 1850s. Together with his Chinese colleague, Tan See Boo, Keasberry grew a Chinese-speaking church. Today, the Glory Presbyterian Church is the oldest Chinese-speaking church in Singapore. Photo courtesy of The Bible Society of Singapore.

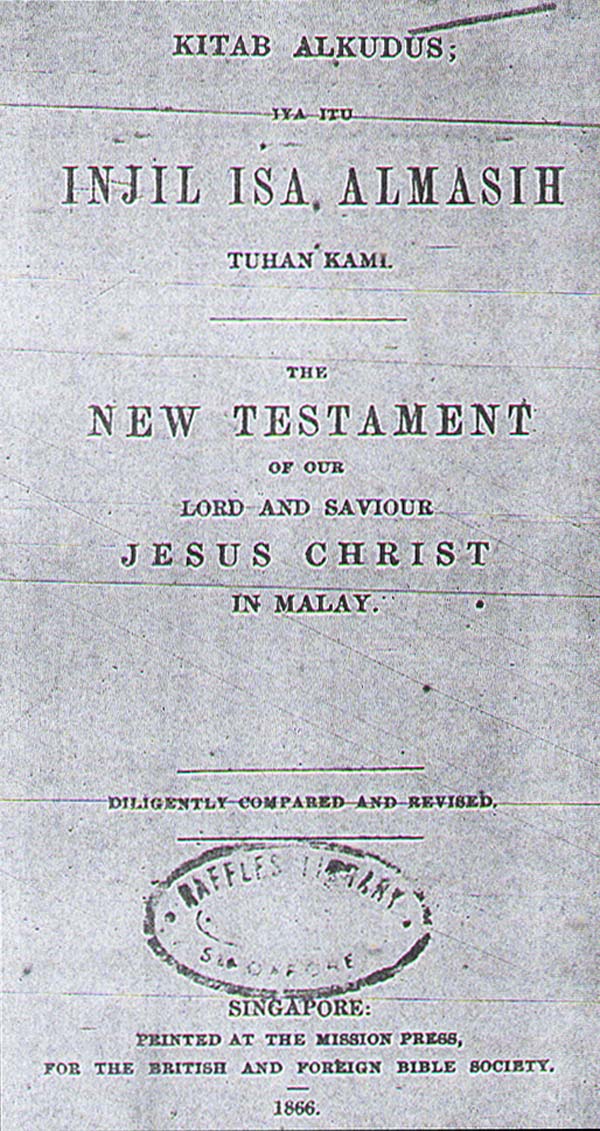

Keasberry printed and published the New Testament in Romanised Malay. It was a revision of an 1831 translation. This Bible remained popular among the locals and missionaries for over 40 years. Photo by Bob Kee (Creative Commons).

1913: Medical care becomes a priority

In 1913, the Anglican Church started its first women’s clinic in a shophouse. The colonial government provided an old school building in Cross Street to be used as a hospital for women and children.

In its early years, the St Andrew’s Mission Hospital treated only women and children. The founder of the Mission, Dr Charlotte Ferguson-Davie had observed that women did not seek treatment from male doctors. To reach out to them, the clinic had an all-female staff. Photo from https://www.samh.org.sg.

Today, St Andrew’s Mission Hospital remains a not-for-profit voluntary welfare organisation providing for the diverse needs of the local community.

The history of missionary medical care in Singapore continues in present-day hospitals and care facilities such as St Luke’s Hospital, Mt Alvernia Hospital, Assisi Hospice and St Joseph’s Home.

1930s: John Sung brings revival

In the 1930s, one man travelled to Singapore, and transformed the local church with powerful revival meetings.

He was John Sung, an evangelist from China.

For two weeks he preached – those of nominal faith were renewed with fervour while those hearing the Gospel message for the first time became believers.

By 1938, Christians represented an unprecedented 11.1% of the population.

Dr John Sung first visited Singapore in August 1935. He preached 40 messages over two weeks at Telok Ayer Methodist Church, with Miss Leona Wu interpreting. Ms Wu went on to establish Chin Lien Bible Seminary in order to continue training converts in Singapore. Photo from John Sung My Teacher, by Timothy Tow.

1942: Faith grows behind bars

During the Japanese Occupation between the years 1942 and 1945, church leaders of European descent were put behind bars.

Among them were the Anglican leader, Bishop Leonard Wilson, Archdeacon Graham White , Methodist pastors and Ernest Tipson of the Bible Society.

(In an intriguing turn of events, a Japanese officer would come to the rescue of church leaders and St Andrew’s Cathedral.)

Upon hearing news of the surrender on February 15, 1942, the Bishop of Singapore, John Leonard Wilson, proceeded to hold a service at St Andrew’s Cathedral. Despite the uncertainties that lay ahead, Bishop Wilson designed the Evensong Service for his congregation as one of praise and thanksgiving.

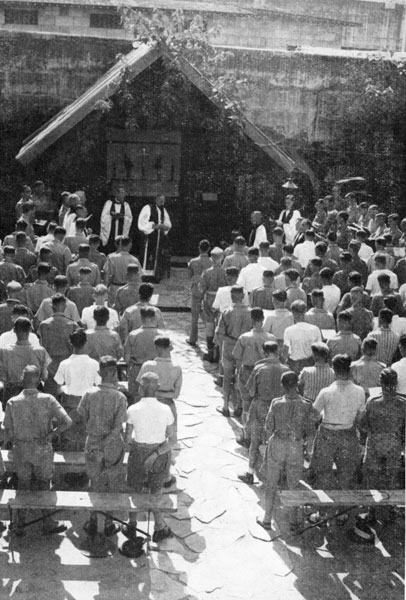

Church leaders who were interned now had a new flock to attend to – the prisoners-of-war.

In Bishop Wilson’s words, this particular service was one of the “most moving and impressive services he had ever attended”.

Church leaders who were later interned now had a new flock to attend to – the prisoners-of-war.

The weekly services in the prisons were packed out and prisoners by the thousands took Holy Communion together. Hundreds came to faith, finding solace in an overcrowded jail and strength in defeat.

Outside the prison walls, churches of the different denominations closed ranks and banded together to form the Federation of Christian Churches. Once a month they came together to worship at St Andrew’s Cathedral.

The war years served as a wake-up call for the mainline denomination churches. Even though many locals served as lay leaders, they lacked pastoral training.

The discussions among the interned church leaders in Changi Prison birthed the idea of a theological college to train the locals to serve the church.

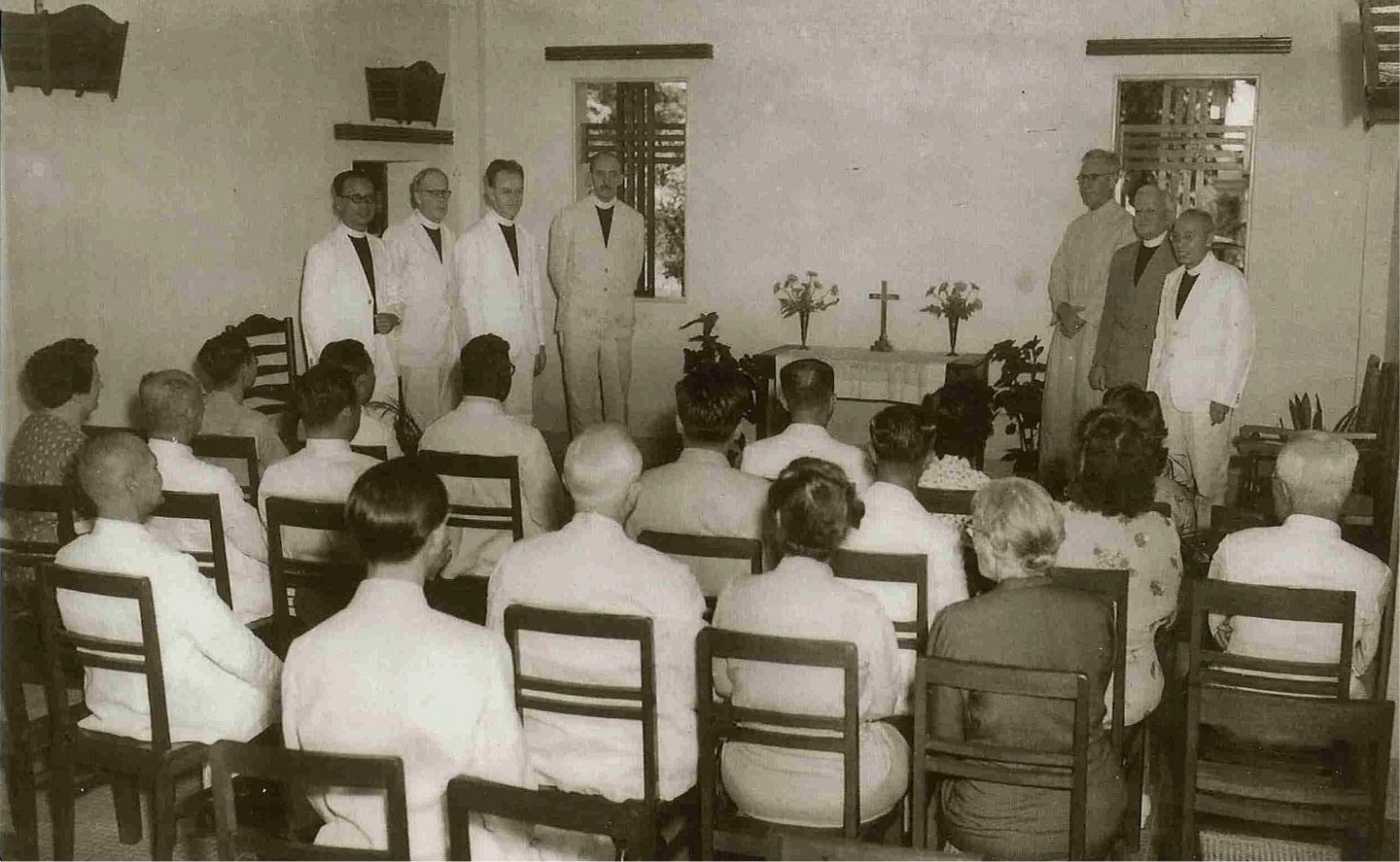

Three years after the War ended, Trinity Theological College was founded with support from the Methodist, Anglican and Presbyterian Churches.

Today Trinity Theological College continues to train and equip Christians for ministry.

The prisoners of war had to live in crowded cells and makeshift quarters in a central corridor. Picture from State Library Victoria [Public domain].

Confirmation Service in Changi Jail, September 7, 1945, with Bishop Leonard Wilson and Padre Eric Cordingly at the altar. Picture from The Changi Cross’ Facebook page.

St Andrew’s Cathedral was turned into an emergency hospital in the lead up to the British surrender. An aerial view of the cathedral taken by Fred Dunmore, 11 Squadron RAF, flying in a Bristol Blenheim in January 1940. Photo courtesy of St Andrew’s Cathedral and Richard Gilham.

The opening of Trinity Theological College (TTC), October 1948. The college is a collaborative effort among Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and Presbyterians. Photo courtesy of TTC.

Trinity Theological College’s first batch of graduates. There are now more than 1,800 TTC alumni active in various ministries in more than 49 countries around the globe. Photo courtesy of TTC.

1960s: Youth leaders rise up

By 1957, Singapore’s population had risen from under a million in 1947 to almost 1.5 million in a space of 10 years.

Unlike the generations before, for the first time most of the youths in the local population were born and bred in Singapore.

In 1957, 42% of the population were below 14 years of age. To meet the needs of the growing generation of young people, organisations such as Youth for Christ (YFC) were invited to Singapore.

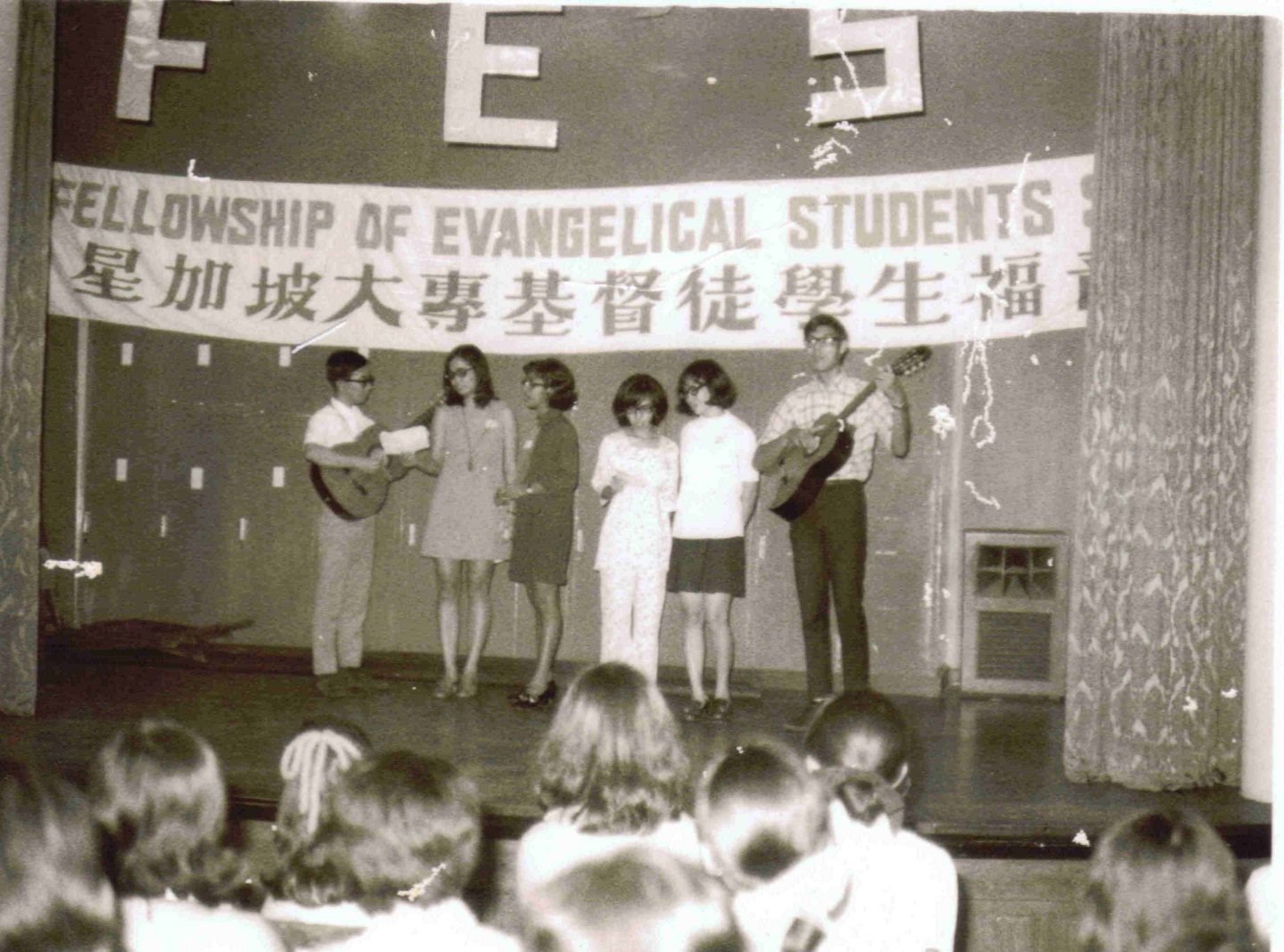

By the mid-60s, Youth For Christ and Inter-school Christian Fellowship were reaching about 2,500 students weekly through their activities.

On tertiary campuses, inter-denominational groups such as graduate Christian fellowships and inter-school Christian fellowships (ISCF) were formed.

By the mid-60s, YFC and ISCF were reaching about 2,500 students weekly through their activities.

On the church front, change was also in the air. Some congregations were beginning to witness the early signs of a Charismatic Movement.

The early 70s saw an outpouring of the Holy Spirit that swept through several mission and government schools along the Dunearn Road belt, as students gathered to pray and worship on their own.

Spiritual fervour took hold in what would be called the ACS (Anglo Chinese School) Clock Tower Revival.

That move gradually swept through the mainline Anglican and Methodist denominations, and left an indelible mark on the Singapore Church. While there were pockets of resistance, it also brought many believers together.

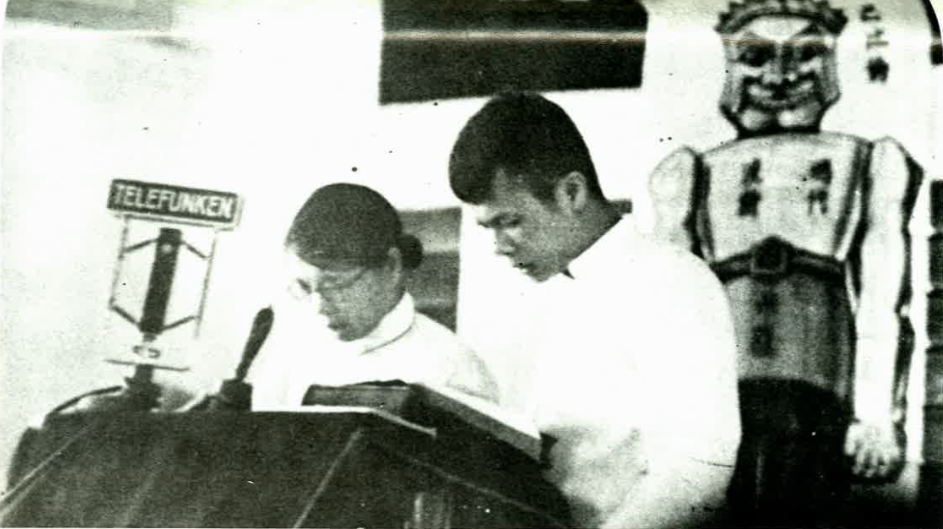

Varsity Christian Fellowship’s (VCF) annual conference at the former University of Malaya in Singapore, 1959. Photo courtesy of Fellowship of Evangelical Students.

A meeting at Nanyang University Christian Fellowship in the late 1960s. Photo courtesy of Fellowship of Evangelical Students.

In the early 70s, spiritual fervour took hold in what would be called the Clock Tower Revival. Salt&Light understands that, to this day, Anglo Chinese School tours for parents includes mention of the Clock Tower Revival.

1978: Dr Billy Graham comes to Singapore

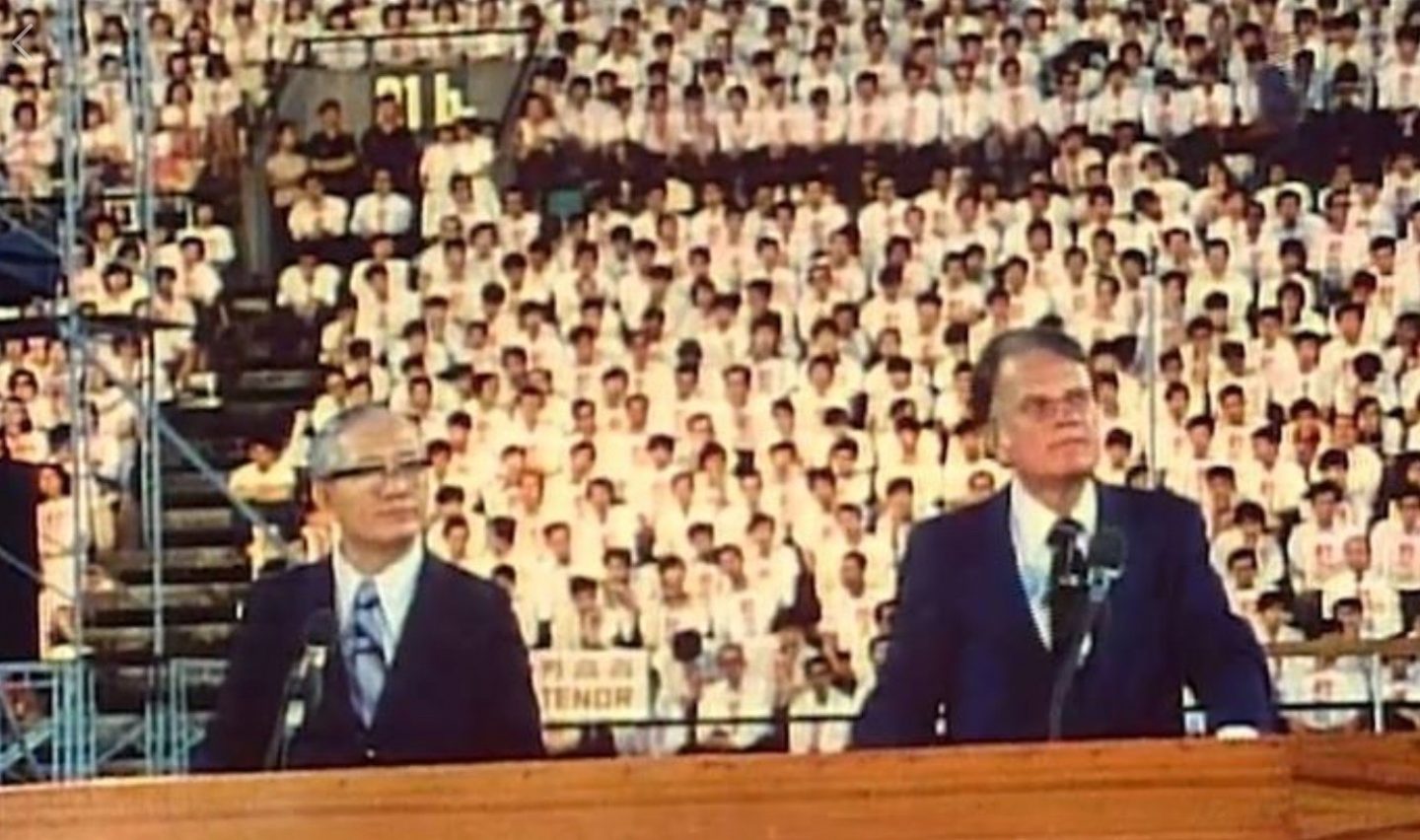

In 1978, more than 200 churches came together in unprecedented unity.

Evangelical churches from different denominations and para-church organisations worked together to organise the Bill Graham Crusade.

Even more astounding, 11,000 people made first-time decisions to follow Christ over the five evenings of rallies.

The renewed passion for God did not stop there but brought on the start of the church-growth era.

Calvary Charismatic Centre’s weekly congregation crossed the 2,000 mark to put it in the mega-church ranking.

Singapore is now home to several mega churches that surpass 10,000 in congregation.

Dr Graham with some members of the Singapore Billy Graham Crusade committee. Seated L-R: Dave Dawson (Asst Director for Counselling/Follow-up, Director of the Singapore Navigators), his wife Mary, Dr Benjamin Chew (Chairman of the executive committee), Dr Billy Graham, and Bishop Chiu Ban It (Chairman, Advisory Council). Standing: Dr Ernest Chew (Vice-Chair), Victor Koh (Chair, Operation Andrew), Rev Alfred Yeo (Gen Sec), Rev Dr Tony Chi (Chair, Ministers), Chan Chong Hiok (Campus Crusade), Prof Khoo Oon Teik (Vice-Chair), and Caleb Loo (Interpreter/Asst). Photo from The Navigators, Singapore.

The Singapore Billy Graham Crusade was held nightly from December 6-10, 1978.

Altar call at Singapore Billy Graham Crusade, 1978.

Calvary Charismatic Church in the 80s at the then New World Complex – a local church with a call to global missions. It is now called Victory Family Centre.

Now: Our story continues

In 1980, Christians constituted fewer than 10% of Singapore’s population. Today the number stands close to 20%.

At the three-day Celebration of Hope event at the Singapore National Stadium on May 17-19 this year, thousands convened to fulfil the Great Commission (Matthew 28:18-20).

In 200 years, we have gone from a colony waiting to receive missionaries, to a nation sending out missionaries.

Over three days and six rallies, more than 100,000 people heard testimonies and messages of God’s power and amazing grace in four languages.

Church congregations have also begun to look beyond their four walls, starting social enterprises and venturing further afield to be missionaries.

In 200 years, we have gone from a colony waiting to receive missionaries, to a nation sending out missionaries.

God continues to urge each of us to respond, to stand up and be counted as disciples of Singapore’s continuing Church history.

Tens of thousands gathered at the National Stadium on May 17-19 to hear God’s message in four languages – the first multi-language event of this scale. Photo by Joshua Pwee, Celebration of Hope.

Special thanks to Dr Ernest Chew, who kindly walked us through history. Dr Chew was on the faculty of the University of Singapore/NUS for 40 years, serving as Head of the History Department (1983-92), and Dean of Arts and Social Sciences (1991-97). He was also Chairman of the Oral History Advisory Committee and the Singapore History Museum. He currently serves as Vice Chairman of St Luke’s Hospital, and Vice-President of the Bible Society of Singapore.

Due to space constraints, Salt&Light is unable to include every milestone in Singapore’s Church history. If you have an interesting milestone or historical anecdote to share, please leave a comment below!

We are an independent, non-profit organisation that relies on the generosity of our readers, such as yourself, to continue serving the kingdom. Every dollar donated goes directly back into our editorial coverage.

Would you consider partnering with us in our kingdom work by supporting us financially, either as a one-off donation, or a recurring pledge?

Support Salt&Light